@EdGibney • • 10 min read

Yes, We Actually Can Judge Right from Wrong

Morality binds people into groups. It gives us tribalism, it gives us genocide, war, and politics. But it also gives us heroism, altruism, and sainthood.

— Jonathan Haidt

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but there is definitely something wrong with your morality.

No experts have agreed that one system of ethics is right so far so, unless you know something the rest of us don’t, yours must be wrong somewhere.

“But I know right from wrong!” you protest.

Well, you may avoid murdering anyone on the way to work, or cheating on your wife, or lying to everyone about your credentials. You might help the old lady across the street, tell your family you love them, and work hard at whatever it is you do. You might be a generally good person who does generally good things. But general morality is easy.

So easy in fact, that we stop thinking about the field and let the few sticking points at the edges just remain stuck. We give up when the real difficulties arise, because we’re so comfortable believing that we are good an overwhelming majority of the time. But this aversion to the grey zone between right and wrong — the blurry ethical lines running through abortion, stem cell research, and the legalisation of drugs — prevents us from changing the world for the better.

The paradox is this: even if you consider yourself a good person, unless you dig a little deeper you might be doing the world a disservice. By settling for moralities as “just being different” you are playing a small part in some of the biggest problems in the world — religious wars, political rifts, the destruction of the environment, and unsustainable levels of inequality. None of these problems have a rule book or set of commandments every one can agree on, so the difficulties just fester. And no one can fix them.

My aim with this article is to change that. I recently published an academic paper that proposes the only objective solution to these problems.

A New Basis for Moral PhilosophyAnimal behaviorists have discovered that many different social animals are driven by moral emotions to perform actions for the benefit of others. Monkeys, elephants, and wolves all obey norms of behavior and occasionally sacrifice for the good of the group. But none of these animals are very farsighted; their morality is limited. Somewhere during our evolutionary history, we humans placed religion on top of these deep-seated feelings, which we used to both teach morals and enforce them when others in our group are not around.

Religion helped human ethics expand beyond our own lifetimes and to all of humanity. It helped many groups survive and thrive. But all religions were founded on one imaginary being or another so they were never justified to the point where one could reliably persuade followers of other religions. This has caused a lot of problems, to say the least.

When I was about 25, I too became unconvinced by the arguments of my religious upbringing and I decided once and for all that I was an atheist. I no longer believed in the Judeo-Christian god that defined theism. But I remember talking to a friend at the time who had been raised as an atheist and I said that I didn’t know how I would ever teach kids right from wrong without all the catechism and religious rules that had been used to get me to my own moral adulthood. She said you didn’t need all that—you just needed to tell kids what society had decided was right and wrong.

When I asked how society decided those things, she didn’t have an answer. It turns out no one did. I began really searching for a secular, natural basis for morality, but I only had a few college philosophy classes in my background so I didn’t know that this was perhaps the biggest problem in the history of moral philosophy. Almost 20 years later—now that my article offering a solution to this problem was published in the peer-reviewed ASEBL Journal1—I know better.

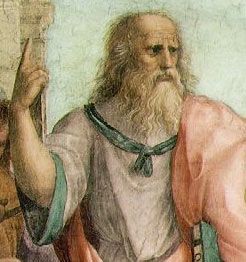

The Euthyphro Dilemma

Plato was the first major thinker to raise a difficult question for religious moralists when he posed what is known as the Euthyphro Dilemma about 2400 years ago. In it, Plato asked a religious expert:

“Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?”

In other words, do we just take a god’s word for it that something is good, or would it be good even if the gods didn’t say so? Is there an objective measuring stick for what is good?

Until now, no one has ever found one.

That conundrum didn’t stop religions and other belief systems from telling us how we ought to act though. There is no shortage of sayings about “thou shalt” or “you should” or “do unto others.”

In 1739, however, the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume definitively stated why these moral orders have never been justified. Hume pointed out that all religions go directly from objective descriptions of the world (‘is’ statements), right on to subjective prescriptions of morality (‘ought’ statements), but you cannot get from one to the other using logic alone. This argument from Hume came to be known as the is-ought divide and for over 275 years it has never been crossed.

Hume didn’t think this divide was an uncrossable chasm though. He knew we get from is to ought all the time in our daily lives, but only ever by using “wants.” For example: there is a cookie in the jar. I want a cookie. I ought to go open the jar. Note, however, that you can’t use the first and third of those statements without the second one in between. Otherwise, you might say you didn’t want a cookie so there’s no reason you ought to go get one. Morality works the same way. If a church says, “Max is a liar. Max ought to be punished.” they have committed a logical error. Where is the want? And if your moral rules are to be universal and objective, then this want has to be universal and objective too. What kind of want could that be?

For hundreds of years, no one knew. When the Enlightenment showed us we should value the scientific method over revelation as the standard for proof, intellectuals began logically proving that religion was wrong, but they never managed to prove what is right.

