Steve Taylor • • 5 min read

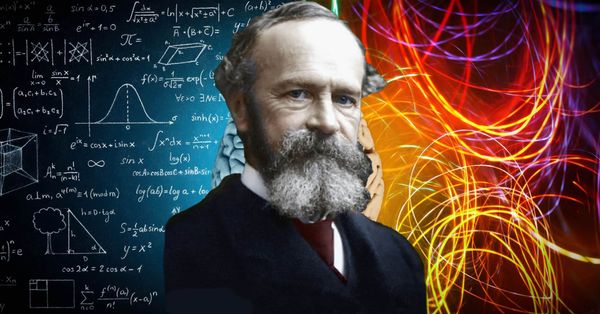

The Genius of William James: The Clairvoyant American Psychologist

In all my years of writing and lecturing about psychology, there is a phenomenon I’ve grown accustomed to: Whenever I come up with a “new” idea or theory, I eventually find that there is one psychologist who has addressed the topic before me: William James.

Although he is well recognised as one of the founding fathers of psychology, the range and the timeless relevance of William James’ writings and theories never cease to amaze me.

One of the first books I wrote was about the perception of time.

In Making Time, I put forward an “information processing” theory of time, suggesting that the more information our minds process (that is, the more perceptions, sensations, thoughts and so on) the slower time seems to pass. I argued that time seems to go slowly for children because the world is so new to them, and so they are processing much more perceptual information. I suggested that one of the reasons why time seems to speed up as we get older is because the world becomes gradually more familiar to us, and so we process fewer new impressions. I thought I had come up with something new but soon found that William James had put forward a similar theory.

In The Principles of Psychology, he described how children’s slowed sense of time was due to the fact that, “in youth, we have an absolutely new experience, subjective or objective, every hour of the day… but as each passing year converts some of this experience into automatic routine which we hardly note at all, the days smooth themselves out in recollection to contentless units, and the years grow hollow and collapse.”

Another area that has always interested me is the psychology of warfare.

My interest in this topic stemmed from my reading of anthropological and archaeological texts that suggested that warfare only became endemic in fairly recent times (that is, about 6,000 years ago) and that in prehistoric times, group conflict was surprisingly uncommon. This led me to believe that warfare was primarily a psychological phenomenon, rather than one rooted in human biology or evolution. And again, I quickly found that William James had already reached a similar conclusion. In his seminal essay “The Moral Equivalent of War” (1910), James suggested that warfare was so prevalent because of its positive psychological effects, both on the individual and on society as a whole.

On a social level, war brings a sense of unity in the face of a collective threat. It binds people together, encouraging them to behave unselfishly for the common good. While on an individual level, warfare makes people feel alive, more alert and awake, giving them meaning and purpose beyond the monotony of everyday life. As James puts it, “Life seems cast upon a higher plane of power.” By the term “moral equivalent of war,” James meant that human societies need to find an equivalent activity that brings the same collective and individual benefits of war — without causing death and devastation.

The Transmission Hypothesis

William James was not merely a psychologist, but a philosopher too. And the familiar sensation that “William James got there before me” happened most recently when I also began to write about philosophical issues.

In Spiritual Science, I suggested that the best way to understand human consciousness is to think in terms of an all-pervading general consciousness which is a fundamental quality of the universe (in a similar way to other universal fundamentals like gravity or mass). I suggested that fundamental consciousness becomes manifest in individual life forms as our own personal consciousness, via the human brain. The brain performs the role of receiving and transmitting fundamental consciousness into our individual being.

It wasn’t long before I found out that William James put forward a very similar theory. In an essay called “On Human Immortality,” written in 1898, he suggested that mind, cognition, or mental awareness are the result of the essential reality of the universe being transmitted through the “receiving station” of the brain. James does not attempt to describe the nature of this essential reality, except through metaphors such as air passing through the pipes of an organ, or as invisible light or “white radiance.” But he makes it clear that human consciousness is an influx of this essential stuff. He says that our own “sphere of being” that is of the same nature as “that more real world.”

William James and Post-Materialist Science

In recent times, many psychologists have adopted a materialist perspective which sees the human mind (including consciousness) as a shadow of the brain, an epiphenomenon resulting from the interactions of material particles. This materialistic perspective is skeptical of unusual states of consciousness such as mystical experiences, which are often seen as delusory states produced by aberrational brain activity. There is also skepticism towards ‘psi’ phenomena such as telepathy and pre-cognition, which are seen as impossible because they allegedly break the laws of science.

And part of the reason William James is so important is that, even before materialism became dominant as an intellectual paradigm, he was able to see its limitations. He was open to the existence of psi phenomena, and the possibility of some form of life after death. As his great work The Varieties of Religious Experience shows, he saw mystical experiences—in which a person’s awareness expands and intensifies—as a “window through which the mind looks out upon a more extensive and inclusive world.” He sensed that normal human awareness is restricted and that our normal view of reality is, therefore, unreliable, in the same way that the photos taken by a faulty camera are defective. As James stated, we should not “close our account” with reality (which is what materialists try to do) until we have investigated these different states of consciousness, and acknowledged the insights into the nature of reality that they provide.

This is perhaps why James seems such a contemporary figure. One of the most exciting developments of the last few years has been the post-materialist science movement, founded by a group of scientists (including Mario Beauregard, Lisa Miller, and Gary Schwartz), who believe that the assumptions of conventional materialist science are no longer viable. The post-materialists put forward an alternative perspective, suggesting that mind or consciousness is not derived from matter, but a fundamental aspect of the universe, and that “there is a deep interconnectedness between mind and the physical world.”

In this sense, William James could easily be seen as the patron saint of post-materialist science.

James’ work was so wide-ranging that I have only touched on a tiny fragment of his theories here.

I’m sure there are many other psychologists and philosophers who have found that their ideas and theories were anticipated by him. At some point, all of us who follow in his footsteps are bound to find ourselves exploring areas that he demarcated over a century ago.

It is this uncanny prescience, together with his open-mindedness to non-materialist perspectives, that represents the true genius of William James.

Spiritual Science by Steve Taylor

Are you ready to embrace the possibility of psychic phenomena? Take a scientifically-driven ride deep down the rabbit hole with Spiritual Science, the latest book from Steve Taylor.