Jack E Othon • • 22 min read

Merrily the Mount Snow Flies — A Tale of Life, Death, and Cosmic Wonder

January 21st, 2012.

I remember the date because Olivia said it was her six-month birthday. Neither of us thought we would end it on snow-covered mountain passes that seemed to slope up at damn-near-90-degree angles in whiteout conditions with a severely depleted gas supply and the cold truth of the matter, that we weren’t exactly where we were supposed to be, and didn’t know how far from supposed-to-be we exactly were. But the day had started out pleasantly enough.

We had arrived at the yurt of Sacred Hoop Ministries in Woodland Park, Colorado at promptly 9 o’clock in the morning. This was unusual, because Olivia was never on time for anything, and she was the one driving. We gathered with the others in a semi-circle around the wood-burning stove, nesting in our blankets and pillows as we prepared for the day-long Introduction to Shamanic Journeying class.

Mostly I stared up at the sky through the circular opening at the center of the yurt while Olivia and the others absorbed the information about the lower world and power animals, and the upper world and spirit guides. I had heard it all before, but I was politely attentive, all the same. The secret is you have to die a little to reach the gold; detach from your body just enough to fly away, but keep a tight enough grip to return to tell the tale.

I missed my mother, a shamanic practitioner who had recently moved cross-country, and that was perhaps my main reason for being there. The gold-brown animal skins and orange-turquoise-red indigenous ornaments reminded me of her and her constant beckon to return to our Mexican-Apache roots. Even at 24, it was surprising how strongly that instinctual yearning for the womb-void still called in me. Olivia, who was a decade and a half older than me, reminded me of my mother in a distant way.

We ate lunch in a little graveyard nestled in the mountain pines. I remember wispy green grasses and delicate wildflowers that weren’t in bloom that time of year. The truth was probably closer to snow remnants—the crusty grayish kind that are dirty beyond beauty, but still cling to the frosty air in the pockets of shade where the sun can’t shine. Spring sang in my mind while the dead of winter lay in fragments all around me. Strange, the kinds of tricks the memory plays.

I don’t remember what else we talked about—I mean, we were telling each other secrets, but after a while all the secrets blend into each other, and it’s hard to remember which ones are the deepest, most intimate secrets; there’s just the secret of the other’s soul, now known only to you. But at one point Olivia told me, “I feel like your soul is special. And I know, yeah, everyone’s unique, everyone’s special. But no, that’s not what I mean. I feel like you’re really special.” And we didn’t make eye contact but I really glowed then.

We didn’t know each other well enough for her to know how much the once-dead piece inside of me needed to hear those words. She probably doesn’t remember saying it. But I think about it almost every day. Yes, funny the way the memory plays.

We spent the afternoon dancing in and out of the spirit world, taking whichever openings our imaginations could find. I met my power animal again, and I told everyone. Olivia met hers too, but she kept it to herself. I met my spirit guide again, and I said so to the entire room. Olivia met hers too, but she kept it to herself. She had a way of not saying a word, but telling everything. Typical Cancer.

At 5 o’clock we took our leave and stopped for dinner at a small Italian-ish restaurant before continuing up the mountain toward Cottonwood Hot Springs in Buena Vista, where we had a double room booked. Somewhere between dinner and getting back in the car, Olivia finally broke down and started talking about Ethan, her best friend who had just died unexpectedly. I was surprised that she had made it that far before she needed to talk about him, and I did my best to comfort her while I listened to the sad tale of failed romance and a friendship of unrequited love, about which Olivia felt not-quite-guilty but less-than-good. With both of our attentions fixed on Olivia’s emotional outpouring, she pulled her Jeep onto the highway and drove into the starry alpine night.

What a pair we made, Olivia in the hushed wake of death while my star ascended, barely entering the prime of life and only a semester away from college graduation. As the world opened before me, a big piece of Olivia’s had come to a final close.

