Nat Dollin • • 18 min read

12 Life Lessons Learned While Living in a Van and Traveling Europe

Is anyone tired of reading stories about #vanlife and how unfathomably cool and liberating it is living life “on the road?”

How exuberant, how effortless these bloggers’ lives seem to be; always amidst some stunning landscape, with an equally stunning significant other languorously draped over a surfboard, brewing coffee, smoking mussels over an open fire, watching the sun rise and set, gazing at the stars without a care in the world…

I will admit (rather sheepishly) that I used to scour these types of blogs with a mixture of chagrin and wide-eyed enthusiasm. And although the triggers may differ between individuals, I think at some point or another most of us can relate to feeling simultaneously inspired and antagonized; intrigued, yet oddly ruffled.

The allure of the open road doesn’t require too much explanation here, but I think the vexation deserves some reflection. What is it about online, shareable media that has the propensity to enable an instantaneous feeling of lack in our own lives? Is it that we truly wish we were somewhere else, or doing something else at this very moment? Are we frustrated with ourselves for not yet having taken the strides to move towards our dreams? Or, are we arousing needless confusion because the truth is, we are genuinely content with our current situation, but what we’re browsing makes us question the validity of our satisfaction?

I can’t help but recall what Jack Kerouac wrote (appropriately and coincidentally) in On The Road:

“I realized these were all the snapshots which our children would look at someday with wonder, thinking their parents had lived smooth, well-ordered lives and got up in the morning to walk proudly on the sidewalks of life, never dreaming the raggedy madness and riot of our actual lives, our actual night, the hell of it”

— Jack Kerouac

Although young Kerouac was not referencing Tumblr or Instagram at the time, the message remains startlingly relevant: one photo, however captivating, is never the whole story.

I think by now, there is a hearty worldwide conversation in session about the lavishly filtered nature of social media, and the damaging effects it can have on our sense of self and our perspective of reality. Many of us are aware that what is shared online is often an edited version of the poster’s interpretation of truth, and we can use this knowledge to rationally supersede any incoming distress.

However, if when browsing we experience even a flash of that inner conflict—simultaneously inspired and antagonized—it becomes clear that there is a leak in our cognitive feedback loop, and that rational dialogue has not yet fully infiltrated our emotionally-driven response mechanisms. The truth is that we know there must be more to the story than what we’re receiving, but as Kerouac illustrates, it’s far easier to get caught up in the wonder of a snapshot than to consider all the raggedy details that contributed to its making.

And so you can probably imagine, when I was approached to write about my own experiences of living and traveling in a van, there was a natural hesitation in my response. A flood of doubts: Isn’t the internet already saturated with this topic? Won’t it be hypocritical of me to contribute to a pool of representation that I feel is at least partially responsible for our comparison complexes? What can I possibly bring to the table?

That last question helped a lot to refine my motivation. Because now that it’s all down on paper, I see that none of these lessons are confined to being learned or carried out on the road. In fact, the way they permeate my home life is more recognizable than their moment of insertion into my psyche whilst traveling in a van. And what I’d like to share with you today is not so much my experience of van life or the allure of the open road, but more what I actually learned from the experience and how it transmutes into #non-vanlife.

What I Learned from Remodeling, Traveling and Living in A Van

1/ You are capable of more than you think.

(Apologies for beginning with a platitude, but this one is absolutely true!)

Anyone who knows me will tell you that I knew nothing about automobiles. I knew you had to put gas in them on a regular basis and I would nod and smile when people spoke of carburetors. But I had never owned a vehicle prior to my first van purchase and that made acquiring (let alone driving) one quite a risky process. I had no idea what questions to ask a seller, and I couldn’t tell the difference between “normal” required maintenance and “seriously dangerous” mechanical faults. I sought out seasoned advice from a few local garages to help me on my quest, but the cynicism with which my inquiries were met damn near extinguished my zeal for the project. (There is certainly a sub-lesson here: choose wisely who you seek advice from, or if you even need advice in order to move forward.)

