Jordan Bates • • 23 min read

7 Spiritual Beliefs That are Probably Bullshit

I consider myself a deeply spiritual person.

I’ve had mystical experiences in which the boundaries between myself and all the cosmos seemed to dissolve, revealing the inseparability of all things.

Experiences in which I felt universal empathy and compassion for all creatures wandering through this same labyrinth of creation.

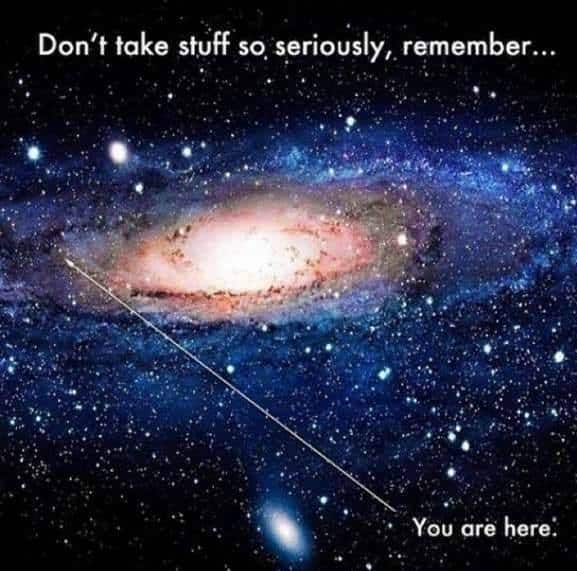

Experiences of soaring, breathless awe and wonder in the face of our sublime and incomprehensibly vast universe.

Such experiences have left me with a deep reverence for the grand riddle of Nature—a reverence that is surely spiritual.

And yet…

I also realize that spirituality has a dark side.

There are many beliefs and ideas in the world of spirituality that can be misleading, self-sabotaging, and even downright destructive for humanity.

Today I want to put a few of these beliefs under the microscope.

7 Spiritual Beliefs That are Quite Possibly Bullshit

My goal is to invite you to question various stagnant, sneaky, misleading, and/or insidious spiritual beliefs that may have taken root in your minds.

The aim here is not to shit on spirituality.

I personally believed some version of most of these ideas at some point in the past, so I know how attractive they can be.

But I didn’t stop questioning, and my views kept changing.

I’ve learned that if you remain open and curious, there always seem to be deeper levels of understanding.

If there’s one thing you take from this article, I hope it’s the inspiration to Never. Stop. Questioning.

Let’s get into it.

1. The ego is an enemy that needs to be eliminated.

Many spiritual people are, ironically, obsessed with the ego—the “I,” the personal, conscious self.

Depending who you ask in spiritual communities, you’re likely to hear that the ego is the evil root of most of our problems. Thus, the ego needs to be destroyed, removed, and/or revealed as an illusion.

This attitude creates a paradoxical internal situation rife with cognitive dissonance: It places you in a position of being at war with yourself.

“There is something evil inside you that needs to be rooted out, done away with,” the ego-haters proclaim.[1]

This attitude is toxic. It creates a sense of guilt and a feeling of being trapped in a hopeless predicament. One imagines that somehow one needs to “ascend” beyond one’s identity and self in order to become a genuinely “good” or “enlightened” person. This sounds suspiciously like a reformulation of Christianity’s “original sin” narrative.

But relinquishing the ego is monumentally difficult, perhaps impossible. Even if our selves do not have any essential nature, as Buddhism teaches, the vast majority of us are never going to transcend our personal identities and narratives, or let go of all of our attachments, desires, preferences, and expectations.

And would we actually want to? Aren’t such things important components of our individuality?

I’m all for gradually letting go of everything that does not feel authentic to oneself. Hell, I’m all for letting go of most things and giving very few fucks, but to me it’s also essential to reserve a few remaining fucks for the things I care deeply about: enjoying life, spending time with loved ones, creating useful and/or beautiful things, improving the world, traveling the Earth, and learning endlessly.

Instead of trying to eradicate our personal identity, we’re probably better off working to accept ourselves just as we are, while also cultivating spaciousness within our minds, so that we may see ourselves more clearly, take ourselves less seriously, and refrain from over-identifying with our personal identity and narrative, instead learning to see it as one of many possible stories about who we are.

