Jon Brooks • • 20 min read

George Orwell on the 7 Ways Politicians Abuse Language to Deceive You

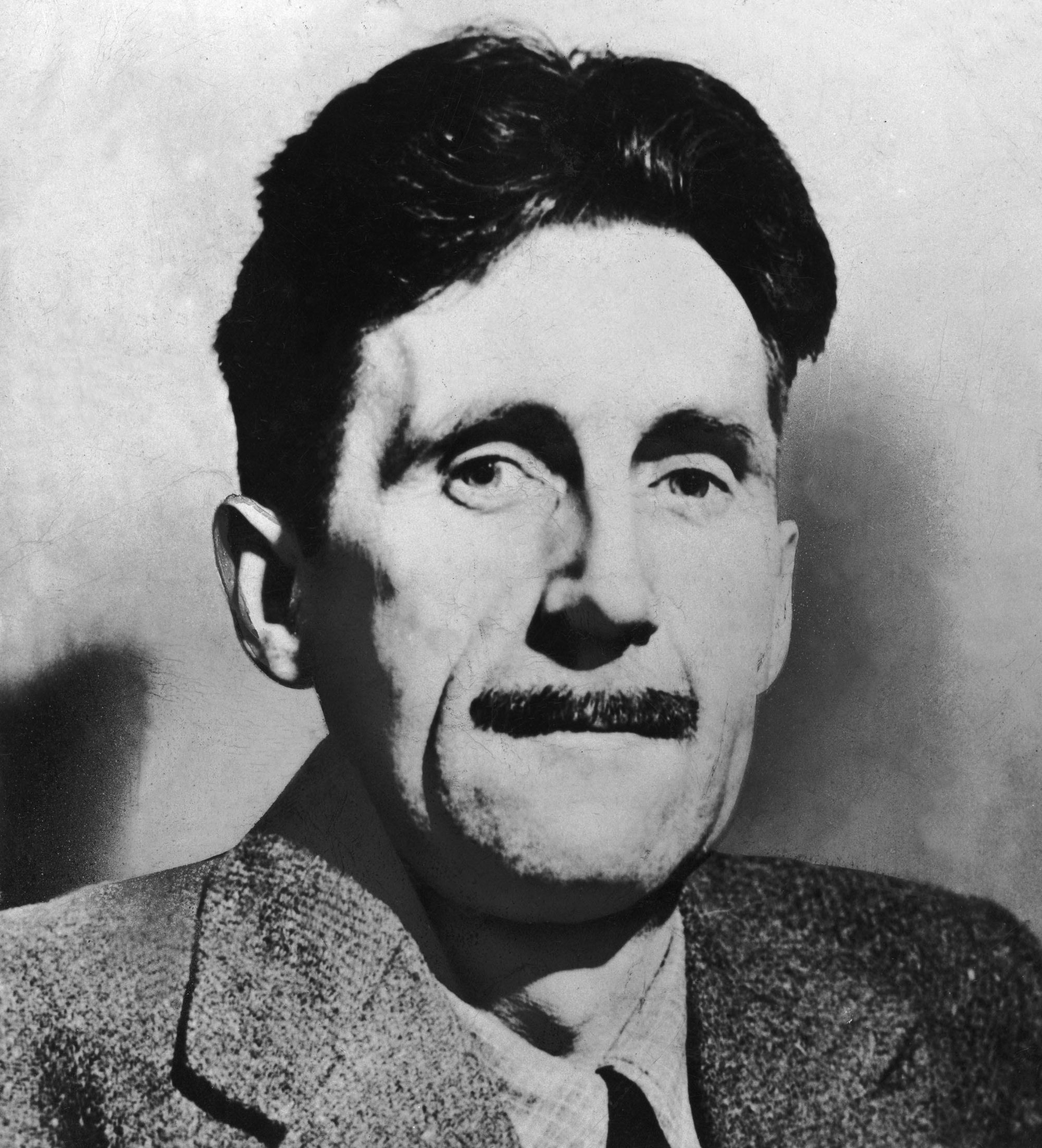

What words would you use to describe this face?

Take just a moment to really consider that question before moving on.