We were looking for a T-intersection, she said, and then we would have to turn left. We would be there in an hour and a half, by about 8:30 P.M. Puffing on a chillum as I observed the scenery from the passenger seat, I absently reflected on how much the road resembled one from a past aimless mountain drive, when an ex-boyfriend and I had pulled over in the wilderness to turn back home and heard ghostly screaming echoing through the forest. I tried to focus on Olivia’s voice, but found my eyes picking out movements between the darkened trees, where all was still.

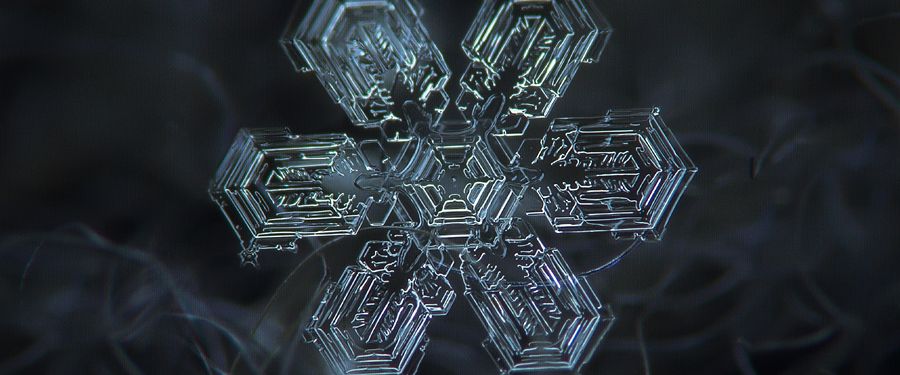

We came to a T-intersection and dutifully turned left, pausing at a convenience store a few miles after the turn. Olivia wanted to look at a map; she said the intersection hadn’t looked the way she remembered it, but could make no sense of the obscure lines and numbers that people were meant to navigate by, in days long past. I was in the cruise-control mental state of not-knowing-the-way to where-we-were-going, so I spent my time scoffing at the fine snowflakes misting the air. There had been no reports for snow that night, down in the valley (and I should know, because I checked), so with my lowland technological superiority I tossed my head at the frozen water, telling it to get its kicks in while it could. Soon, I said, it would amount to nothing.

The road had just begun to slope at an angle that was the stuff of nightmares when the storm stopped playing coy.

The first signs of trouble were the extended pauses between Olivia’s words as she began to focus her energy on her driving. The second came when we could actually hear the Radiohead album that was playing. The third sign was when the musical silence was interrupted only by Olivia’s occasional, “This is bad. This is really bad.”

And really bad, it was. The low beams illuminated only the most immediate small circle of road, which was quickly disappearing beneath a fresh layer of vanilla frosting, slathered thick on our deathday cake. The high beams were less help, only serving to brighten the whitewall of hyperspace light-speed snowflake galaxies, so that one couldn’t be truly sure one hadn’t been stricken by a sudden case of Saramago white blindness.

Tap, tap, tap, whispered the snowflakes to our windshield, a secret they couldn’t keep to themselves. Tap, tap, tap, Death tips his cap, the call of the quiet banshee bird. Death’s invitation is so often a chaotic, cacophonous thing, yet this gentle fall of frozen cherry blossoms made a lovesick song out of even his shrillest cry.

I don’t know why I was so maddeningly calm. I think mostly I was just happy not to be Olivia. Hers was the unenviable task of keeping the Jeep, and us along with it, from plunging over the mountainside down toward an indistinguishable whitish death. My job was only to tell her where the road ended on the passenger side, so she could stay on it. The simplicity of my role gave me a peace of mind granted only to the most singularly-focused of organisms on this big, blue Earth, and I was happy to partake in it.

