Matt Karamazov • • 16 min read

The Lost History of Muslim Geniuses and the Truth About Terrorism

“In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart. I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death. I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever approaching thunder, which will destroy us too, I can feel the sufferings of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquility will return again.”

— Anne Frank “Diary of a Young Girl”

1006 A.D. — GIZA, EGYPT

An eighteen-year-old Egyptian teenager named Abu stares up at the night sky, beautifully illuminated before him, and he instantly, viscerally, perceives that he is witnessing something special.

Though he will live until age 73 and become incredibly successful in the eyes of his peers, there is something about that night sky that seems more important to him than the political struggles that he is taught about in school during the day.

He writes in his notebook:

“This spectacle was a large circular body, two and a half to three times as large as Venus. The sky was shining because of its light. The intensity of its light was a little more than a quarter of that of moonlight. It remained where it was and it moved daily with its zodiacal sign until the Sun was in sextile with it in Virgo, when it disappeared at once.”

Climbing down from the rooftop of his parent’s house, he wonders how many other people across the Muslim Empire have been fortunate enough to witness a celestial event of such grandeur and mystery.

Just 90 years later, Pope Urban II will declare the first crusade, millions of Abu’s fellow Muslims will be killed, and some of the greatest treasures of the Muslim world will be lost to history.

But on that rooftop in 1006, Abu ibn Ridwan will give precise-enough notations for astronomers in the United States a thousand years later to determine that he had witnessed a supernova.

TODAY

To review the history of violence is to be repeatedly astounded by the cruelty and waste of it all, and at times to be overcome with anger, disgust, and immeasurable sadness.

So says Harvard psychology professor Steven Pinker in his book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, which chronicles the decline of violence over the past several thousand years leading up to present day.

I’ve watched enough horror movies in my day to feel as though I can stomach anything, but Pinker’s book was one of the most uncomfortable, yet fruitful, reading experiences of my entire life. The vivid, excruciating detail of humanity’s violent outpourings is hard to deal with for more than a chapter or so at a time.

Although we do indeed live in the least violent period of history, it can seem today as if his book remains unfinished. That we can’t possibly learn from our previous indiscretions and become whole.

If you ask around, many people you might encounter in North America believe that there is more horrible violence to come.

Speaking as a Westerner, it’s helpful to remember in times like these that there have always been times like these.

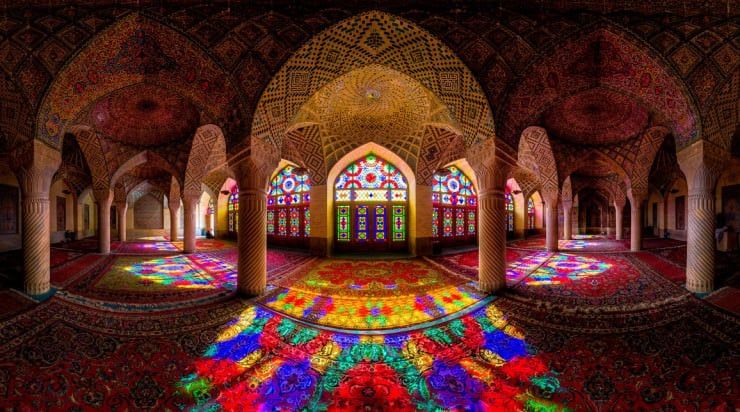

But that being said, there have been pockets of peace and prosperity hidden throughout the ancient and medieval world that have seemingly become lost to history.

Many people who live in war-torn areas today are the direct descendants of people who mostly found ways to live together in peace, and we can learn from the example of these latter people. We can reach back into history and let them teach us their lessons. We can create our own history, instead of being mindlessly shaped by it.

That idea—that we can retrieve lost lessons from history to create a better timeline moving forward—is the thesis behind Lost History: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Scientists, Thinkers, and Artists by Michael Hamilton Morgan.

LOST HISTORY

As its title suggests, Lost History chronicles the astonishing and oft-forgotten history of some of the most influential Muslim scientists, thinkers, and artists who ever lived.

The book discusses some Muslim thinkers who were undoubtedly polymaths—people proficient in wide-ranging areas of study who found time to write hundreds of books about their discoveries.