This is how the writer Christopher Hitchens interpreted the face1:

A slightly tall, angular, shy, but not unconfident Englishman, with a hollow-cheek look. A rather dolorous look in some ways, a rather solemn look. But yet it’s not the look of someone with no sense of humor. It’s the look of someone who’s been through quite a lot and has tried his best. But there is a final element of pessimism to it, as well as, I think, some of the hard-to-understand handsomeness for which we English people are so rightly famed. It’s an ironic look actually is what it is, and it’s the look of someone who suffered a great deal.

The man in the photograph, Eric Arthur Blair (1903 – 1950), was a novelist, essayist, journalist, critic, and, most importantly, an exemplary human being. He exited the womb English but entered the grave an outspoken citizen of Earth. Blair was born in Bengal, wrote his first articles in French, worked as a police officer in Burma, and settled in England. He is best known for his novels Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, both of which he wrote under a pen name with which you may be more familiar: George Orwell.

Orwell stands out from the other great writers of the 20th century because of his political awareness and opposition to totalitarianism, Stalinism, fascism, and social injustice. By concentrating on essays along with fiction, according to Hitchens, writing in Why Orwell Matters, Orwell was able to take on “the competing orthodoxies and despotisms of his day with little more than a battered typewriter and a stubborn personality.”2

But what makes Orwell stand out from the other great humanists of the 20th century, and why he should matter to you, is the way he took that stubborn personality of his and used it to tackle many of his own despotic and prejudicial inclinations. Hitchens expands:

The evidence of his upbringing and instincts is that he was a natural Tory [conservative] and even something of a misanthrope…3 He had to suppress his distrust and dislike of the poor, his revulsion from the ‘coloured’ masses who teemed throughout the empire, his suspicion of Jews, his awkwardness with women and his anti-intellectualism. By teaching himself in theory and practice, some of the teaching being rather pedantic, he became a great humanist.4

While Orwell’s writing often paints a hopeless picture of humanity, his self-taught humanitarianism proves that great change at the level of the individual is possible. His work cautions us about the seduction of selfishness, but his life shows us that compassion is not inherited—it’s cultivated.

Orwell wasn’t just a critic of his times: he is a critic for all times. Even now, sixty-five years after his death, his work seems just as, if not more, relevant. The following list provides some insight into the prophetic themes of Orwell’s work:

- His work on the conflict between regional nationalism and European integration.

- His social investigations, which helped lay the ground for what we now call “cultural studies.”

- His fascination with the problem of objective or verifiable truth, which he feared was being driven out of the world by the deliberate distortion and even obliteration of recent history.

- His love for “growing things” and concern with the future of the natural environment or what is now considered as “green” or “ecological.”

- His acute awareness of the dangers of “nuclearism” and the nuclear state.

- His views on the English language, and his urge to defend it from the constant encroachments of propaganda and euphemism. 5

All those themes are somewhat related, but in this article I’ll be focusing on the last listed item: Orwell’s views on language and its corrosive influence on the individual and the state. To do this, I will draw from Orwell’s essay On Politics and the English Language7.

With Orwell’s guidance, I will show you how politicians distort facts and deceive listeners with their word choices, how our constant exposure to political speech dulls our sensory acuity, and how learning to write well (a subject on which Orwell will soon instruct us) is the best practice for thinking well, and, ultimately, reforming the world.

Orwell’s main argument in Politics and the English Language is that language and thought act much like conjoined twins of the human psyche, and thus, “If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” If we disregard the health of one twin, we encumber the other. Orwell goes on to explain:

Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration…

Is the President a Puppet?

I don’t believe in the Illuminati, but I can see why one would. When a high-ranking politician delivers a speech, it can seem as though they’re merely a puppet, a tool, acting as a chess piece in a much larger maneuver, in a much larger game, in which, like us listeners, they are the played and not the player.

Orwell describes this effect in his essay:

When one watches some tired hack on the platform mechanically repeating the familiar phrases — bestial, atrocities, iron heel, bloodstained tyranny, free peoples of the world, stand shoulder to shoulder — one often has a curious feeling that one is not watching a live human being but some kind of dummy: a feeling which suddenly becomes stronger at moments when the light catches the speaker’s spectacles and turns them into blank discs which seem to have no eyes behind them.