I could write at length about how ill-prepared I may have seemed for such a venture, but I think you get the gist. The important part is that I did it. I found a van that suited me, I rebuilt it the way I wanted to, and shortly thereafter drove it around Western Europe for around eight months, pretty much without issue. I’m sure I surprised a few friends and family, but moreover I surprised myself.

Don’t let your current self stop you from becoming your future self. If you’ve got a dream, take a tip from Nike…

Just Do It!

2/ Being able to touch and use things that you’ve crafted with your own hands on a daily basis feeds your soul in immeasurable ways.

I can’t stress this one enough. I feel as though the majority of products I engage with in daily life have been made by someone (or something) else. This proliferates my sense of disconnection from what I’m doing and how I’m doing it. But when I do something myself—whether it’s plucking homegrown radishes from the soil, hand-binding a new journal or re-painting my skateboard—I derive so much pleasure not only from the process itself, but further from the satisfaction in the subsequent use (or digestion) of those creations.

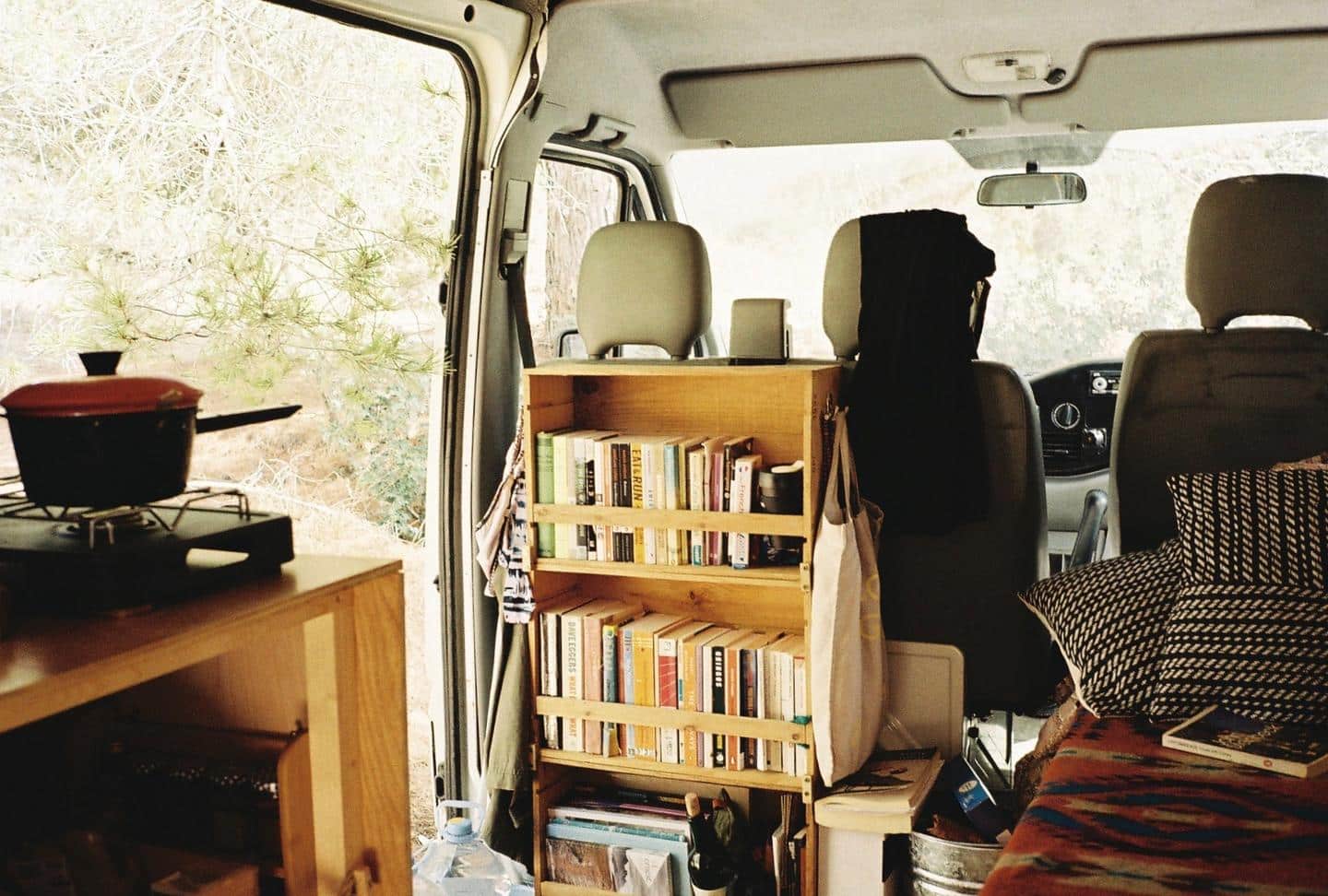

Constructing a comfortable living space in the back of a van with an assortment of woodwork, ceramic and fabric enhanced my enjoyment of even the simplest of activities. I sleep better on the mattress cover that I stitched myself, I revel in the process of plucking a book from the shelving that I constructed, and I appreciate the smooth surface of wood that I varnished.

I also value my relationships with those who helped me to manifest this particular dream. It would have likely not come to fruition (at least not so smoothly) without the volunteered help from friends, most of whom I hadn’t actually seen in well over a year. On top of the fact that I had no mechanical knowledge of my new vehicle, I had also never done any carpentry, but decided that I wanted to remodel the living area of the van from scratch. Accepting that I couldn’t (and didn’t need to) manage everything alone was the catalyst for reconnecting with solid friends, and getting our hands dirty together was such a heartwarming and invigorating experience—it made me wonder why we don’t do things like that more often?

Their involvement also contributes to my enjoyment of van use: I see the floor panels they nailed, the holes they drilled, and the latches they carved by hand, and I’m reminded of how fortunate I am to have these people in my life and how goddamn cool it is that we got to spend part of the summer on my parents’ driveway all covered in sawdust.

3/ Organization is essential.