Meditation can help us with this. Non-judgmentally observing our minds, without assigning fixed meanings to anything, creates the space we need to see ourselves clearly. It creates the space to stop living reactively, which increases freedom.

This isn’t about eliminating the ego; it’s simply about creating the space to see it clearly. In doing so, one comes to see the ego as more of a wily friend, a tool, an amoral container of individuality, and a bundle of sometimes useful, sometimes counterproductive processes. This distancing process can be seen as a means of overcoming the ego without demonizing or destroying it.

Joseph Campbell was referring to this process of reframing our relationship to the ego when he wrote, “How to get rid of ego as dictator and turn it into messenger and servant and scout, to be in your service, is the trick.” This reframing process is a means of working usefully with the ego, and letting it go to a healthy extent, without feeling the need to demonize or destroy it.

A fundamental precept of Tantric Buddhism is that you are just fine, right now, just as you are. This is a more empowering, productive, and calming starting-point for self- or spiritual development than, “There is an evil selfish part of you that needs to be destroyed.”

Knowing that you are fine just as you are does not preclude the possibility of continuing to learn, grow, and walk an ever healthier and more meaningful path. As David Chapman writes, “Tantra allows you to view your counter-productive habits with some affection and humor—even as you try to overcome them.”

Your ego is not evil. It is not your enemy. Befriend it. Observe its peculiar movements. Train it, through good habits of body and mind, to be a noble actor in the world.

2. Violence is never justified.

There’s a strong tendency toward pacifism in much of the spiritual community. This is definitely understandable. I’m probably some kind of pacifist myself. I deeply hope that peace, cooperation, love, and understanding will win out over the forces of division and violence that threaten to tear our world apart.

However, some people take this position too far, adopting absolute pacifism and asserting that violence is never justified.

This argument breaks down when scrutinized. Let’s say I’m a father, and I’m outside on a walk with my 5-year-old daughter. Suddenly, an obviously deranged person leaps out of a bush wielding a knife. He takes one look at my daughter, raises the knife, and starts charging toward her with a wild look in his eyes. In this situation, an absolute pacifist would hold that I should not defend my daughter. I should simply try to run away or reason with the violent individual. This seems self-evidently absurd.

We can make this even more clear-cut. Let’s say, by some twist of fate, I find myself tied up by a terrorist who is torturing my family and shows every sign of intending to murder them. In my hand, by some great fortune, I have a remote control. If I push the button on the remote, a device previously implanted in the terrorist will activate, and he will be poisoned to death. Absolute pacifists would say that I am not justified in pushing the button. Me? I would mash that button, and I’d seriously question the character of anyone who wouldn’t push it.

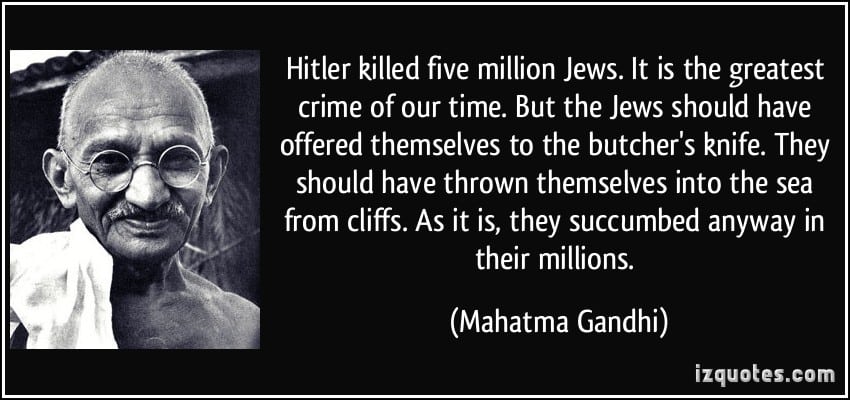

Absolute pacifism looks even more dubious when we consider violence on a mass scale. In World War II, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were hell-bent on world domination and unprecedented genocide. We can assert with near certainty that nothing short of violence could have deterred them from this mission. An absolute pacifist would be forced to conclude that the Allies should have simply surrendered, ran away, hid, or tried to reason with the Axis powers. In an interview after World War II, Mahatma Gandhi, perhaps history’s most famous pacifist, made this shocking statement:

“Hitler killed five million Jews. It is the greatest crime of our time. But the Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs… It would have aroused the world and the people of Germany… As it is they succumbed anyway in their millions.”