Of course, if I stopped to think about it, given the thickness of the snow on the road and the sheer angle of the ground beneath our tires, exacerbated by the laws of physics and the forces of gravity, multiplied by how little faith I had in the Jeep brand, a sort of all-consuming slow panic would begin to envelop my brain. Somewhere in an especially evil part of my mind was contained the knowledge that we were defying fate by driving up the deck of the sinking Titanic in a bloody blizzard with only our sheer-brazen-gall keeping us alive.

And when combined with the fact that there was nowhere to turn around on this inconceivable hellspawn of a narrow highway, and that we had no choice but to continue climbing, because stopping would provoke a precarious stuckness at best, and a deadly backwards end-over-end plummet at worst—and despite the fact that once on the other side of this accursed rocky protrusion we would have no choice but to descend, whether our tires maintained contact with the road or not, just because Sir Isaac Newton said it must be so… then yes, I suppose there was something like fear presented to me in those moments.

But it was Olivia’s job to worry about that, so I preferred not to think about it, and I focused only on keeping a lookout for the road to end and oblivion to begin.

And anyway, I wasn’t really leaving all the work to Olivia—I’m not that goddamn selfish. My true task was to help her stay calm in a fucking-stupid-intense situation so that she could continue to maintain a high level of fucking-stupid-intense concentration on her driving, and the best way to keep someone else calm is to stay calm yourself. And staying calm in the face of fucking-stupid-intense death requires one to be essentially intensely fucking stupid, at least for a time.

I began to chatter away in a tone of such carefree optimism that Olivia probably would have been well within her rights to punch me in the face. Luckily for me, she was too frightened to be annoyed. I chit-chit-chattered over the squeak-squelch-crunch of tire snow. Chit-chit-chattered over every quick-caught breath and half-muttered curse escaping pursed red lips. Chit-chit-chattered over the sticky grind of white knuckles against a black leather steering wheel cover. A merry laugh at the sight of vertical headlights sliding down toward us, imagining a mirror image of merriment and fright as the approaching vehicle began to pass. My right foot was the only sign of my body’s worry, pressing against the floor as it willed the Jeep over every slope and mountain crest.

What I was working so hard to ignore was how much that unconscious act betrayed Everything beneath the surface of my calm.

When I was nine years old, my favorite movie was The Crow. In one scene, the villain holds a cemetery snow globe, telling his sister that their father gave it to him on his fifth birthday. “‘Your childhood’s over the moment you know you’re going to die,'” his father had said.

For me, that moment had come when I was twenty-one. As I sat in the crowded coach cabin of an American Airlines flight from Colorado Springs to San Antonio, I became acutely aware of the miles of air between me and the ground. Though I was a seasoned airport rat, averaging between 2-4 flights every year since I was eight to visit my father, the danger had never impacted me the way it did on this occasion. It was as though I had been lulled into a sterile dream, where everything ran on time exactly as it should and death only happened to people in movies.

Except that it didn’t, I realized. I could die at any time. Like, I could die —> right now. Death wasn’t supposed to happen—I was young and had my whole life ahead of me, and so on. But death doesn’t care; it’ll take anyone. I had never known such an impersonal force before, and it shook me to my core.

My flirtation with death was years in the making. I was 12 the first time I attempted suicide. No one knew; I just went to bed with a stomachache and the knowledge that it’s a lot harder to die than people might think.

I continued to push against that veil through my teens, first indirectly—dropping knives into a sink full of soapy water and fishing for them with my bare hands, “slipping” in the shower, walking alone down dark urban alleys, dating guys I was always a little afraid of, deliberately leaving my seatbelt off every time I got into the car. After a couple of years with no real progress, I took a more direct approach, first banging a rock into my rib cage, then experimenting with ever-harder substances, and finally cutting myself with knives and razors, pressing harder every time just to see how deep I would have to cut to draw enough blood to die. (It’s really deep, FYI, and it hurts like a bitch—don’t do it.)

It was the mundanity, I know now. I thought of the days dragging on, every one similar to the last, forever and ever all across the world and probably the entire known universe times infinity. Millions of humans had done the same basic things in the past—eat, sleep, work, fuck—and for all I knew, millions more would continue to do the same-old-same-old for millenia into the future.