And this is not altogether fanciful. A speaker who uses that kind of phraseology has gone some distance toward turning himself into a machine. The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved, as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. If the speech he is making is one that he is accustomed to make over and over again, he may be almost unconscious of what he is saying, as one is when one utters the responses in church. And this reduced state of consciousness, if not indispensable, is at any rate favourable to political conformity.

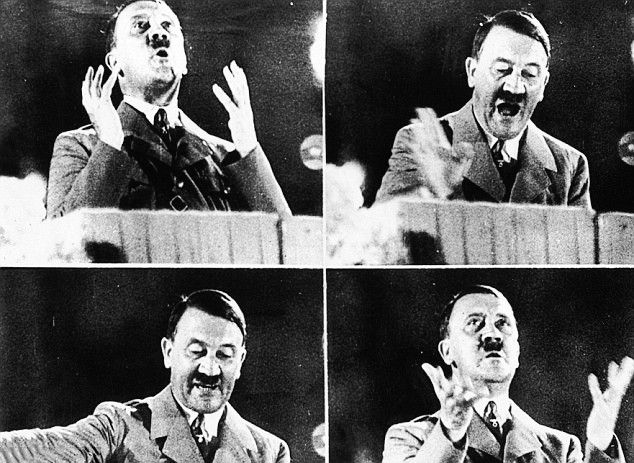

Emotional states are contagious. Charismatic speakers like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Adolf Hitler were able to move the masses by kindling the passion they wanted their listeners to feel but in themselves first.

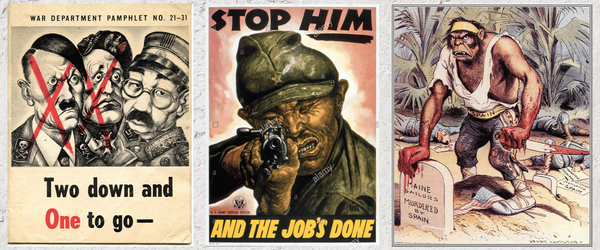

Hitler had a knack for turning placid crowds into mouth-foaming mobs.

From this perspective then, it makes sense that a politician who wants to do the opposite—who seeks to elicit unthinking conformity from his audience—would make himself mindless by mindlessly reciting words that were written for him and not by him.

Thinking with Sober Clarity

A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.

If we all took great pains to improve our writing by questioning the deeper meaning of stock phrases like “took great pains,” if we all revelled in the delicious difference between “disinterested” and “uninterested,” if we were as quick to put our ear to the ground of linguistic trends as we are the latest Twitter trends, if we learned how to write active prose but also understood how passive prose was written, if we could pique our own passion for writing and take that first step towards the peak of political reform, we could peek a new world: a world where the power has been plucked from the palms of the perverted, propaganda-puppets we call politicians and returned to the people—the ordinary people.

[T]he fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers…In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics’. All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred, and schizophrenia. When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer.

Standing shoulder to shoulder as comrades in clear thinking, we could create not an Orwellian army, but an army of Orwells to take on the competing “orthodoxies and despotisms” of our day. Orwell had one battered typewriter and one stubborn personality—between us, we have billions.

But you don’t have to do this. As Orwell makes clear in his essay:

[Y]ou are not obliged to go to all this trouble. You can shirk it by simply throwing your mind open and letting the ready-made phrases come crowding in.

If you’re just as fine living by the cliché “ignorance is bliss” as you are writing it without a second thought, I must caution you: after reading the seven ideas that follow, you’ll never be able to view politics and the media the same way again.

George Orwell’s 7 Most Common Problems with Language

Are you sure you’re not a writer?

To reemphasize Orwell: clear writing and clear thinking are not just the “concern of professional writers.” We are all writers and critics in some capacity. It doesn’t matter if you’re a published author, a blogger, a social media enthusiast, a private journaler like Anne Frank, or merely a concerned citizen. Your words and your thoughts matter, but they matter so much more when they truly belong to you.

Orwell says that if you let them, politicians “will construct your sentences for you—even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent—and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself.” The following seven concepts will prevent this from happening to you.