Gandhi actually went as far as to suggest that millions of Jews should have simply “offered themselves to the butcher’s knife” in order to “arouse the world.” I have a lot of respect for Gandhi’s accomplishments, but here he went too far. Ironically, even if the Jews voluntarily surrendered their lives and “aroused the world,” what exactly could the world have done about it, if they too took a completely non-violent approach? Absolutely nothing. In some cases, violence is necessary to neutralize an evil enemy attempting to take innocent lives. Even Gandhi acknowledged this truth in ‘The Doctrine of the Sword‘:

“Thus when my eldest son asked me what he should have done, had he been present when I was almost fatally assaulted in 1908, whether he should have run away and seen me killed or whether he should have used his physical force which he could and wanted to use, and defended me, I told him that it was his duty to defend me even by using violence. Hence it was that I took part in the Boer War, the so called Zulu rebellion and the late war. Hence also do I advocate training in arms for those who believe in the method of violence. I would rather have India resort to arms in order to defend her honor than that she should in a cowardly manner become or remain a helpless witness to her own dishonor. But I believe that nonviolence is infinitely superior to violence…”

As a final example, consider the most clear-cut case I can think of: A terrorist has gotten his hands on a molecular nanotechnology weapon. Unless he is stopped, he will unleash a swarm of self-replicating nanobots that will promptly convert the biosphere into a heap of trillions of nanobots, destroying all life on Earth. This is the classic “grey goo” doomsday scenario. You happen to be a sniper who is watching the terrorist from a mile away. You can see clearly that he’s about to use the weapon. There’s no time for any other course of action. You either shoot him and neutralize the threat, or you allow the complete destruction of life on Earth. Anyone who would not pull the trigger in this situation seems to me to be profoundly unethical.

Now, admittedly, this is a question of morality, and as far as I’m aware, there is no objective standard of morality, so there’s no way I can prove that absolute pacifism is an incorrect stance. I hope, however, that these examples have elucidated that absolute pacifism, when taken to its logical conclusion, allows for monumentally fucked up things to happen that could have been prevented. Again, I’m nearly a pacifist. I think violence should be used only in rare and extreme circumstances. But in some cases, it’s overwhelmingly clear to me that violence is not only justified, but an ethical imperative.

3. Culture and/or society are nothing but oppressive forces.

This is something of a classic hippie idea, similar to Terence McKenna’s famous meme, “Culture is not your friend.“

Like many countercultural viewpoints, there is some truth in the idea that culture and society are cold soul-crushing machines, but it can be taken too far, to the point of becoming an extreme and reactionary viewpoint.

Cultures and societies are inevitably somewhat oppressive for everyone who exists within them. This is because (if for no other reason) they come with a whole bunch of norms—standards of acceptable and unacceptable behaviors—and they pressure the people existing within them to abide by these norms. And invariably none of us fit perfectly into these societal molds; we have plenty of whims, desires, ideas, fantasies, and dreams that are considered out of bounds. This conflict sucks. It creates a lot of suffering.

But this is only one side of the coin.

Jordan Peterson has noted that society is simultaneously a tyrant and a wise king. The tyrant is the oppressive side that forces you to conform in ways that conflict with your true desires. The wise king, however, is the side that many anti-establishment types overlook.

Humans are known to have a negativity bias: negative events impact us more deeply, and we tend to focus on the negative aspects of things, often blinding ourselves to the positive. Nowhere does this seem more true than in discussions of culture and society among countercultural folks. “The Man” is nothing but a nasty dictator who just wants to “bring us down” and ruin all our fun, or else society is actually just a giant Huxleyan conspiracy to dumb down and enslave everyone.

But what about all of the miraculously good, life-improving aspects of our modern cultures and societies?

Consider the supercomputer you’re using to read this—the same one that gives you instantaneous access to humanity’s accumulated wisdom, most of history’s manmade beauty, and any other human with a computer, anywhere on the planet.

More fundamentally, consider the elaborate supply chains and systems of agriculture we’ve devised that manage to feed nearly all of the 7.6 billion of us, while requiring only a tiny percentage of us to actually work on food production and distribution. In the absence of these systems, most all of us would need to be small-scale farmers and/or hunter-gatherers, and there’s no way we’d be meeting and exceeding most of humanity’s basic needs as well as we are currently.