There was nothing new. Nothing ever happened. The clock and calendar automate our lives and we all do what they expect of us: wake up, force yourself to eat, go somewhere you’re expected to show up and be there far longer than you want, then go home and find a way to distract yourself for the few precious hours that are all yours from the fact that the vast majority of your life doesn’t even belong to you. Go to sleep. Repeat.

When I tried to explain my self-destructive impulses to myself, I decided it was self-loathing. I never truly hated myself, though, that’s the thing.

I just wanted to PIERCE THE VEIL!—

to touch something real—

to get away from this sterile, muted, plastic TV-land where death and pain and love and passion are for >actors< and the rest of us avoid them like the plague.

Don’t catch the feels! — They’re an incurable disease.

So, what changed when I was twenty-one? If I wanted to die so bad for so long, why the sudden fear when I discovered how real the possibility was?

Well, a lot of things, I guess. I had moved out of my mom’s house a couple years before. For the first time in my life, I’d had the freedom to determine the course of my life. I had the freedom to shake mundanity in more creative and decidedly less-self-destructive ways. I had been so restricted before that it seemed my death was the only thing I had control over. Dying seemed the only rebellion I had to mount. It was the ultimate rule to break, and I was determined to stick my middle finger right in the face of every kind of authority life put in my way. Couldn’t expect anything less from the kid whose first complete sentence was, “You’re not the boss of me!”

Sitting on that plane, though, with no control over whether the craft would plummet into the ground or maintain its supposed-to course, Death was the one authority that could never really be fooled, and I really knew it then. You can laugh in Death’s face all the way to your grave, but you still have to lie there, in the end.

And what else? Since my suicidal years, I had fallen in love.

I had seen the beauty of the sunlight glistening in the hair of a redheaded boy.

>> I had discovered THE BEATLES! <<

—> —> I had picked wild raspberries and seen the silver-sheened full moon making love to sultry pines in the rugged Colorado mountains after I emerged rain-soaked from the leaky tent where my companions stayed sleeping, knowing the secret was meant just for me. <— <—

XX – // I had fallen into the darkness of another human and choked my way past his white knuckles clenched round my throat, battling the booze in his breath toward an understanding of what it really means to lose oneself. MURDER would have been the word for what almost happened to me, no less tragic and only slightly more socially acceptable than suicide, depending on what I was wearing and how many drinks I had consumed that night. \\ – XX

As hard as it is to die, it’s also incredibly easy. It can happen at any time. You can miss a step on the staircase in your home, touch a faulty wire, swallow down the wrong pipe, get lost on a mountain highway in a blizzard (as a random example), walk down the sidewalk and get struck by a stray car or bullet or rogue spacecraft toilet seat. You can die just because someone else decides to end you, and they don’t really even need a good reason.

Death is the one thing we never seem to see in our sterile Western culture, and yet it’s omnipresent.

Every day is a roll of the dice, and every one that we survive is but a delicate step in the lifelong courtship dance with oblivion.

Eventually we all accept Death’s hand. But that day on the plane was not my time, nor that night in the alcoholic’s bed, nor this crazy fucking snowblind road trip from hell.

So, why was I so calm in this blizzard? When I heard Death whispering my name as snowflakes echoed the tap of its skeleton fingers against my frosty window, I recognized the voice of my old friend.

At last the road leveled out somewhat, and the snow did not pack itself on the pavement with such insistent thickness, but was content to merely dance before the Jeep’s headlights in the hypnotic shapes of snow snakes. This optic spectacle posed a particular danger to our sleep-deprived driver, whose resilience was now well worn by the crash of a post-adrenaline episode. Luckily for her, the journey was ready to provide more incentives to keep our nervous systems on high alert.

