Jon Brooks • • 17 min read

How to Overcome Perfectionism: Life Lessons from Kubrick to Picasso

We all know the feeling…

We start a diet and we stick to it PERFECTLY.

Then suddenly temptation gets the better of us…

…we eat ONE bad thing and BOOM.

We binge like there’s no tomorrow, feel guilty, then binge some more.

This is All Or Nothing Thinking – a classic symptom of perfectionism.

But perfectionism doesn’t just affect our diets, it affects our confidence, our relationships, our work, our lives…

…And it needs to be stamped out.

Why Learning From Failure Is ESSENTIAL

In How To Overcome Procrastination And Turn Pro, I briefly explained that we often know what we should do in order to succeed, but find the idea of following our own advice too frightening to act upon.

If we fail under someone else’s council, then surely it is not our competence that is questionable, but the council we have received.

We seek out external resources (like this article) to lift some of the burden of responsibility from ourselves and provide a way of rationalising any potential failure.

The fear of creating art, and the fear of following our own advice, I believe, are symptoms of our proclivity to take failure personally.

We live in a society where everyone is basically given the same opportunities to succeed, and so our eventual position in life, including the successes and failures along the way, are thought of as deserved.

Good fortune is no longer a recognised compliment. Bad luck is no longer a recognised excuse — a man today must make his own.

Society’s seeming equality, coupled the media’s humiliating depictions of failure and the unrealistic models of perfection they present as successes, cause us to avoid failure so much, that we often also avoid taking the risks that are necessary to succeed.

If you read the biography of any successful person you will soon discover that failure and risk are an intrinsic part of success. Moreover, it has been well documented by psychologists that there is a large correlation between how often a person fails and how likely they are to succeed.

The most successful sportspeople, scientists and artists have all failed more than their less successful contemporaries.

The lesson?

Failure is an inescapable part of life and a critically important part of any successful life. We learn to walk by falling, to talk by babbling, to shoot a basket by missing, and to color the inside of a square by scribbling outside the box. Those who intensely fear failing end up falling short of their potential. We either learn to fail or we fail to learn.

– Tal Ben Shahar, The Pursuit of Perfect

Even Plato Had Self Doubt

We tend to think of highly successful celebrities as almost mythical super-humans composed of a separate genetic material than ourselves.

You could argue that the media heightens their extraordinariness to make them more captivating and glamourous. I believe that’s an element of it, but not the whole picture. I think we actually want celebrities to have an other worldly quality to them, not just to make them more captivating, but so that we don’t suffer the envy that would otherwise occur if we thought their accomplishments were within reach.

It is no coincidence that we envy our slightly higher paid co-workers while we happily sit and admire the billionaire entrepreneurs streamed into our homes every night.

We only envy what we believe we are capable of achieving… but haven’t.

Bearing that in mind, it would be unwise of me to tell you ‘you have the power to achieve anything’. But it is worth recognising that the main difference between you and those perfect people you aspire to be like is, ironically, their ability to embrace imperfection, endure suffering, persist against setbacks, stay poised in uncertainty, and override all self-doubt.

The Greeks called it hubris. It has been called sinful pride, which is of course a permanent human problem. The person who says to himself ‘yes I will be a great philosopher and I will rewrite Plato and do it better’ must sooner or later be struck down by his grandiosity, his arrogance and especially in his weaker moments will say to himself ‘who? me?’ and think of it as a crazy fantasy or even fear it as a delusion. He compares his knowledge of his inner private self with all its weakness, vacillation and shortcomings with the bright shining perfect and faultless image he has of Plato. Then of course he’ll feel presumptuous and grandiose. (What he doesn’t realise is that Plato, introspecting, must have felt just the same way about himself but went ahead anyway, overriding his doubts about himself.)

– Abraham Maslow

Read: A Philosopher’s Guide To Facebook Envy

If you’re hoping to succeed without encountering failure, by implication, the only standard you are willing to accept from yourself is perfection. And if you haven’t realised yet, perfection is… not so perfect.

All Or Nothing Thinking

“The maxim “Nothing but perfection” may be spelled “Paralysis”

– Winston Churchill

Perfectionists often wear their perfectionism like a badge of honour. ‘I’m a perfectionist and I accept nothing but the best. If I feel anxious and unhappy, so be it. It is the only road to success. No pain no gain.’

While we now know this not to be true, the perniciousness of perfectionism goes far beyond procrastination, time wasting and the failure to learn from failure.