Think about plumbing systems, transportation networks, systems of cooling and heating, reliable structures to live/work in, running water, toilet paper, medical technology, comfortable clothes and furniture, refrigerators, ovens, electricity. These things were painstakingly invented over the course of centuries because we created this walled garden called civilization that shielded us from the vicious death-maze of the natural world and freed up a lot of our time to work on making cool shit to improve our lives.

Nowadays billions of us live in a veritable techno-wonderland in which life is more comfortable than ever before; in which each of us has incalculable technological power at our fingertips; and in which we’re largely free to live our lives however the hell we want. Not to mention that we’re all less likely now than ever before to live in extreme poverty or die at the hands of another human being.

And let’s not forget about the non-material inventions most of us reading this enjoy and benefit from: freedom of speech, basic human rights, freedom of artistic expression, equality of opportunity, civil liberties, the right to a fair trial, etc.

Our ancestors figured out a veritable Everest of useful and amazing shit, and it’s all built so seamlessly into our lives that we barely notice it. We shouldn’t underestimate how difficult life was in the state of nature, or how much blood, sweat, and tears have been shed in order to create the advances that have turned our world into a kind of Shangri-La our distant ancestors wouldn’t even recognize.

It’s a miracle that things function as well as they do, and this miracle was made possible by many millennia of individuals laboring to create more wonderful cultures and societies. Our cultures and societies represent an age-old legacy, a birthright passed down through countless generations. Let’s not be so quick to want to scrap them. Let’s not commit the Nirvana fallacy and judge our actual world by comparing it to an idealized fantasy of a non-existent utopia.

And yes, what we’ve got is still far from perfect. And yes, we should keep imagining ways to make it all much better. And yes, it sucks to feel the pressures of society. But if we have integrity, we won’t focus exclusively on these truths without also acknowledging everything awesome and high-functioning about our present situation.

4. Meditation is a purely positive experience.

A lot of people in the spiritual community are meditators and meditation advocates, which is great. Meditation is a tool for self-awareness and self-liberation that has been used for thousands of years. Numerous scientific studies have suggested a number of marvelous benefits that come with meditation practice. And meditation challenges form the core foundation of our course, 30 Challenges to Enlightenment. We love meditation.

With that being said, many people have a misconception of what meditation is or can be. Within the spiritual community, a common image of a meditator is that of a person sitting cross-legged in silence with a slight smile on their face, perhaps in a natural setting. Meditation is associated with inner peace, realms of light, a transcendence of darkness and worldly concerns. It’s often viewed as a purely positive experience, akin to floating away on a soft cloud of bliss.

But meditation is not all fun and games. Sure, when you first start meditating, you’re likely to have a pretty chill, peaceful experience. You’re just sitting quietly, focusing on your breathing, and returning your attention to your breath when you get distracted. All is well. This might be your experience for years.

But if you progress far enough with meditation, you’ll almost certainly encounter things that aren’t so rosy. In essence, advanced forms of meditation are means of directly observing your own mind, drilling down into your psyche to see yourself and your existence as clearly as possible and to accept reality non-judgmentally.

Eventually this process will lead you into “the places that scare you,” as Buddhist teacher Pema Chodron puts it. Meditate for long enough and you will be confronted with your deepest fears. You will come face to face with the fact of the inevitable deaths of you and everyone you love. You will uncover your own shadow—the parts of yourself that you reject, repress, and normally refuse to look at; the memories, impulses, urges, and desires that your society deems taboo. You will see yourself clearly, in all your beauty and hideousness, and you will need to find a way to accept who you are.

This is not to be taken lightly. Eventually, meditation will likely transport you into your own personal hell, and you’ll have no choice but to find your way through it. Granted, on the other side of this hell you may realize mythical levels of spacious awareness, acceptance, and freedom. But getting there is no joke.

If you take meditation seriously enough, you’ll likely eventually reach a point where you need a supportive meditation community, or an experienced teacher or guru, to guide you forward in the process. Vinay Gupta, a meditation expert, has even suggested that it’s a good idea to spend substantial time with a psychologist prior to diving too deeply into meditation, in order to start navigating your shadow and unresolved traumas with an expert, prior to encountering these things solo through meditation. This is an especially good idea if you’re depressed or otherwise mentally unwell.

This side of meditation is rarely discussed. If one looks only at the popular culture surrounding meditation, one would never guess that the practice can (and eventually probably should) take you to the darkest internal spaces you’ve ever visited. But this is the truth, and more people need to be aware of it.