That’s not hundreds of books collectively; that’s hundreds of books EACH. You’ll meet one intellectual giant who wrote 200 books, another who wrote 361, and yet another who wrote close to 450.

To thinkers like Al-Khwarizmi and Omar Khayyam we owe things like algebra and algorithms, which enable today’s laptops and cell phones, our global economy, and feats of engineering like skyscrapers and the Space Shuttle.

To Al-Zahrawi, Maimonides, Ibn Sina, and Al-Razi we owe the origins of cardiology, antiseptics, and antibiotics; the first sutures and obstetric forceps; and the advent of mental hospitals and psychotherapy.

Far from being an apologist, Michael Hamilton Morgan doesn’t shy away from the fact that Muslims kill people too. Like all other human groups, they’ve been killing people for thousands of years; some of them still want to kill people; and some of them will end up killing people in the future.

But in his own words:

“Lost History shows global readers that many of the foundations of modern civilization rest in the Muslim past…It is a history that by the beginning of the 21st century had been forgotten, ignored, misunderstood, suppressed, or even re-written…

By writing ‘Lost History’, I hope to show not only the contributions of an old and rich civilization. I hope to show, as Caliph Al-Mamun concluded, that reason and faith can coexist: that by fully opening the mind and unleashing human creativity, many wonders, including peace, are possible.”

— Michael Hamilton Morgan

THE MESH OF CIVILIZATIONS

In a very real way, Muslim civilization is just as much a part of Western civilization as it is not.

When you look over the forthcoming list of Muslim contributions to world science, education, and art, it becomes increasingly self-evident that knowledge has no borders, and wisdom has no race or nationality.

In the end, technology is morally neutral. Atomic energy can either heat our cities or end our civilization. The internet can spread remarkable ideas or it can spread falsehoods. People of all civilizations, all religions, and all epochs have misused potentially beneficial technologies for nefarious ends.

Rockets allowed us to leave the Earth and explore the solar system, but their potential use in warfare prompted their original development.

Tracing their history, the rockets which inspired the American national anthem originated in China, were brought west by the Mongols, transformed by the Muslims, brought back by the Crusaders, brought west again by the Turks, used by the Indian resistance against the British, and then used on the Americans.

There are no stand-alone civilizations, and the complicated problems that plague us today aren’t going to be solved by one nation alone.

We can all benefit by slowing down, taking in the whole picture, and becoming well-informed about the races and civilizations that others may choose to automatically condemn.

As you will see, we are all responsible for what we are experiencing today.

With that end in mind, I’ve outlined some of the major advances that came out of the Muslim world during the middle ages.

If you’re not careful, looking at the accomplishments of these magnificent Muslim minds could easily make you feel as though you’ve wasted your life…

MAJOR MUSLIM CONTRIBUTIONS TO GLOBAL SOCIETY

Civilizations don’t advance in a vacuum, just as in our society there are no “self-made” men.

Progress occurs in leaps and bounds, stutters and spurts, and is led by iconoclastic thinkers who have summarily rejected the standard answers given by their societies to the problems of human existence.

It’s easy to become swept up in hysteria and not so easy to recognize the worth of those who we are led to believe are our enemies.

With that in mind, these are a few stunning examples—examples which are in danger of becoming lost to history—of Muslim contributions to global society:

*Abu Al-Battani (c. 858 – 929) calculated how long it takes for the Earth to make a complete revolution around the sun without telescopes or computers and was off by only fractions of a second. His major work was Book of Astronomical Tables, and he was often quoted by Copernicus.

*Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (c. 780 – 850) invented the algorithm and was one of the driving forces behind the adoption of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system throughout the Middle East.

*Paper technology imported from China by Muslims facilitated a level of public literacy that was unheard of at the time in mainland Europe (c. 973).

*The city of Baghdad, breathtakingly beautiful in its finest hour, had the first ever urban hospital and boasted 36 public libraries. No garbage was even allowed to remain within the city limits (c. 700).

*The Muslim city of Cordoba, which existed circa 1000 A.D., contained more books within its libraries than all of Europe at that time.