Perfectionism, left unchecked, can spread throughout our lives like a virus, causing us to project imperfections upon things that, by natures standard, are just the way they should be.

Here’s three examples of how perfectionism distorts our reality, beyond the realms of work:

1) Perfectionists are prone to disorders.

Perfectionists think in an ‘all or nothing attitude’.

If they are not supermodels, they are ugly; if they are not slim, they are fat; if they are not the smartest, they are the stupidest; if they are not first, they are last; if they mess up one part, the whole is messed up; if they want to get fit, they run a marathon.

This is obviously a terribly unhealthy attitude. Thinking in this binary manner will inevitably lead to self-sabotage or, worst yet, a psychological disorder.

Psychologists have studied perfectionists and concluded that they are at more risk of developing eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia than the rest of us. If they eat one wrong food, they feel as though their whole diet is ruined, binge like no tomorrow, feel guilty for binging and binge some more to purge the guilt.

(As a side note, many bodybuilders develop eating disorders leading up to competitions that stay with them long after)

2) Perfectionists have worse relationships.

If our world view proselytises anything less than perfect as abominable, we will assume others also share this belief and as a result, become hypersensitive to any minor fault another may perceive in us.

Along with this hypersensitivity will come defensiveness: the antithesis of intimacy. For there can be no intimacy when there is defensiveness, because true emotional intimacy stems from the trust we place in others by making ourselves vulnerable, and imperfect in their company.

3) Perfectionists have low self-esteem.

Nathaniel Branden, the world’s leading authority on self-esteem, explains in his book The Six Pillars Of Self Esteem, that an essential component of high self-esteem is the ability to be self-accepting.

But how can a perfectionist ever be self-accepting if, to use the old cliche, ‘nobody is perfect?’

The problems with perfectionism are clear and disconcerting. But without a viable solution we are no better off than they are.

Luckily, there is one…

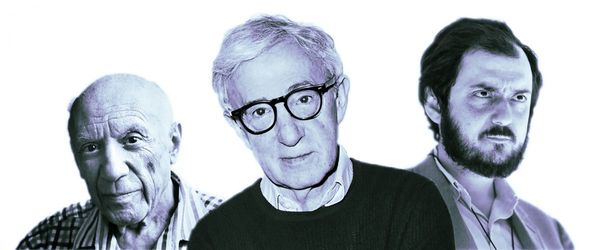

Stanley Kubrick: The World’s Biggest Perfectionist

Stanley Kubrick, one of history’s greatest film directors, after finishing Full Metal Jacket in 1987, immediately began searching for his next novel to adapt. In typical Kubrick fashion he began by voraciously reading everything in sight and even employed teams of researchers to summarise the books he didn’t have time to read himself.

During this intense search, which he did prior to every film, the only sound his assistant, Leon Vitali, would hear coming from his office for months on end, was ‘the thud of books hitting the floor.’

In 1990, literally hundreds of thuds later, his three year search came to an end when he found the book Wartime Lies. It’s subject matter was dark and serious. It was based on the atrocities of World War II and, in particular, the holocaust.

Now the next stage of Kubrick’s research began: to learn everything humanly possible about World War II and the holocaust.

Kubrick’s method for researching a film was simple. When discussing the research he did for his film Dr Stangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, a satirical comedy about the cold war, he described his process as follows:

I stop reading when I can read new books on the subject and fail to learn anything new.

If you are already familiar with Kubrick, examples of his obsessive attention to detail should not surprise you. If you aren’t, here are five more:

- He was famous for shooting excessive amount of takes. When filming The Shining he broke the world record by shooting the same scene 148 times.

- He would often measure his film’s ads in newspapers and call them up if they did not have the exact dimensions (to the mm) he had paid for.

- He wore the same boots as the astronauts on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey so that the footprints on the moon would all be identical to one another.

- Concerned that his cats were over drinking, he called up his vet to find out how many millilitres there were in the average cat slurp. His vet didn’t know. Kubrick later phoned him back with the answer.

- Not being satisfied with the tightness of the lids on the boxes he used for storage, he designed his own and called up the local box manufacturers with the dimensions. His custom box is still in production.

Yes, Kubrick was a massive perfectionist. And similar to the previous examples with the problems of perfectionism, Kubrick’s immersion into the depressing world of World War II, for Wartime Lies, had costs far and beyond the realm of work.

His wife Christiana, in Jon Ronson’s documentary Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes, recalled that:

This was a very dark time period for Stanley… he became depressed’ and would often ‘sit in the corner and sob.