If you’d like to build good long-term habits and deepen your spirituality, consider taking 30 Challenges to Enlightenment.

5. The differences between religions are unimportant because, at root, they’re really all saying the same thing.

Maybe you’ve heard of the “perennial philosophy,” which refers to the idea that all religions, beneath their surface differences, actually point to the same fundamental Truth.

This idea is fundamental to the New Age movement and has been championed by luminaries such as Aldous Huxley and Joseph Campbell.

In his 1945 book, The Perennial Philosophy, Aldous Huxley defined the perennial philosophy as:

“… the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical to, divine Reality; the ethic that places man’s final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being; the thing is immemorial and universal. Rudiments of the perennial philosophy may be found among the traditional lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions.”

Joseph Campbell, in a similar vein, suggested that all religious mythologies contained metaphors pointing to the same great and awe-inspiring mystery of being confronted by all humans across time and space.

Now, let me say first of all that I have tremendous respect for both Campbell and Huxley, and I think these brilliant thinkers were onto something regarding this universal element found in all religions.

I think there is a strong case to be made for the idea that mystics throughout history, in different traditions, had similar earth-shattering experiences of the Cosmos, the Mystery, divine Reality—whatever you wish to call it—and simply interpreted and expressed their experiences through whatever their particular cultural and mythological lens happened to be—and that these culturally specific stories about mystical experiences became foundational aspects of many religions. I’m not sure if all mystics were really talking about the same thing or if all religious mythologies indeed point to the same thing, but it’s a fascinating possibility to consider.

Even though I believe there is merit in what Huxley and Campbell were saying about the perennial philosophy, I think their espousal of this viewpoint had unintended and pernicious consequences.

The perennial philosophy has become quite popular in spiritual circles, resulting in many people believing some version of the following:

“The differences between religions are trivial and don’t really matter, because when you get down to it they’re really all about peace and love and the one Divine Reality.”

This is a hazardous over-simplification.

For one, this viewpoint is a readymade reason to dismiss and shrug off the mountains of specific practices, intricacies of belief, artifacts and objects, ideological nuances, geographical and historical contexts, esoteric rituals, distinct sects and denominations, and numerous other aspects that clearly distinguish religions from one another. Religions are among the richest and most complex human social phenomena, and to wipe away their countless differences in service of a reductive “all religions are the same” narrative is to ignore a chance to marvel at the diversity of humanity.

Beyond that, it’s just not true that these differences are trivial. Is it really trivial that most Buddhists don’t believe in any god or deity, while Catholic fundamentalists believe in a wrathful male god who watches all of our actions and will send us to an eternal pit of torture and flame if we misbehave too often? Or that various modern incarnations of Islam(ism) limit women’s rights in significant ways, while most other modern religions do not do so (to the same extent)? Or that Pagans believe in worshiping and preserving the Earth, while the Christian Bible tells us we are meant to “rule over” the animals and all the Earth? Should we ignore the complex and extensive history of religiously motivated violence, or the fact that some modern religions seem to inspire more violence than others?

Ignoring the differences between religions is not only too simplistic, it’s irresponsible.

While it’s that most religions have some significant and heartening general similarities, the details matter as well. Religions are massive ideological and cultural structures undergirding a colossal amount of human activity in the world today, and we need to be able to distinguish between them in order to criticize their unique flaws and applaud their unique boons.

In addition to uncovering hidden metaphors indicating universal religious messages, it’s important also to look at what modern adherents of various religions actually believe and do. We need to balance celebration of commonality with acknowledgement of distinctness, complexity, and nuance.

Because at the end of the day, religions aren’t just their ideals and messages in a vacuum; they’re also the combined activity of everyone who believes in them. They’re ideological software programs carried around and acted out by real-world, flawed human beings. I’m all for comparative mythology and its profound unifying lessons, but in order to understand religions and guide them in a wise direction, we need to observe how they function in the real world, and we need to be honest about their similarities and differences.

6. All is One. “You” are an illusion.

Many spiritual people proclaim versions of the idea that “All is One,” that “you are the universe,” that boundaries do not actually exist.