1. Clichés & Dying Metaphors

By using stale metaphors, similes, and idioms, you save much mental effort, at the cost of leaving your meaning vague, not only for your reader but for yourself.

Politicians love using clichés. In the Guardian article Politicians’ favourite clichés revealed, we find a study—of sorts—carried out by a John Hardy Clarke. During the four-month run-up to a 2001 British election, Clarke counted and sorted all the clichés that were said on political broadcasts. At the top of the list was “the fact of the matter is”, which was said 740 times. Second was “and again, if I can just make this point”, which was uttered 430 times. Lastly, “there is no instant solution” was repeated 412 times.

Here are the twelve most popular political clichés Clarke found:

- The fact of the matter is…

- And again, if I can just make this point…

- There is no instant solution…

- It’s going to take time…

- A whole range of proposals…

- There are no easy answers…

- We want to see a wide range of options right across the board…

- That is why we’re putting in more money in real terms than any previous administration…

- Looking at a comprehensive draft of measures…

- The dire situation we inherited from the previous administration…

- Let me at this stage be absolutely open and honest…

- Our message is very clear and very simple…

The fact of the matter is, these clichés sometimes act as filler, allowing politicians to respond to a question for which there are no easy answers or instant solutions. These vacuous phrases can also create the illusion of an answer since a sound is coming out of the speaker’s larynx, but the meaning is neither very clear nor very simple. As they feed you their draft of measures, you might ponder the whole range of their proposals, or, if you’re like me, feel annoyed by their dire set of rhetorical devices they inherited from the previous administration. But again, if I can just make this point: never mimic the style of this paragraph in your spoken or written language. Condemn vagueness and kill cliché, especially in matters that concern your country.

Clichés come in many forms. In fact, any phrase that “betrays a lack of original thought” is a cliché. Orwell particularly disapproved of a type of cliché he called “dying metaphors”:

A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image, while on the other hand a metaphor which is technically ‘dead’ (e. g. iron resolution) has in effect reverted to being an ordinary word and can generally be used without loss of vividness. But in between these two classes there is a huge dump of worn-out metaphors which have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves.

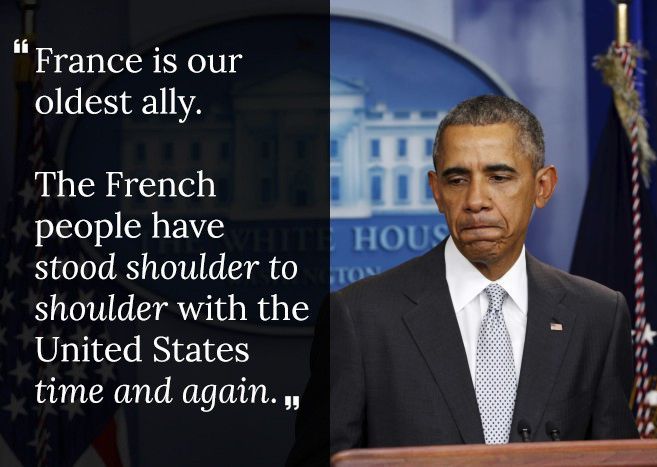

Orwell lists the following as examples: Ring the changes on, take up the cudgel for, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, play into the hands of, no axe to grind, grist to the mill, fishing in troubled waters, on the order of the day, Achilles’ heel, swan song, hotbed.

For a recent example of the use of cliché in politics, I’ll refer you to President Obama’s November 15, 2015, statement on the terrorist attacks in Paris, in which he said:

Good writers tend to describe the familiar in a way that sounds unfamiliar and the unfamiliar in a way that feels familiar. Not-so-good writers describe the familiar in familiar terms, making the imagery stale and mundane, and describe the unfamiliar in unfamiliar terms, making it indecipherable for the layperson. The problem with the former over-familiar, cliché-prone way of describing things, according to Alain de Botton in How Proust Can Change Your Life, “is not that they contain false ideas, but rather that they are superficial articulations of very good ones…Clichés are detrimental in so far as they inspire us to believe that they adequately describe a situation while merely grazing at its surface.”8

Marcel Proust was a master of writing original images. A friend of Proust’s once tried his hand at writing a novel. He asked Proust for some feedback. In his lengthy, balanced review, Proust kindly disparaged his friend’s use of dying metaphors:

There are some fine big landscapes in your novel, but at times one would like them to be painted with more originality. It’s quite true that the sky is on fire at sunset, but it’s been said too often, and the moon that shines discreetly is a trifle dull.