While Kubrick read and sobbed, unbeknownst to him, another filmmaker was working on a project with similar themes to Wartime Lies.

During the last two years of Kubrick’s pre-production, ending in 1993, Steven Spielberg, researched, directed, edited, and released a film called Schindler’s List. It went on to win seven academy awards including the coveted Best Film and Best Director.

Kubrick, still having shot a single scene, immediately shut down production on Wartime Lies. He didn’t release another film for a further six years, making it twelve years from his last.

The Lesson?

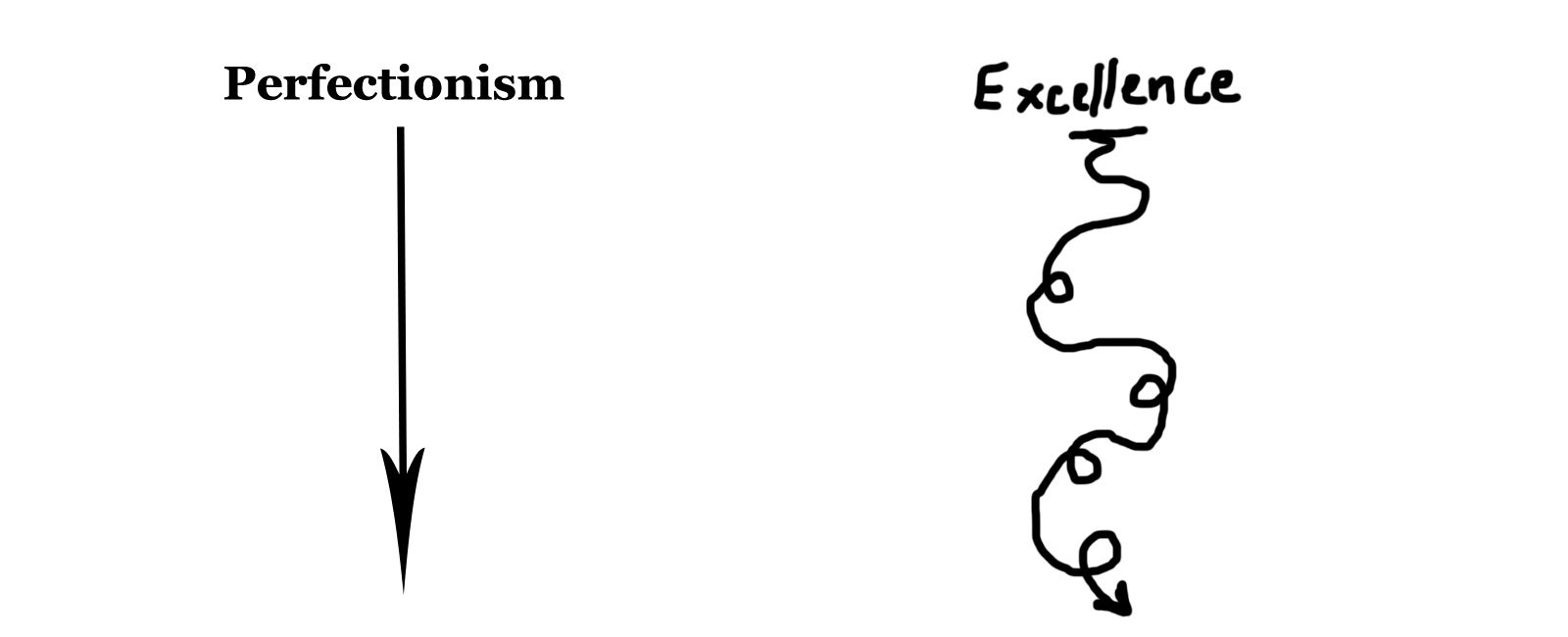

Do not strive for perfection; strive for excellence.

Stanley Kubrick was obsessive in his pursuit of perfection. And while his films are undeniably masterful*, he suffered the common perfectionist ailments: unhappiness and time wasting.

Steven Spielberg, meanwhile, strove not for perfection but for excellence. He was happy to delegate roles, focus on the big picture, work within deadlines, leave the box making to the box makers, cat slurping to the cats and world records to the perfectionists.

(Kubrick became great friends with Spielberg and chose him to direct his script AI: Artificial Intelligence.)