We should distinguish this view from the view that human beings are continuous with the universe—that we do have individual existences, but that we are also inseparable parts of the whole interdependent process of reality. This view was expounded especially eloquently by the late Alan Watts:

“You are an aperture through which the universe is looking at and exploring itself.”And on another occasion:

“You are a function of what the whole universe is doing in the same way that a wave is a function of what the whole ocean is doing.”

Such statements place Watts in a camp similar to that of Carl Sagan, who posited that we are “a way for the cosmos to know itself.” But others take a more extreme view, holding that you simply are the entire universe, and your individual existence is something to be regarded as a persistent delusion. In philosophical terms, this position is known as monism, which can be contrasted with dualism—the view that reality contains unambiguously separate objects.

Prior to the countercultural era of the 1960s, the Western world had for many centuries been fairly heavily entrenched in the dualist point of view. Alan Watts and others rebelled against this status quo, calling attention to the interconnectedness of all things and the ambiguous nature of the boundary between the self and reality.

The mistake of some of these teachers was that in rebelling against dualism, they swung the pendulum too far in the opposite direction, embracing pure monism. If you’ve ever had the intuition that there is more to the story than “All is One,” you’ve detected the trouble with monism: It doesn’t recognize the specifics of the world, the uniqueness of individuals, and the most basic thing “common sense” tells us about ourselves: that we are, at least in some sense, distinct from everything else. In a poignant critique of monism, cognitive scientist David Chapman writes:

“If All is One, then there is no boundary, and you are really the entire universe. Typically, monists say that the universe is equivalent to God, so you are actually also God. As you realize everything is totally connected, you develop the ability to affect anything you want.

This is the ultimate fantasy of power and invulnerability. However, convincing yourself that you are All-powerful, when you aren’t, does not make your life go well.

When the fantasy collides with reality, monists retreat into a make-believe magical world. Monism produces dreamy spaciness, refusal to make any clear distinctions, refusal to judge. This leads to drifting through life, expecting other people to clean up your messes, contributing nothing except spiritual clichés mouthed at unwanted times.”

Chapman points out that monism tends to lead to bad outcomes. It’s pretty difficult to establish and maintain strong boundaries if you truly believe boundaries don’t exist and your individual self is an illusion. But in the trenches of day-to-day life, maintaining healthy boundaries, distinguishing between people, and taking responsibility for yourself are of course indispensable skills.

Chapman goes on to suggest that both monism and dualism are incorrect and proposes a “complete stance” called “participation” that combines the correct aspects of both monism and dualism. He defines “participation” as follows:

“Participation is the stance that revels in the extraordinary variability of the world, that loves and engages with specifics and individuals; and also appreciates the porous self/other boundary, works skillfully with diverse connections, and accepts responsibility for whatever you encounter.”

In other words: You are an inextricable portion of the reality-process that may or may not have begun with the Big Bang. You are comprised of the same atoms as everything else. In some sense, you are the universe. But in another sense, you’re definitely you, distinct from everything else. “Participation” is an approach to life that acknowledges and integrates both of these truths.

To the extent that some spiritual people insist that we are all simply the universe and nothing else, I respectfully disagree. In embracing “All is One,” they overlook the valuable aspects of dualism: that (porous, ambiguous) boundaries do exist, and that this allows for individuality and for the game of human existence to occur.

7. You have to believe in something to be spiritual.

This myth is probably circulated more outside the spiritual community than within it, but it’s really worth mentioning here.

There’s a toxic stereotype of spiritual people as necessarily believing in a bunch of questionable pseudoscientific stuff, like the Law of Attraction, the coming of the Age of Aquarius, the third eye, the healing power of crystals, or whatever this meme is making fun of:

Harmless lolz aside, I’m not here to bash on people who believe in such things or to assert that such notions are definitely false. I’m ultimately agnostic about almost everything. Whereas most people think in terms of either believing in something or not believing in it, I think of my viewpoints in terms of how confident I am that something is true, and I’m never 100% sure. This approach is similar to Bayesian thinking.

The point is that I try not to believe in anything absolutely.

You might wonder, “Wait, is it really possible to be deeply spiritual without any kind of real faith or belief?”

It is, indeed! :)

Take a look at people like Robert Anton Wilson, Carl Sagan, Sam Harris, Albert Einstein, and Terence McKenna—all deeply skeptical, scientifically minded, and deeply spiritual in some sense. I suspect there are millions of people like this.