*Hasan Ibn Al-Haytham (c. 965 – 1040) calculated that twilight only occurs when the sun is 19 degrees below the horizon and used that idea to come close to gauging the depth of the atmosphere. He wrote more than 200 books dealing with optics, astronomy, mathematics, and visual perception, and is considered by many to be one of the fathers of empiricism.

*The Muslim world had hospitals, most of them free, hundreds of years before hospitals appeared in Europe (c. 700).

*Muslim astronomers calculated the diameter of the Earth and the distance around the equator 1,000 years before the Hubble telescope revealed that they were correct to 6 decimal places (Al-Biruni c.1000).

*Caliph Abu Al-Ma’mun (c. 786 – 833) gathered the greatest thinkers, books, and ideas of his time within the House of Wisdom in Baghdad—a place where Muslims, Jews, and Christians collaboratively pursued their intellectual aims in relative peace.

*Qutb al-Shirazi (c. 1236 – 1311) was a polymath and poet who first gave the correct explanation for the formation of a rainbow. He’s said to have been distinguished by his extensive breadth of knowledge, clever sense of humor, and indiscriminate generosity.

*Jabir ibn Hayyan (c. 721 – 815) was a polymath as well who is considered the father of early chemistry. He wrote more than 200 books and developed dozens of things, including ethanol. Interestingly, he disguised his writing in order to avoid being accused of heresy, and so the word “gibberish” is derived from his name.

*Abu Al-Kindi (c. 801 – 873) wrote 361 books (that we know of) on topics ranging from music, mathematics, and medicine to philosophy, astronomy, and chemistry. Someone like myself who damn near failed high school chemistry might find that impressive.

*Avicenna (c. 980 – 1037) wrote more than 300 medical books alone (450 in total) and introduced more than 700 drugs. He created the infrastructure for modern drug trials that were used 900 years later.

*Muhammad Al-Razi (c. 854 – 925) is one of the main people responsible for the idea that we are responsible for our own health, and he invented treatments for everything from colds and headaches to depression. The dude was even known for giving free medical treatment to the poor.

I think you get the idea.

The first time I read Lost History was about two years before writing this piece, and I’m still carried away by reverence for the astonishing accomplishments of the aforementioned founders of modern thought.

“We ought not to embarrassed about appreciating the truth and obtaining it from wherever it comes from, even if it comes from races distant and nations different from us. Nothing should be dearer to the seeker of truth than the truth itself, and there is no deterioration of the truth, nor belittling either of one who speaks it or conveys it.”

— Abu Al-Kindi

Their underlying kindness and insatiable love of learning itself is shockingly self-evident, and it makes you wonder how it is that the very same human societies which produce preeminent polymaths likewise produce pitiless psychopaths.

A DIFFERENT PATH

“My country is the whole world.”

— Virginia Woolf

It’s easy to forget how deeply brutality was once woven into the fabric of daily existence. Again in reference to Steven Pinker’s work, one of the reasons that violence offends most people’s sensibilities now is because it’s so much less common.

Indeed, towns in medieval France would sometimes actually “purchase” a condemned criminal from another town so that they could entertain their citizens with a public execution.

That would be just like the mayor of New York today buying the “rights” to a criminal from Buffalo, NY, and executing him publicly and violently in the middle of Times Square.

Could you even imagine such a thing happening anymore?

Yet this was commonplace in our not-too-distant past.

The bottom line is that a human being born today is less likely to die at the hands of another human being than at any other time in our history.

It’s tempting to believe that we’ve somehow “grown up,” but our battle against prejudice and ignorance must be renewed in every age. We have something to learn from benefactors like Caliph Abu Al-Mamun, who gathered together the greatest minds of his generation all in one place, for the singular purpose of advancing human knowledge.

Around the same time as Al-Mamun, in the Christian world, we were burning “witches.”

In the interest of intellectual honesty, the High Middle Ages saw a resurgence in the contributions of European thinkers, many of them aided by translation of their Islamic predecessor’s treatises. On the whole, however, the Islamic world was a beacon of scientific light compared to the narrowly superstitious Europeans who dominated that period.

Pinker relates the story of an old woman in Scotland during the Middle Ages who broke HER leg at approximately the same time a local cat broke ITS leg. Since the townspeople never saw the woman and the cat in the same room, they assumed that the old woman was a witch, and she was burned to death.