The Messy Path To Success

Those who strive for excellence see failure as an opportunity to learn; understand the path to success is meandering; allocate time reasonably depending on the task; focus on the 20% that provide 80% of the results; view progress as slow and gradual; understand that nothing worth doing is easy; view themselves as a constant working progress; enjoy the process as much as the outcome, and never neglect their wellbeing.

The path to success is not straight, but meandering and messy.

Overcoming perfectionism is not straightforward and easy. Perfectionists will try to interpret the difference between perfectionism and excellence as binary. It is not; it is a continuum.

No one is perfectly perfect or perfectly excellent.

Perfectionists, in trying to overcome their perfectionism, will also often try to do so with the same rigid perfectionism that landed them in trouble to begin with. You must resist this paradoxical temptation and allow yourself to be human, even if it means, at certain moments, embracing your perfectionism.

I’ll now present to you, five further philosophies and case studies on success that you can refer back to while you work. They will also help reinforce the benefits of striving for excellence.

A For Effort

From a young age society conditions us to celebrate the destination instead of the journey. In school we get an A for the exam result, not for the way we study for the exam. If you look at the typical school report you’ll often notice that the children with bad reports are condemned for ‘not trying hard enough, not putting in the effort, talking to much or failing to listen.’

When you look at a glowing report you’ll see children being praised for their ‘intelligence, talent, giftedness, and flair.’ Traits that are fixed and unlearnable. It is no wonder those ‘unintelligent, untalented, ungifted children, without flair’ find it difficult to muster up the effort, when what is expected of them is fixed and ultimately, unlearnable.

Strangely, the negatives of praising intelligence and other fixed traits are not restricted to those who, as it were, lack it. In a landmark series of experiments on American 5th graders, researchers Claudia Mueller and Carol Dweck found that kids behaved very differently depending on the kinds of praise they received.

Children who were praised for their intelligence tended to avoid challenges. Preferring instead, easy tasks. They were also more interested in their competitive standing — how they measured up relative to others — than they were in learning how to improve their future performance.

By contrast, children who were praised for their effort showed the opposite trend. They preferred tasks that were challenging — tasks they would learn from. And children praised for effort were more interested in learning new strategies for success than they were in finding out how other children had performed.

Furthermore, children who were praised for their abilities were:

• More likely to give up after a failure

• More likely to perform poorly after a failure

• More likely to misrepresent how well they did on a task

In summary:

- When the children were praised for their ability, it made them focus on looking good instead of learning.

- When the children were praised for their intelligence, they learned to view their failures as evidence of stupidity.

Those who strive for excellence, value effort over intelligence.