“We’re almost out of gas,” Olivia said, “and I don’t know where we are. I filled up my tank before we left the Springs. I should’ve been able to make it all the way to Buena Vista and back on only a quarter of a tank, but now we’ve used more than three quarters and I don’t know where we are. None of this looks familiar. It shouldn’t be taking us this long to get there, even with the snow.”

We hadn’t passed a gas station in over an hour. Neither of us could get a cell signal, and even if we could, the highway seemed reluctant to either reveal its name or give an indication of where we were on it. Silently I began to prepare myself for a long, cold night in the Jeep on the side of the highway in the middle of a mountain winter storm. A little panic started to peck away at the cloud of my calm. We didn’t have any blankets, or any food.

Not that we were in much danger of freezing or starving to death, but try telling that to your instinct-saturated cellular memory. No, we would not have died from only one night of strandedness—but we would have been very uncomfortable, and the hassle of resuming a state of normalcy the next day would have been terribly inconvenient. Of course, the voice of reason is never an especially loud one in moments like this, and we had just sort-of-almost-died. Still, somewhere on the outskirts of my awareness, I felt my primal ancestors roll their eyes in disgust.

Within a few miles a spark of life came to our mobile phones, and we handled the devices delicately, as though the slightest breeze would snuff the precious singular bars of signal. Olivia immediately called the desk clerk at the inn, who had been expecting us. She quickly explained the situation to him. He wasn’t much help—not that we could have expected him to be, and we weren’t much at helping him help us.

“What did he say?”

“He said to follow the highway until we came to the T-intersection, then take a left.”

“We did that.”

“Yeah, that’s what I told him. He didn’t know what else to tell us. He just said he’ll wait until midnight, and if we’re not there by then, he’ll leave the key to our room.”

We rode on in silence for several minutes. Olivia was beginning to grow tense, and at long last, so was I. The whole situation was just fucking stupid—the snow, the road, the gas, the phone—and with the sequence of simultaneous brands of perfect-storm-bad-luck, it seemed to be building itself up to some stupid horrible horror-movie-climax.

The wheel of fate turns, finds your name, and aligns your life with a river of karma trickling down from the cosmic peach pit of the known juicy universe. A shiver of life runs deep red up the spine, activating an electrical-rush-of-adrenaline spike. After such a swelling build, the only thing that would have been worse than a climax of awful-meets-sublime elemental death would have been no climax at all.

The Jeep’s headlights caught a flash of green; after miles of black and white the sign caught our attention easily. COLO SPGS: code for homeward, at the next left. We passed it. The highway fell from the middle of the mountain to hug against the side of its slope when I glimpsed a faint orange glow in the sky somewhere ahead of us. Growing up in the city taught me that that was the unmistakable sign of civilization—but there was no telling how far away the lights were. A glimmer of hope jumped up inside of me. Before I could communicate my optimism, Olivia slowly applied the brake and brought the Jeep to a halt, her head tossed back like a horse that was spooked—a very tired horse.

“I think we should turn back,” she said. “None of this looks familiar, and I’m really worried we’re going to run out of gas if we keep going. If we head back towards the Springs, we might have enough gas to get us to the next gas station.”

My heart sank a bit.

“I think if we keep going a little further, we might run into a town,” I offered.

“Yeah, but these mountain towns are so small, and even if we run into some houses, there might not be a gas station that we could find. I’d rather not waste the gas and just head back to where we know we have a chance of finding something.”

I sighed quietly, but knew Olivia’s logic was right. Yet what a disappointment, to have driven so hard out of the gaping-jaws-of-death, only to return home in defeat, with nothing to show for our trouble other than money lost on the fuel. Olivia found a safe place to turn the Jeep around, and we doubled back until we found the sign that pointed the way home. My heart yearned uncomfortably for the fulfillment of journey’s end, the anticipation of a moment lost, an experiential craving unsatisfied—like reaching out for your lover in the dark, and finding only a cold, vacant pillow. Olivia must have known the same dull ache. As we turned right off the highway, she slowed the vehicle again.