Eight years later, Marcel Proust wrote his own description of a moon:

Sometimes in the afternoon sky a white moon would creep up like a little cloud, furtive, without display, suggesting an actress who does not have to ‘come on’ for a while, and so goes ‘in front’ in her ordinary clothes to watch the rest of the company for a moment, but keeps in the background, not wishing to attract attention to herself.9

If you want to elevate your descriptive writing to Proust’s level, you must turn your words into a lens through which the reader can experience the world with “new eyes.”

How exactly do you do that?

Here are Orwell’s four questions to ask yourself when you next review your written imagery:

- What am I trying to say?

- What words will express it?

- What image or idiom will make it clearer?

- Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?

2. Wordiness

The second failing of political speech Orwell addresses in Politics and the English Language is wordiness. Back home, whenever my father asks me a direct question, and I answer in a long-winded, vague way, I’ll often get the response, “Are you a politician or what?” It always makes me chuckle—with recognition.

Politicians speak in such a way that seems precise and intelligent, but if you carefully scrutinize their language, you’ll see that the nature of their sentences are actually completely full of unnecessary words. So, the next time you hear the sound of a politician talking about how our nation has learned from past history, and how the major political breakthroughs of the 21st century will help us, the people, to unite together and reconsider again just how lucky we are to be alive today, you may have the unexpected surprise that roughly 19% of their words are pointless.10

3. Passive Voice

If the subject performs the action of the verb, we call that active; if the subject receives the action, we call that passive. Politicians often use the passive voice when they want to dodge responsibility. The classic example being:

Active voice: I made a mistake.

Passive voice: Mistakes were made.

While searching online for examples of the passive voice, I stumbled upon a 1974 speech by the soon-to-be 39th American President, Jimmy Carter, which perfectly displays the devious power of the passive voice. Here’s what was said:

I’ve had a constant learning process, sometimes from lawyers, sometimes from practical experience, sometimes from failures and mistakes that have been pointed out to me after they were made.

Notice how Carter frames himself as the receiver of the action. He’s also careful to list his “practical experience” separately from the author-less “mistakes”. Who exactly has made the mistakes Carter is alluding to? Him? His staff? Us?

I rewrote the statement in an active, direct voice for comparison. Here, Carter drives the action:

I am constantly learning. Sometimes I learn from lawyers, and sometimes I learn from practical experience, including my failures and mistakes.

Now that’s a statement I can respect.

I found another example of the passive voice being used in politics that was too terrible to omit. The paragon of articulation himself, George W. Bush Jr., in his Address to the Nation on the Troop Surge in Iraq, stated:

The situation in Iraq is unacceptable to the American people – and it is unacceptable to me. Our troops in Iraq have fought bravely. They have done everything we have asked them to do. Where mistakes have been made, the responsibility rests with me.

These three sentences are everything wrong with political language. First, the unacceptable cause of “the situation in Iraq” is unclear. Is George saying that the US invaded because of the unacceptable situation in Iraq, or that the result of the invasion is unacceptable? The final sentence: “Where mistakes have been made, the responsibility rests with me” is exactly the type of ambiguous atrocity Orwell admonished. Even the connotatively-loaded word “rest” seems forced in to produce a resolute and peaceful climax, but that topic deserves a section unto itself.

4. Sentences Saved from Anticlimax

Leaders need to exhibit certainty. In times of political chaos—which is more or less all the time—we crave the solution, not a solution. For politicians to be voted into office, they need to appear as though they have all the answers, even when they don’t. “I’m sorry, I am unsure” is a perfectly good response to a question about the future of world affairs, but one that you will never hear from a politician.

A common technique politicians use to maintain their steadfast authority, is to end their sentences with an emphatic, everything-will-be-alright sense of assuredness. It seems a strong ending to a weak answer goes a long way.