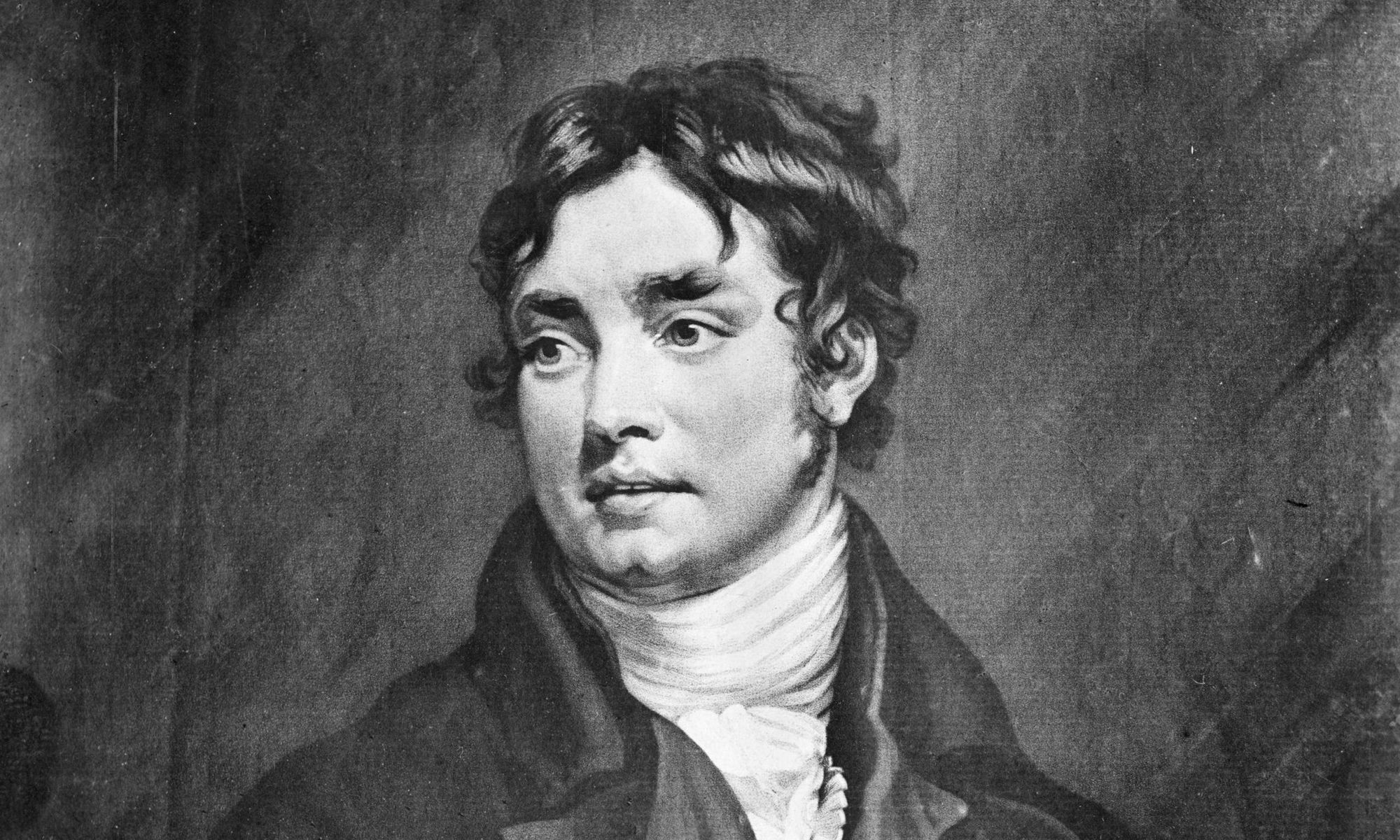

Coleridge’s Magnum Opus Technique

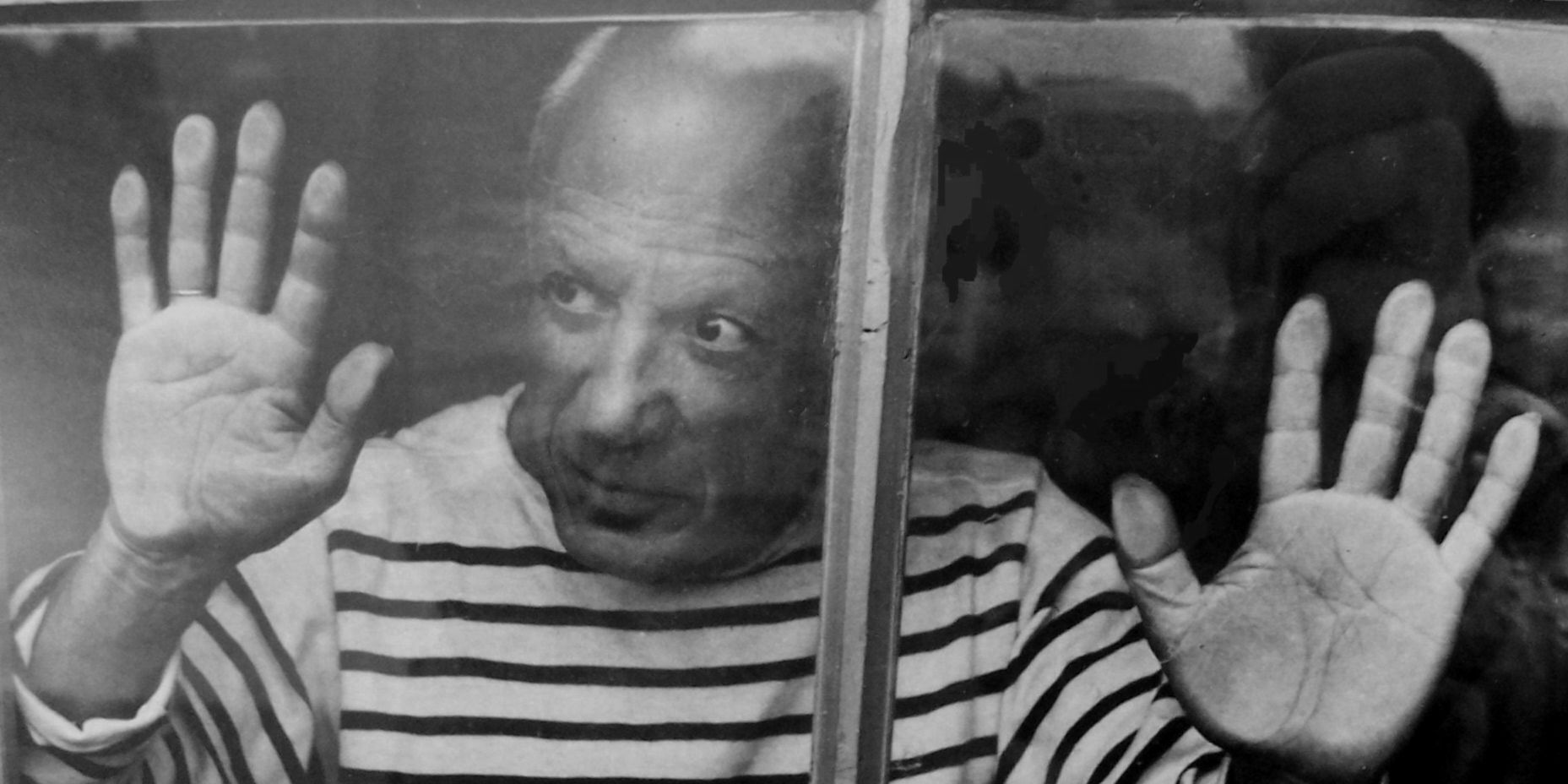

In 1973, Pablo Picasso, the most prolific artist of the 20th century, creator of an estimated 147,800 works of art, at the age of 92, shortly before his death, was interviewed by Michael Parkinson.

During the interview Parkinson asked Picasso to sketch a quick portrait of him. Picasso spent the next two minutes happily doing so. Upon seeing the positive reaction from the audience Parkinson asked Picasso ‘Out of interest, how much would this sketch sell for?’

With a smirk, Picasso answered ‘Around six thousand pounds.’

‘Six thousand pounds! How can something so quick be worth so much?’

To which Picasso replied:

Michael, this drawing did not take me two minutes, I’ve been working on it for over eighty years. *

Picasso understood that when the artist works on his art, he also works on himself; that at the end of an artist’s life (or after it) we tend to view his work as inseparable from himself; that his life’s work and his life are one and the same.

Painting is just another way of keeping a diary

– Pablo Picasso

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the poet, and philosopher had a similar approach to work. He set himself the goal of writing a Magnum Opus at the end of his life and everything up until then was just a rough draft.

The first draft of anything is shit.

– Ernest Hemingway

He viewed every piece of work he did, up until his Magnum Opus, as practice; as a chance to refine his ideas and learn from his mistakes.

Coleridge, not surprisingly, never did complete his Magnum Opus. But his Magnum Opus helped him to complete other works, by allowing him to fail. Many of his ‘rough drafts’ are now considered masterpieces.

There’s an old self-help saying ‘what would you attempt to do, if you knew you could not fail?’

What would you attempt to do, if everything up until your Magnum Opus, was just a rough draft?

Picasso’s Art Of Deduction