“This would probably be a good place to call the guy at the inn,” she said. “Maybe he can tell where we are from here.”

We sat in the middle of the road—we hadn’t seen anyone for hours, so fuck it—while I called the desk clerk. I didn’t see the use, now that the decision had been made; but Olivia and I were both growing frustrated, so I went along, just to appease her. When the clerk answered, I gave him an awkward description of where we roughly were. We came to a sign, I explained lamely, and turned right.

“No, no, you should have turned left,” he said, though he sounded uncertain. “Did you come to the T-intersection?”

“We did that already,” I said.

“What did he say?”

“He said we should’ve come to the T and taken a left.”

“We did that already.”

“That’s what I just told him.”

“Let me talk to him.” Olivia reached for the phone. I listened as she repeated a description of our recent navigational maneuvers and subsequent vague location. “We passed a sign and then we turned right.” A pause while she listened. “No, we did that already.” After a couple more minutes of discourse, Olivia uttered a few defeated “okays” and hung up the phone.

“What did he say?” I ventured pessimistically, mostly for conversational purposes.

“He said we should’ve gotten there thirty minutes after we turned left at the T. But it’s been hours. He has no idea where we are. He just said he’ll wait a little longer in case we figure it out.”

She let out a frustrated sigh and buried her face in her hands. Even her curls looked tired and defeated. An irrational part of me was uncomfortable with the fact that we were still parked in the middle of the road. I looked out the window at the blackness around us, at a loss for ways to make the situation better. I lit a cigarette. Olivia did the same. We puffed in silence for a few moments, tapping our cigarettes on the edges of the cracked windows to drop the ashes as the CD ended and restarted for the third or fourth time since we started ignoring it.

“Let’s turn around and keep following the highway for a few more minutes,” Olivia finally said. I shrugged, completely indifferent. I just wanted this night to be over already.

Olivia pulled the Jeep around and the headlights illuminated a green sign at the top of the T-intersection: BUENA VISTA 16, with an arrow pointing to the left.

In all my days of living, I’ve never seen an arrow so resemble a middle finger, neither before nor since. But if that sign had a face, I would have kissed it.

“Ooohhhhhh,” we both sang. Facepalm. The goddamn T-intersection. Three guesses on which direction we turned.

I used to gauge the time spent with Olivia by how raw my throat was after so-many-hours-of-talking and so-many-American-Spirit-cigarettes-chain-smoked to replace the meals missed by the stomach while the mouth was preoccupied with words and laughter. By the time the Jeep limped into the parking lot of the Cottonwood Hot Springs Inn & Spa, we had exceeded our vocal limits three times over. It was 12:30 A.M.—five and a half hours after we left Woodland Park.

The desk clerk was still at his post when we rolled in. Apparently, he had been worried about us. Before he left, he pulled out his map to help us figure out what the hell had just happened to us. The sign at the T-intersection had pointed towards Buena Vista, to the left, and Fairplay, to the right, en-route to Deckers, a hundred-something miles away—the way we had come from. As it turned out, Olivia had turned onto the wrong highway when we pulled out of the restaurant parking lot, and neither of us had any clue that we were taking the extensive scenic route through a treacherous Jeep-eating mountain pass. Lucky for us, the detour looped us around to where-we-were-supposed-to-be, rather than taking us away to somewhere-else-entirely. We all roared with laughter at the epic fail of our navigational skills, the laugh of those who have narrowly avoided disaster and come out of it a little crazy. Well, Olivia and I laughed, anyway. The desk clerk chuckled quietly to himself and shook his head.

Up in our room, we sat on our beds staring at the Himalayan rock salt lamp and digesting our experience. My body was tired but my brain was wired.

“I bet you’re exhausted,” I said to Olivia. “Did you just want to go to sleep?” Despite my prior hot springs yearning, I wasn’t too reluctant to retire to the warmth and comfort of a cozy bed—the soaking pools were outdoors and there was still a blizzard on, after all.