A van provides a nice middle ground: it’s not as small as a backpack, but it’s not as large as a house. This means that you can bring some extra luxuries without having to worry about weight, but at the same time remain conscious about what you really want to have at your fingertips.

When your living space becomes limited, getting organized suddenly gains importance. Leaving anything lying around (like wet towels, half-read books or dirty dishes) is simply not an option, especially if you’re about to drive off somewhere. Much like a boat, everything must be secure and stowed for travel, otherwise you’re likely to cause major damage and distraction once driving.

Having to organize and clean house at regular intervals proved to have calming side effects: I found that I engaged more with activities as I did them (which leads me to point #4 of radically simplifying) and enjoyed completing them by continually returning everything to its right place after use. As a result, even since moving into an apartment, I now find that I fold my clothes away as soon as I’m done wearing them, sweep or vacuum when I can see it’s necessary, and do small stints of washing up throughout the day so it never becomes a chore. Some readers may naturally behave this way already, but it had to become a necessity for me before I realized how much easier life is when we’re organized!

4/ There exists always the option to radically simplify one’s daily activities.

In a previous article, I quoted Sylvain Tesson’s thoughts regarding life on retreat:

“By restricting the panoply of actions, one goes deeper into each experience. […] Existence becomes reduced to a dozen or so activities.”

Sometimes limitations help to create fuller experiences, and this rings true when living in a van. Because there is a limit to what one can do, each activity—however minute—becomes slower, more pensive, and more significant in its own right. Even making a cup of tea (and drinking it) becomes a lengthy process; poetically ritualistic. Because everything requires effort, and spacial awareness, nothing is done for the sake of it. This prompted me to reconsider what is really necessary in my home routine, and how I could simplify my day by cutting activities that really weren’t missed when living in the van.

If my correspondents could accept delayed replies to emails when I was on the road, why would they feel any different now that I’m living at home? If I could eat happily for days with one small box of groceries, why would I need to continually keep a fridge stocked to the max? If I could clean up and get dressed with no reflection of my appearance, why would I need a mirror to decipher whether or not I am fit to leave the house?