More recently, we violently persecuted Alan Turing—the man who broke the Nazi’s “Enigma” code and hastened their defeat—for being gay.

We wouldn’t have the internet or computers without Turing, and yet the British government ordered him to be chemically castrated as punishment for his sexual orientation. He killed himself in 1952 at age 42.

I will interject here that this is not a reason to engage in self-hate. Rather, I believe we need to forgive ourselves for our indiscretions before we can forgive others for theirs.

What we need is to shine a light on ourselves and take responsibility for our part in directing humanity’s future.

But which is more difficult? Forgiving ourselves or forgiving others?

Where the Muslim world is concerned, there is a lot of anger and sadness felt by people in the West. We’re not ready to forgive their whole civilization for the actions of a small psychopathic subsection of their society.

Understanding breeds forgiveness, and understanding the lost history of these Muslim thinkers, scientists and artists is one of the most powerful ways I know of to begin the process of healing.

THE MAKING OF A TERRORIST

“If it holds that Islam is only what [the majority of] its adherents interpret it to be, then it is currently a religion of peace.”

— Maajid Nawaz

Terrorism, inflicted by anyone, is a plague on human society and a legitimate danger to human flourishing.

Men and women of science, art, and philosophy have traditionally scorned the practice, and it’s my contention that anyone who is a genuine lover of wisdom has no patience for such trifles.

Yet, violence has been a constant throughout human history, including during the time when these great Muslim scientists were living and working.

The violence in the Christian Bible alone is staggering.

For instance, there are 600 passages about killing others, more than 1,000 times when God gives a direct command to kill others, 1.2 million deaths as a result of mass killings in the Bible… and today, Sunday School children now draw pictures of the perpetrators in crayon.

Lest you think mass violence is just a Major Organized Religion thing, between 1440 and 1524 AD, the Aztecs sacrificed 40 people per day, for a total of around 1.2 million.

Even atheistic states such as Stalinist Russia have deaths to answer for, and while the exact numbers will never be certain, communist leaders of the USSR were responsible for no fewer than 15 million deaths in the 20th century.

And if you really want to erase any doubt as to the culpability of the West in encouraging and spreading violence, the death toll that the Crusaders racked up when they invaded the Middle East reached 1.7 million. Some estimates place the figure even higher at around 3 million, especially since battle deaths at that time would have been underreported.

Today, 10 percent of poll respondents in the Middle East say that suicide bombing is “sometimes justified,” compared with 24 percent of Americans who say that the targeting of civilians by military forces during wartime is “sometimes justified.”

In Islam and the Future of Tolerance: A Dialogue, Sam Harris works with Maajid Nawaz to identify four major pieces that have to be in place in order for a young man (most violence is perpetrated by men between the age of 20-30) to turn to terrorism.

These are:

#1: Grievance Narrative, Real or Perceived

Our potential terrorist needs to have a reason to hate Western civilization. There needs to be a history of (real or imagined) oppression or marginalization that burns in this young man’s mind and lead him to seek vengeance.

#2: Identity Crisis

The answers to the problem of human existence that his society offers him have to be insufficient. He has to feel as if there is something more that he can become; some incompleteness within him that he needs to remedy. He searches desperately for the answers to the questions posed by his anguished searching.

#3: Charismatic Recruiters

There needs to be a role model for our potential terrorist that he looks up to, and who advocates violence on a grand scale. Terrorists become terrorists because they are recruited by someone attractive and magnetic, who is able to offer them a way out.

#4: Ideological Dogma

The final piece is the distortion of Islam’s message that is presented to the young man as inviolable truth. While not completely a religion of violence, it lends itself rather well to extremist interpretations. Victory for Allah is presented as destiny, and our disaffected potential terrorist begins to believe that ultimate victory is inevitable, and that he will benefit by becoming a part of it. Anyone who doubts the murderous power of ideology need only look to the 20th century to note that three ideologically possessed leaders—Hitler, Stalin, and Mao—caused the deaths of ~80+ million people.

These four factors combine to create a recipe for the construction of terrorists. It’s useful to ponder these items to understand how normal human beings can be transformed into ideological murderers.

Part of the bargain of being alive is taking the chance of dying a premature or painful death, but the presence of terrorism in our world exacerbates those risks tremendously.