“Fuck no,” Olivia said. “After all that, we are getting in those damn hot springs! I don’t care how cold it is.”

“Me neither!” I said, and started to dig in my bag for my swimsuit. “But still… it is going to suck.”

“Yeah…” Olivia conceded.

And it did. But only as long as we were running through blowing snow and frozen air that packed a wind chill well-below-zero in naught but our bathing suits. The howling west wind that had teased us from outside the Jeep now licked at our bare skin, tasting the living flesh previously denied its freezing embrace. Once we were in the water, it wasn’t so bad, and we quickly migrated from the coolest of the pools to the hottest. Besides a young make-out couple, we had the place almost completely to ourselves, and we soon ran them off.

Up at the top pool, I floated on my back and looked up at the sky. The wind was still blowing snow, but the clouds had cleared and the stars were out. Mountain stars—among the brightest in the world. The Milky Way smiled down at us from the midnight sky, shining universal benevolence down in the form of a million billion twinkling stars. I didn’t have to wait too long before I saw a shooting one. Olivia saw a few herself. She said she had asked Ethan to send her shooting stars, to let her know he was doing alright, wherever he was.

I let the hot mineral water cradle me, and I did my best to hug it back. Snowflakes crashed into my face, tap, tap, tap, and were pulverized instantly by my superior body temperature. It was the most peaceful violent death in all of existence, and it tickled. I remembered my mother giving me round-cheeked butterfly kisses when I was a child.

As I floated, weightless, I reflected on how serene I felt, at the end of a long, life-affirming survival struggle with the chaos-of-winter still blowing all around me,

colliding with my skin as I

demurely lifted a limb

to cool when the comfort

of the heat was too much.

Within every near-death experience lies the opportunity for a spiritual rebirth, and here I was, curled in the primal ooze of the infant cosmos, an ancient consciousness waiting to be reborn in the hip, modern world of techno-instincts and concrete forests. No virtual simulation could recreate my poignant sense of aliveness. No techno-fail could come close to the experience of staring into the eyes of one’s own death, and then into the face of the eternal, infinite universe, ready to open her womb and swallow us whole again.

The end of the road I had watched for so vigilantly had really been the end of the world, the end of my life, the end of the ego identification with the human once known as Jack, and perhaps by other names in lifetimes past. My spiritual dismemberment could have come then, as soul was ripped from shattered body, the clay crushed and removed from the ever-turning wheel.

Yet I remained, not outwardly changed from my experience, but inwardly no longer the same.

Perhaps I invited the danger, I mused, to disrupt the flatline of pacification.

And in the end, I’ll die

just to validate my aliveness.

But that’s life, I thought, ever brushing shoulders with destruction, so that we only live to flirt with death, and dance that lifelong courtship dance;

and O! how it hurts, O! how it tickles, O! how it crashes, O! how it ripples —

—>>>> Life and Death, /\ Death and Life, <<<<—

the silence of a blade across flesh, the scream that accompanies the orgasm explosion,

the hushed quiet of a broken-record life on repeat and the rushed adrenaline exhilaration when mundane Reality is finally pierced: LIFE

from one moment to the next, and yet all at once,

tranquil and torrential,

sublime and mundane,

pleasure inseparable from pain.

And it’s all terrible, and it’s all beautiful.

I could feel it all at once—the indefinable IT—

the despair and the rapture,

the fear and the pleasure,

desperation and reverence,

wholeness and severance,

mortal and eternal,

without and within.

It felt perfect.

A version of this story was originally published at Radically Enlightened.

Note from the HE Team: We’re unsure of the truth of some of the claims in this story: for instance, the suggestion that spirit guides and power animals exist. Nonetheless, we found this piece to be significantly valuable and worth publishing.

Jack E Othon

Jack E is the creator of Radically Enlightened, a blog dedicated to expanding global consciousness. Insta - https://www.instagram.com/jeothon/