Which leads me to my next point…

5/ Mirrors for the purpose of vanity are a waste of time. (Mirrors for driving are an excellent idea though.)

Okay okay. I can sense the rebukes! Gents—if you need to shave, I get it.

The idea here is not to demonize use of mirrors, but to bolster an awareness for how we’re using them and for how much time. Living without access to my own reflection emboldened me to feel my appearance, rather than see it. I would still take care to wash my face in the morning, brush my teeth, and choose an appropriate outfit, but my judgement of how I was presenting myself rested on the care with which I had enacted the above processes. It wasn’t until stumbling upon a mirror in a friend’s house that I realized it had been weeks since I last saw what I looked like, and I hadn’t missed it. With reduced preoccupation for my physical appearance, I was free to witness more fully what was happening around me in the day at hand.

6/ Nature can be just as entertaining, if not more so, than digital entertainment.

Without electricity, there came a major shift in what I perceived to be stimulating. Without the distraction of movies, blogs, and iPods, I found myself spending more and more time observing whatever landscape I was in.

I had the privilege of witnessing the mating ritual of dragonflies, and I watched armies of ants work tirelessly in bringing food to their headquarters. I watched a lightning storm erupt over the sea’s horizon, from the silent viewpoint of a secluded clifftop, and I listened to the haunting howl of gusting winds that slowly gave way to the rhythmic pitter-patter of pelting hail. And although nothing quite compares to the lonely vulnerability of a cliffside storm as experienced from the inside of a van, I have renewed appreciation for the sheer volume of engaging, natural phenomena we are perpetually surrounded by. And we needn’t be knee-deep in alpine snow to appreciate this gift: I have a friend living in central London who introduced me one morning to the twelve species of birds viewable from his window that overlooks a concrete street.

He also introduced me to the idea that all it takes is a willingness to be interested to render our surroundings more interesting.

7/ Waking up in natural surroundings drastically alters the course of one’s day.

I love being able to wake up, open the door, and absorb a view of the mountains or sea from my bed in the morning. When not living in a van, that might not always be a practical option. But I did notice that this unhindered connection with some part of the natural world upon waking instantly brought me into a sort of present-focussed mindset, and a happy one at that.

Now that I’m home, I try to motivate myself (I know it’s hard when it’s cold!) to run outside as soon as I wake up and put my bare feet in the grass for a few moments. If I’m not able to do that, I at least open a window and take a few deep breaths of outside air. Starting the day by connecting with something bigger than me helps towards tapping into a healthy perspective, and serves as a reminder that I am but one small part of a much greater whole.

8/ Easy access to electricity really affects the hours one keeps.

I made the choice to simplify the functioning of my van by avoiding any electrical use when parked. I have a couple of AA battery-powered light sources and a stack of candles, but beyond the gas cooker, it’s just fancy camping. Meaning it’s impossible to ignore when the sun is rising or when it’s setting.

A bit like when you’re camping and you want to have your tent already pitched and your fire lit before it gets dark, van living is at it’s most pleasurable when you have found a suitable spot to park for the night before it’s actually night. Scouting a spot, cooking dinner, or having a bathroom break all become significantly more treacherous in the dark. In the same vein, once dinner has been cleared away and the sheets laid out, there is not much to do besides read and go to sleep. Depending on the time of year and what latitude I was in, this meant sometimes going to bed around 8PM! The thing is, I was never acutely aware of the time because my circadian rhythm naturally wanted to align with the rising and setting sun. Not having to set an alarm clock, yet being able to wake at dawn worked wonders on my energy levels.

To maintain this alliance with the natural flow of the day now that I’m home, I try to sleep with my blinds open in order to let the morning light wake me. In the evening, I try to minimize use of electrical light in any form once the sun has gone down. Sometimes that means lighting a shit ton of candles. And sometimes it’s not really an option, in which case I would opt for at least some dimmer lighting and activating F.lux on my laptop if I need to keep working.

There is something infinitely soothing about a candle being the last form of light I see prior to sleeping, and blowing it out before my head hits the pillow becomes the swift, slumber-inducing signifier that the day has come to a close.