In contrast, the great Muslim thinkers of old were lovers of knowledge and wisdom, and that’s what we need to support.

THE REAL COSTS OF TERRORISM

Nothing in our discussion so far is meant to excuse terrorism, deny its existence or impact on the geopolitical landscape of today, or downplay the potential dangers that radical Islamism poses to our continued safe existence.

But I think we would do well to balance our genuine concerns about global jihadism with an appreciation of the Muslim world’s contributions to Western society, as well as a recognition that the majority of Muslims worldwide do not support or contribute to terrorism.

Simply put, there remains an unexamined fear surrounding the real costs of terrorism that is worth going into intellectually rather than emotionally.

For example, it would help to know that in every year except 1995 and 2001, more Americans have been killed by peanut allergies (13), bee stings (53), lightning (51), deer (200), and (seriously) ‘ignition or melting of nightwear’ (5) than by terrorist attacks.

Furthermore, no small terrorist organization has ever taken over a state, and 94 percent of them fail to achieve ANY of their strategic aims. Most terrorist groups fail die out within a couple decades of emerging.

These examples are sobering and allow us to gain a more realistic understanding of what terrorists have managed to do to date—i.e. not nearly as much as what most people think. Clear thinking and reasoned action, rathe than fear-driven assumptions, are greatly needed in this area.

Nonetheless, it is important not to understate the potential threat posed by terrorist groups, especially in a world with hyper-dangerous weapons which could occasion the extinction of our species. Our prognosticative capabilities are limited, but we can reasonably assume that groups like ISIS would kill all non-believers if they could. We have every reason and right to defend ourselves against the legitimate threat of terrorism that still faces the Western world, but the heuristic that tells us that “no Muslim should be trusted” will not be helpful.

“If your intention is to stop terrorism, do not try to blame the whole population of Muslims for it because it cannot stop terrorism. It will radicalize more terrorists.”

— Malala Yousafzai

CONCLUSION

Does humankind learn? Or do people simply forget and rediscover?

At every stage of history, there have been social commentators who insist that we have never had it so bad. But you can see from what I’ve presented that that just isn’t true.

As I mentioned previously, a human born today is less likely to die at the hands of another human than at any prior point in history.

Terrorism is surely a scourge in the modern world, but its actual impact is often overblown, and in all likelihood it won’t plague us forever. We mustn’t allow ourselves to live in fear, and we mustn’t use our fear of terrorism as a justification for alienating the 1.5 billion Muslims in our world and forgetting about the Muslim world’s important contributions to human progress.

As free individuals living in a human society, we can change our destiny at any moment.

Indeed, we MUST choose our future, since as Jean-Paul Sartre explained, we are condemned to be free. Our burden of responsibility charges us with learning from our peaceful and fruitful coexistence in the past, as well as taking some control of our destiny and making the world a saner place for our children.

In the brief season of life, the first responsibility is to live, and to enrich life in oneself and others. This, we can say, the Muslim scientists and thinkers of old have done for us.

As it says in The Good Book: A Humanist Bible, by A.C. Grayling:

“Those who first set themselves to discover nature’s secrets and designs, fearlessly opposing mankind’s early ignorance, deserve our praise.”

Indeed, we can praise their accomplishments, condemn the actions of the minority of Muslims who support terrorist ideologies, and get to the real business at hand, which is living itself.

We can extend our search for truth to wherever we venture to look for it, keeping in mind the realization that no idea is above scrutiny, and no people are beneath dignity.

Without delegitimizing modern concerns about the spread of jihadism and Islamism, we should aim to remember the Muslim world’s many important contributions to our global community, as well as the hundreds of millions of peaceful Muslims who wish to live harmoniously with the rest of the world.

It is my hope and the hope of many, including King Abdullah II of Jordan, who wrote the foreword to Lost History, that: “Just as our pasts have intertwined in constructive ways, so too can our futures.”

All the best,

Matt Karamazov

Further Study:

Lost History: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Scientists, Thinkers, and Artists by Michael Hamilton Morgan

This book fills a significant void and is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the major role the Muslims played in influencing modern society. West and East are mutually interdependent, and Morgan shows that we can take what worked in the past and build a more peaceful future.