Here’s an extract from Obama’s speech in the Post Iran Nuclear Accord Announcement Press Conference. I’ve emboldened the ends of his sentences to reveal his virtuoso ability to save sentences from anti-climax:

And as I said yesterday, the details of this deal matter very much. That’s why our team worked so hard for so long to get the details right. At the same time, as this debate unfolds, I hope we don’t lose sight of the larger picture – the opportunity that this agreement represents. As we go forward, it’s important for everybody to remember the alternative and the fundamental choice that this moment represents.

Being aware of emphatic word order may make your writing stronger. It’s actually a handy rhetorical device. Let’s just be careful not to confuse style with substance. The difference between the two, I think you’ll agree, matters very much.

5. Pretentious Diction

In 2013, a paper was published called The Seductive Allure of “Seductive Allure” which highlighted our over-trust in complex-seeming neuroscience explanations—even when they’re circular and illogical11. Acclaimed neuroscience author Steven Pinker said of this phenomenon something that applies just as well to Orwell’s view on political language:

[Some scholars] spout obscure verbiage to hide the fact that they have nothing to say. They dress up the trivial and obvious with the trappings of scientific sophistication, hoping to bamboozle their audiences with highfalutin gobbledygook.

I don’t always find the use of big words invidious. Sometimes their use can be chrysostomatic—pulchritudinous even. But it’s a mistake to assume that all quotidian sentences, by implication, are jejune. On the whole, I consider myself fairly eleemosynary in judging other people’s writing. I may put up with a mélange of pompous words and brush off the author’s intentions as jocose, as I’m sure you will with mine. The problem with pretentious diction only becomes axiomatic when the topic is serious—say, for example, the governance of a country. When hearing pretentious diction keep in mind that the espouser of such verbosity may have just looked up a bunch of highfalutin words on Google, which they don’t really understand, to appear intelligent. That’s what I did.

This is Orwell’s list of pretentious words commonly used in politics:

Words to dress up simple statements and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgements: phenomenon, element, individual (as noun), objective, categorical, effective, virtual, basic, primary, promote, constitute, exhibit, exploit, utilize, eliminate, liquidate.

Adjectives to dignify sordid processes of international politics: epoch-making, epic, historic, unforgettable, triumphant, age-old, inevitable, inexorable, veritable.

Words included in the attempt of glorifying war: realm, throne, chariot, mailed fist, trident, sword, shield, buckler, banner, jackboot, clarion.

6. Words with Variable Meanings

When politicians repeatedly spout buzzwords at us, or as Orwell called them, “meaningless words,” it doesn’t take long before we start to accept them as part of the linguistic furniture—their usage becomes unquestioned, and so does their meaning.

“The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’,” writes Orwell. And, “In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning.”

In 1948, two years after On Politics and the English Language was published, Eleanor Roosevelt made a speech in Paris where she discussed The Struggle for Human Rights. Her speech seems heavily influenced by Orwell’s essay12, but, ironically, as you’ll see, it is also the a violator of its own moral:

We must not be deluded by the efforts of the forces of reaction to prostitute the great words of our free tradition and thereby to confuse the struggle. Democracy, freedom, human rights have come to have a definite meaning to the people of the world which we must not allow any nation to so change that they are made synonymous with suppression and dictatorship.

There are basic differences that show up even in the use of words between a democratic and a totalitarian country. For instance “democracy” means one thing to the U.S.S.R. and another the U.S.A. and, I know, in France.

Orwell marks these words as being too variable to mean anything concrete: democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice, class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality, romantic, plastic, values, human, dead, sentimental, natural, vitality.

George Orwell also despised the use of the “not un- formation” in political language, going so far as to say that it would be possible, even, to “laugh the not un- formation out of existence.”

To achieve this, he encourages us to memorize the sentence:

A not unblack dog was chasing a not unsmall rabbit across a not ungreen field.

7. Oversimplification

Reverend Dr. Giles Fraser, who lectures on morality and ethics at the Academy of the British Ministry of Defence, says that “killing in combat for a psychologically normal individual is bearable only if he or she is able to distance themselves from their own actions.”

One such way the military helps their soldiers get over that reluctance to kill is by giving them a new vocabulary which reframes horrific acts of brutality as mere strategy. Human enemies that need to be murdered become “targets” to be “reduced”.