9/ Water, warmth and safety are no longer

evertaken for granted.

I’d like to think that I have always been grateful for these three luxuries. But in retrospect it was an idle gratitude. Since sleeping (or not sleeping) through shivery nights that actually caused my cooking oil to solidify and develop frost patterns, listening fearfully as someone attempted (unsuccessfully) to break in when I was about to fall asleep alone in a remote area, and noticing just how much water I use daily once I could only store a limited supply, not one day goes by without me feeling palpably grateful for the aforementioned comforts. Whenever I enjoy a hot shower, pour drinking water from the tap, or slide into a soft bed with the sense that I am safe, I say thank you. I’m not sure to who or to what, but I feel thankful nonetheless. I only have to flip open a newspaper to be reminded that this triad is not a given, and I never want to take my current fortune for granted.

10/ Fears are often based on what others have said, not what you have actually experienced in your own life.

I know it might sound like an odd lesson to include, especially given the divulgence regarding a fearful incident in the previous point, but I lived through it and am literally here to tell the tale. But immediately after that experience, I noticed a big change in my approach to the journey. A sense of unease had permeated my exploration, and I was always a little nervous. This sensation was magnified at night, and I would often stay awake—deliriously tired—until sunrise, fearful of what might happen, and then admonish myself in the morning for being so stupid when, clearly, everything was fine.

The sub-lesson: Fears can drastically affect your enjoyment of a present experience—one you will never have the opportunity to live again.

“Fear is not real. It is a product of our imagination, causing us to fear things that do not at present, and may not ever, exist. Do not misunderstand me, danger is very real, but fear is a choice.”

— Will Smith in After Earth

That’s right. I just quoted Will Smith. But honestly, who’s gonna argue with it?!

I don’t want to downplay the existence of danger, but from personal experience I can only deduce that fears are much more common than genuine danger.

“If one wastes time and energy worrying about things that may or may not be threatening, one might miss the real threats. I asked myself two questions: statistically, what should I be afraid of? Statistically, what is most likely to kill me or harm me? The answers I came up with were traffic accidents, dehydration, food poisoning, and sunburn. Instead of trying to fight my worries, I decided to just make sure they were sensible ones. I took a swig of water and went to sleep.”

—Jon Brooks, from Alone in Thailand: How I Built a Meaningful Life from Scratch in 8 Days on a New Continent

The truth is, we don’t know if or when shitty, compromising situations may strike. What I do know is that I sabotaged a lot of potentially peaceful experiences because I let my imagination run wild with all the uncomfortable stories I’ve ever read in a newspaper or seen in a movie.

It’s no easy feat, and it’s definitely something I’m still working on, but I believe combatting irrational fears with experiential confidence is a capacity worth cultivating.

11/ Abundance can be created even from limited resources.

This a fairly broad concept, and could easily inhabit an article all on its own, but I felt it worth including within the context of this topic. Throughout my travels, I would sometimes feel like my resources were restricted, and that for some reason meant that I couldn’t enjoy myself the way I really wanted to. But with further reflection, I often found that what I was attempting to pursue was not the only way to achieve the feeling I was ultimately in search of. If I was able to establish what that feeling might be, then I could look within my existing means to see how I could create it.

Maybe this approach stems from studying at an Arts University, where everyone was always broke but still had to manifest viable creations for deadlines. Maybe it stems from hungrily approaching the fridge as a teenager, surveying leftover rice, half a cucumber, and a jar of mustard and thinking “Hm, what can I make out of this?” Whatever the origin, I found that living in a van increased my capacity to create a sense of fullness, even in unlikely territory.

This lesson was evidenced a few weeks ago when what at first appeared to be a bleak and uninspiring place to spend the night swiftly became one of my coziest and philosophically-generative evenings in van-living memory. Even a damp parking lot at a trucker’s fuel stop in suburban France can become the seedbed of warmth and laughter with the right company and some well-chosen groceries. With the curtains drawn, candles lit, music playing, saucepan bubbling, and stimulating conversation in full swing, a deep sense of contentment enfolded me, and I had to remind myself that we were in fact stationed between semis amidst the floodlit expanse of a Shell station.