I’ve quoted Carl Sagan on this point many times previously, but hell, once more can’t hurt:

“Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual. So are our emotions in the presence of great art or music or literature, or of acts of exemplary selfless courage such as those of Mohandas Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr. The notion that science and spirituality are somehow mutually exclusive does a disservice to both.”

Or consider the words of Einstein:

“The finest emotion of which we are capable is the mystic emotion. Herein lies the germ of all art and all true science. Anyone to whom this feeling is alien, who is no longer capable of wonderment and lives in a state of fear is a dead man. To know that what is impenetrable for us really exists and manifests itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty, whose gross forms alone are intelligible to our poor faculties — this knowledge, this feeling … that is the core of the true religious sentiment. In this sense, and in this sense alone, I rank myself among profoundly religious men.”

Spirituality, in my view, is above all a capacity for what Einstein calls the “mystic emotion,” elsewhere translated as an experience of “the mysterious.” When we gaze upwards at the stars and sense the sheer magnitude of this cosmos in which we find ourselves—when we, through science and dedicated inquiry, begin to glimpse the glorious intricacies of the natural laws and subatomic building blocks that make up the visible world—we feel a sense of awe at the ineffability, inscrutability, and magnificence of this universe in which we find ourselves. We marvel at the sliver of this grand design which we are able to fathom with our feeble ape minds.

Absolute belief is not necessary for this form of spirituality. If anything, the assumption of final knowledge may detract from one’s ability to truly taste the oceanic mystery of this miraculous existence.

Conclusion: Beware of red pills.

Most of the ideas I refuted in this article have something in common: They’re red pills.

By “red pill” I mean an idea that makes you feel like you’re in on a giant earth-shattering secret—an idea that makes you feel you’ve “woken up” from the matrix that most people are trapped in because you now know The Real Truth.

Red pills are everywhere, not just in the spirituality memespace. Various movements and communities all over the world are peddling different forms of The Knowledge That Will Change Everything For You.

I’ve taken a lot of red pills in my life, and I know how seductive they can be. It feels great to think you’re in on some precious secret and more enlightened than all the “sheeple” who can’t see the truth.

The problem is that the vast majority of red pills turn out to be bullshit in some way. Usually they’re too all-encompassing, a new form of dogma: “Reality is the EXACT OPPOSITE of everything you’ve been taught!!”

No, usually it isn’t. It’s somewhere in-between. Reality can rarely, if ever, be characterized by sweeping, all-encompassing generalizations. Things are too complex. But because our minds crave security and certainty, it’s easy to swing from one form of Gospel to another.

Instead of doing this, I humbly submit that it’s better to learn to allow room for complexity and ambiguity. To be highly skeptical of any claims to Final Answers and instead assume that our current answers and models are incomplete, in need of further refinement.

If we’re able to do this, the world opens up to us. When we relinquish the need for certainty, curiosity is allowed to blossom, and the world becomes a never-ending series of interesting questions and investigations, with endless exciting new perspectives to gain.

When we embrace ambiguity, we stop living reactively based on our idea of fixed truth; we stop insisting on the correctness of our views and feeling insecure when others disagree. This is liberating—a weight off our shoulders, a new sense of spaciousness in which we can simply listen to what others are saying and see many perspectives on any given issue, situation, or conflict.

In sum:

I don’t have all the answers.

Spiritual people don’t have all the answers.

No group in human history has had all the answers.

If you ever feel like you’ve got everything figured out, it’s probably time to take a step back.

As Robert Anton Wilson put it, “Only the madman is absolutely sure.”

Cheers to curiosity, questions, and endless learning.

Peace and love, humans.

If you’d like to deepen your spirituality, consider taking 30 Challenges to Enlightenment.

Footnotes:

[1] I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this attitude seems a lot like a repackaging of Christianity’s “original sin” hypothesis. Many New Age and spiritual ideas seem to be rebrandings of much older religious ideas, Christian or otherwise (e.g. Note the sameness of, “Thank you, Universe. I know you will protect me.” and “Thank you, God. I know you will protect me.”).

Edit: A previous version of this article reported that Gandhi did not believe violence was justified under any circumstances. Additional information I discovered revealed that he did in fact acknowledge that violence was justified on rare occasions. The article has been updated to reflect this discovery.

Jordan Bates

Jordan Bates is a lover of God, father, leadership coach, heart healer, writer, artist, and long-time co-creator of HighExistence. — www.jordanbates.life