If you look at many master painters, from Picasso to Rembrandt, a trend you’ll sometimes notice is that early on in their careers, their paintings are what artists call ‘tight’ (invisible brush strokes/photorealistic) but as they progress their paintings become ‘loose’ (visible brush strokes/unrealistic).

Art is the elimination of the unnecessary

– Pablo Picasso

It’s as if they have come to terms with the impossibility of replicating reality as it is and instead spend their time highlighting only what they deem important about a particular scene. Their values on what good art is, shifts from ‘the quality of a painting is determined by the elements included’ to ‘the quality of a painting is determined by the elements eliminated.’

The Realistic Painter‘Completely true to nature!’ — what a lie:How could nature ever be constrained to a picture?The smallest bit of nature is infinite!And so he paints what he likes about it.And what does he like? He likes what he can paint!– Friedrich Nietzsche

Whether you’re describing a scene, painting a portrait, expressing an idea, or doing research for a film, you must surrender to the limitations of the form.

Striving for excellence, by definition, is the elimination of the unnecessary details that overburden perfectionists. You must surrender to the fact that in order to be successful at something, you must also be unsuccessful at something else. You cannot do it all.

Art is not like real life. In art we believe everything included is the result of the artist’s decision. If we watch a film and halfway through the main character dyes his hair, we assume it’s relevant to the story. Yet in life, people dye their hair all the time, and we don’t read into it.

Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

– Anton Chekhov

By trying to be all encompassing, by placing minor details next to major themes, you will dilute your message and give the unimportant a level of importance that is contrary to your own intentions.