What we’re presented with may not always adhere to our existing notions of “ideal,” but how we choose to use what we’ve been given can transform the ordinary into the exquisite.

12/ Contentment isn’t derived explicitly from solitude or companionship.

I do believe time alone to be richly nourishing, and van travel certainly gave me a lot of it. By reducing distractions, voices, and influences, we give ourselves the chance to reconnect with our natural state; our natural way of thinking, feeling, and behaving. But the acme of this reconnection is the extent to which it allows us to better connect with others.

There were times on the road when I felt that an experience would have been heightened if shared with good company. And similarly I’ve felt the poignancy of some naturally-ecstatic moments dampened by mis-chosen company.

What I’ve come to conclude is that neither state—solitude nor perpetual companionship—is, in its absolute form, desirable. Rather, it is an abiding balance of both that allows me to appreciate each in equal measure.

I have reveled in the chance to spend one-on-one time with friends who travelled out to meet me at various stages of a road trip. I relish the opportunity provided by arbitrary surroundings that prompt us to be more fully present with each other, and to enjoy the transient nature of life in its most obvious expression. I have similarly reveled in the moments that I was able to spend one-on-one time with myself; uninterrupted and uninhibited. In balancing both states of living, I am able to continue exploring my unique truth without forgetting that my particular truth is woven into a much larger story.

This cognizance of a larger story, in some ways, informs my malaise when viewing certain “snapshots” via rapidly accessible online media. From my own experience, and with reference to Kerouac’s earlier statement, I know there is more to the picture than meets the eye. And so do you. We know when a scene has been constructed with specific representational intent, and this is where our inner discord has an opportunity to take form.

The dissonance arises from positive and negative responses being generated simultaneously towards a single source. On the one hand, an image has the power to inspire; to exhibit—or remind us of—an expansive, beautiful world that is ripe with possibility.

On the other hand, the majority of these images do not use that power to its full potential, instead opting to showcase a somewhat superficial rendition of what is, in truth, a complex experience.

As explored through this article, there is certainly value to the experiences in question, and now I wonder why that value isn’t being explored more often, particularly through popular lifestyle blogs and pictorial accounts. It seems to me that sharing our difficulties, our vulnerabilities, and our confusion serves to foment connections and compassion in a way that is hindered when sharing only our gratifications.

Yet we, as readers and viewers, do sustain the option to apply our own filter to the information provided. What we choose to distill from the content we absorb is up to us. We can choose to ignore our vexation, or we can use it to direct our attention towards our own learning; our own development. We can take time to consider the intricacies inherent in every single snapshot, and how they might relate to our own story.

As with everything that I’ve learned from this experience so far, these lessons seem to be having the highest impact when carried forward out of context. My hope is that my discoveries continue to pervade my non-van life.

After accepting a new job offer, I’ve recently handed my van over to a friend for safekeeping in my absence. I’m headed for a life on water, and I’m pretty sure that cabin sharing is a part of the deal… Luckily, small spaces are my thing.

All in-post images © Nat Dollin 2017

HighExistence created a new tool to help you spend more time living. You’re going to want to see this.

—

Good reads for inspiring simple living:

Timeless Simplicity by John Lane

Timeless Simplicity is a beautifully written, comprehensive exploration into the true cost of our purchases, and the effects they have on our souls’ misguided quests for contentment in the modern world.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd

The Living Mountain is a meditative account of the eastern Scottish Highlands as experienced via the senses rather than by numerical analysis or record-setting. Shepherd’s stance differs from most mountain literature in that it focusses on the sensibilities and subtleties of wandering, as opposed to climactically focussing on the summit.

The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac

The Dharma Bums is a must-read for all wandering, wondering, Zen-inspired seekers. Apart from being riddled with contagious joy and zest for life, the book also offers some humorous yet worthwhile commentary on the differences and similarities between anything and everything.