In a telling interview by the BBC on this topic, Lt Col Pete Kilner said:

We talk about destroying, engaging, dropping, bagging – you don’t hear the word killing.

Orwell referred to this dehumanizing, oversimplification of language as, “the defense of the indefensible.”

He goes on:

[T]he atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.

Orwell lists these three examples of oversimplification in political language along with what they really mean if one were to unpack them:

Pacification = Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets.

Transfer of population = Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry.

Elimination of unreliable elements = People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps.

The Problem with Politics and the English Language

When it comes down to it, good writing and thinking is not about having perfect grammar or impeccable punctuation. “What is above all needed,” Orwell writes, “is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around.” The worst thing we could do is “surrender” to words.

I sincerely hope that this article has given you some insight into why the meaning-choosing-the-word approach is so important and how you can start using it in your writing. To finish, I’ll leave you with what Orwell considered to be the root cause for bad writing and with it, the best solution.

The problem:

When you think of a concrete object, you think wordlessly, and then, if you want to describe the thing you have been visualising you probably hunt about until you find the exact words that seem to fit it. When you think of something abstract you are more inclined to use words from the start, and unless you make a conscious effort to prevent it, the existing dialect will come rushing in and do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning.

The solution:

Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations. Afterward one can choose — not simply accept — the phrases that will best cover the meaning, and then switch round and decide what impressions one’s words are likely to make on another person.

George Orwell’s 6 “Rules” for Better Writing and Better Thinking

1) Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

2) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

3) If it is possible to cut a word, always cut it out.

4) Never use the passive where you can use the active voice.

5) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

6) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

A Final Message From George Orwell

Political language — and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists — is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. One cannot change this all in a moment, but one can at least change one’s own habits, and from time to time one can even, if one jeers loudly enough, send some worn-out and useless phrase — some jackboot, Achilles’ heel, hotbed, melting pot, acid test, veritable inferno, or other lump of verbal refuse — into the dustbin where it belongs.

And if you found this article helpful or important at all, please pass it along to your friends.

- Hitchens, Christopher. “Christopher Hitchens ~2005 – Why Orwell Matters.” YouTube. YouTube, 21 Oct. 2002. Web. 17 Nov. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rY5Ste5xRAA. ↩︎

- Hitchens, Christopher. “Introduction.” Why Orwell Matters. New York: Basic, 2002. 26. Print. ↩︎

- Hitchens ↩︎

- Hitchens, Christopher. “Introduction.” Why Orwell Matters. New York: Basic, 2002. 27. Print. ↩︎

- Hitchens, Christopher. “Christopher Hitchens on George Orwell’s Political Mind.” Vanity Fair. 1 Aug. 2012. Web. 17 Nov. 2015. http://www.vanityfair.com/unchanged/2012/08/christopher-hitchens-george-orwell. ↩︎

- Hitchens, Christopher. “Introduction.” Why Orwell Matters. New York: Basic, 2002. 29. Print. ↩︎

- Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” Resort. 1946. Web. 17 Nov. 2015. http://www.resort.com/~prime8/Orwell/patee.html. ↩︎

- Botton, Alain. “How to Express Your Emotions.” How Proust Can Change Your Life. New York: Pantheon, 1997. 124. Print. ↩︎

- Botton, Alain. “How to Express Your Emotions.” How Proust Can Change Your Life. New York: Pantheon, 1997. 123–125. Print. ↩︎

- There are 98 words in this paragraph, and 19 are crossed out, giving the word redundancy percentage of 18.62%. ↩︎

- Farah, M. J., and C. J. Hook. “The Seductive Allure of ”Seductive Allure”” Perspectives on Psychological Science (2013): 88–90. Print. ↩︎

- I can’t verify that Eleanor Roosevelt had read On Politics and the English Language, but we do know that she was a fan of Orwell because writing in her popular column My Day in 1951, she said that she had recently read Animal Farm and “enjoyed every word.” ↩︎

Jon Brooks

Jon Brooks is a Stoicism teacher and, crucially, practitioner. His Stoic meditations have accumulated thousands of listens, and he has created his own Stoic training program for modern-day Stoics.