Read: An Artists Attempt to Revolutionize Portrait Painting – A Personal Story by David Kassan

In short: eliminate the unnecessary.

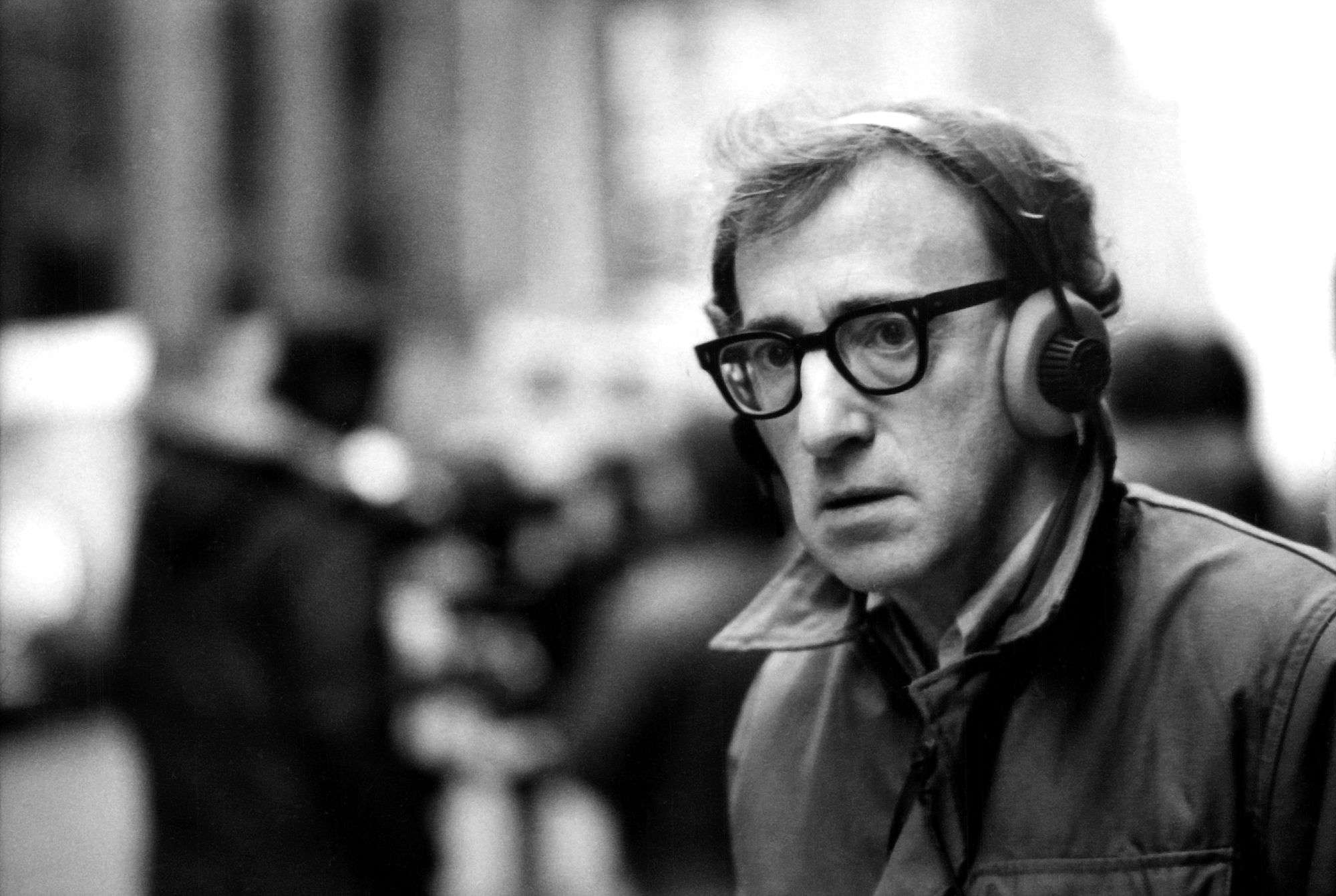

Woody Allen’s Quantity Theory

I get a good song for every 25 songs I write. So I’ve got to go through the process of writing 25 songs to get what I think is a good one.

– Gary Barlow

Woody Allen is a very different type of filmmaker to Stanley Kubrick, but no less revered as a genius.

His work output is astounding. Since he first began writing, directing and often starring in his own films, he has released no less than one per year (46 at time of writing). So far he has been nominated for the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award sixteen times and has won three times.

He, like Coleridge, is also hoping to make his masterpiece, his Magnum Opus, but believes that it’s more down to luck than excessive amounts of practice. He believes that if he keeps rolling the dice, eventually, he’ll win big. Incidentally, after a string of critical bombs, his 44th film, Midnight In Paris, turned out to be the highest grossing of his career.

‘I’ve been working on the quantity theory,’ he told Robert Weide in the 2011 HBO portrait Woody Allen: A Documentary.

I feel that if I keep making films and keep making them, every so often one will come out. And that’s exactly what happens.

Allen is not recommending you start releasing mounds of garbage into the world. His own career would never have lasted as long if he did that.

He still believes that every film he creates is high quality, but he understands that there are a million and one things that can happen between the initial idea and the finished product. Not only that, audiences are harder to predict than we might expect. Every year expensive Hollywood films, with teams of expert marketers, lose money.

Think back to Picasso and his 147,800 pieces of art. Without ever seeing any, just from the quantity alone, it would be reasonable to infer that there is a masterpiece somewhere amongst them. Many aspiring artists focus entirely on quality of their work and forget the element of luck that is required to land a hit.

Countless bestsellers were turned down by dozens of publishers, many top scriptwriters have written multiple of scripts that will never be read, many artists have produced thousands of work that will never be seen. Michelangelo was known for burning the drawings that he didn’t like.

Remember: people only remember the successes of successful people.

The more opportunities you take, the more chance you have of being lucky.

Conclusion

You may have noticed, I’m not a big fan of step-by-step guides and rigid formulas for success. While they may feel empowering to read, what successful artist has ever achieved acclaim from such a guide?

I think it is better, instead, to learn from the processes of other successful artists, because all successful artists at some point have done just that.

A caveat, however, that is often overlooked by people hoping to learn the processes of other successful artists is that at some point, those artists stopped looking to others, and made up their own process. This is an essential step.

To be great, you must create your own process.

“Absorb what is useful, Discard what is not, Add what is uniquely your own”

– Bruce Lee

The truth is, you may never be a bestselling author, a billionaire entrepreneur, a famous artist or a world renowned filmmaker. The odds are incredibly stacked incredibly you, even if you’re talented, and even if you have help from your family.

But the one thing you can take from all of these ideas, is that learning how to fail is not only the best insurance policy incase you never succeed, but also the best strategy, to ensure that you do.

It’s win/win.

So get failing.

* Steven Spielberg described Stanley Kubrick as ‘the best filmmaker who will ever live.’ I’m not in disagreement with this. His work is astonishing. I’m simply highlighting the (sometimes unnecessary) sacrifices perfectionism demands. You don’t have to be the best that will ever live at something, to be successful at it.

* Validity of Picasso and Parkinson story is disputable. (The idea behind it, is not.)

Further Resources for Overcoming Perfectionism

Pursuit Of Perfect by Tal Ben-Shahar

Tal Ben-Shahar taught the most successful course in Harvard’s history on positive psychology. He is a real authority on the subject of wellbeing and has personal experiences with perfectionism.

Mindset by Carol Dweck

Carol Dweck discusses the best mindsets needed to succeed. The premise of the book is about the difference between a ‘fixed’ mindset vs a ‘growth’ mindset. Essential reading.

Poke the Box by Seth Godin

Seth Godin discusses the quantity theory in depth. He has authored many successful books himself, and walks his talk.

On Becoming An Artist by Ellen Langer

Ellen Langer is a well leading psychologist specialising in positive psychology. This book is her own personal journey on becoming an artist with her psychological insights along the way.

The Stanley Kubrick Archives by Alison Castle

An amazing look at the work of Stanley Kubrick. An extremely interesting figure and a glimpse into the workings of one of the worlds biggest perfectionists.

Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey

This book is filled with the work habits of hundreds of authors, artists, and musicians. If you want to move past the romanticised version of creativity and see the hard work that is required to make lasting art, this book will help you do that.

The Six-Pillars of Self-Esteem by Nathaniel Branden

Branden is the foremost authority on all things self-esteem related. Legend has it Ayn Rand, who had a relationship with him, used him as the basis for some of her characters in Atlas Shrugged. This book is a classic.

This post is republished with permission of the original author.

This original can be found at ComfortPit.com

Jon Brooks

Jon Brooks is a Stoicism teacher and, crucially, practitioner. His Stoic meditations have accumulated thousands of listens, and he has created his own Stoic training program for modern-day Stoics.