Some of us began to throw off religion, but then we were left with a massive void. All of our morals had been justified by revelation, but to be modern meant we could no longer rely on all that wisdom. The moral relativism that a few thinkers realized was all we had gradually began to spread throughout the populace. Once religions were separated from the state and baby boomers threw off the shackles of tradition in institutions across all of society, this relativism took hold in academia. Now, virtually everyone gets taught these ideas. If you are reading this, you probably aren’t a religious dogmatist so you’re one of these relativists at some level in your morality. The article, Moral Relativism and the Crisis of Contemporary Education, showed one reason why:

“It starts at the top, in the journal articles and published books that secure tenure and impose the ideological dictates determining the construction of curricula, the pedagogy taught in graduate programs, and the way we train teachers from kindergarten through high school and beyond. At the highest levels of academia, the tenured professoriate — and the professors, deans, provosts, chancellors, and university presidents who almost always arise from the privileged ranks of this tenured class — there exists a dangerously monolithic echo chamber, where relativistic, post-modern ideas about the world, culture, and truth have become calcified.”

In another recent article, Why Our Children Don’t Think There Are Moral Facts, we see the consequences of this in a quiz the author pulled together from various online instructions related to the Core Curriculum:

“Here’s a little test devised from questions available on fact vs. opinion worksheets online: are the following facts or opinions?

- Copying homework assignments is wrong.

- Cursing in school is inappropriate behavior.

- All men are created equal.

- It is worth sacrificing some personal liberties to protect our country from terrorism.

- It is wrong for people under the age of 21 to drink alcohol.

- Vegetarians are healthier than people who eat meat.

- Drug dealers belong in prison.

“The answer? In each case, the worksheets categorize these claims as opinions. The explanation on offer is that each of these claims is a value claim and value claims are not facts. This is repeated ad nauseum: any claim with good, right, wrong, etc. is not a fact.”

This kind of relativism, once cocooned among a few ineffectual intellectuals, has become widespread and entrenched, with nothing but religion to combat it. (The author of the first article recommended home schooling based on “traditional values” as his solution to this problem.)

Except for maybe a few obviously heinous caveats, every type of morality is just an opinion so everyone in this relativistic world gets to do “whatever they want.” But if you remember the discussion on Hume, “wants” are precisely what we are combing through to find a bridge between the “is” statements of the objective world, and the “ought” statements of moral prescriptions. If we all want different things, there can’t be an objective morality. But is there one thing we all want? I say there is.

The Universal “Want”

To get there, look at the evolutionary history of moral philosophy and see how morals have grown as our wants for different areas of concern have grown. First, animals developed norms of behavior that helped individuals stay alive. Emotions like fear, rage, seeking, and lust told them what they wanted and guided their behaviors. Today, we don’t consider these wants moral because they are only selfish concerns, but eventually we also developed cooperative emotions that helped us care for others, sometimes at the short-term expense of our selfish desires.

In 1981, moral philosopher Peter Singer wrote The Expanding Circle, which explained how a rational regard for the self could logically lead to taking the views of others into account, which Singer was able to expand until “others” encompassed all of humanity. In later works, Singer pushed this consideration to all sensitive species. But is this even enough? Is it a universal want to want to consider the needs of sensitive creatures alive today? Can we all agree with that?

Not quite. In 1998, biologist E.O. Wilson published the book Consilience, which sought a grand unification for the study of the biological sciences. Biology is literally “the study of life” and Wilson believed an understanding of scale was the means by which the separate biological sciences could come together to form a universal picture of all of life. According to the magnitude of time and space used for analysis, the basic divisions of biology from the bottom to the top were:

(1) Biochemistry -> (2) Molecular Biology -> (3) Cellular Biology -> (4) Organismic Biology -> (5) Sociobiology -> (6) Ecology -> (7) Evolutionary Biology.

The sum of these seven divisions provides a comprehensive picture of life. From the short-term atomic scale of biochemistry, all the way up to the complex systems of ecologies interacting and changing over evolutionary timeframes—everything we could ever want to care about falls somewhere in this spectrum.

Working backwards, we also see that the most basic concern we can have for life is that it survives. Everything else is secondary to that. Without survival, there is nothing to have any other wants. If a want leads to extinction, it must be abandoned, or the want itself won’t survive either. This is how we finally arrive at the universal want that bridges the famous is-ought divide: we all want life to survive over the long term of evolutionary timescales. All of us, all forms of life, in any period of time, if able to be asked and give a reply, would say yes, we want that. That’s an objective basis for morality we can all agree to.

Life IS. Life WANTS to remain an is. Life OUGHT to act to remain so.

Problem solved, right?

Well, this universal want is not an easy one to navigate. Moral conflicts arise when there are conflicting needs between the various spheres of life. Some actions may be good for me, but not for her. Good for us, but not for them. Good for humans, but bad for the pandas. Good for the hungry people now, but possibly bad for the evolution of plants over the long-term. Etc., etc.

We won’t always know how to weigh the importance of these needs. We’ll make mistakes when we try. And there are myriad ways to benefit life. From the biological sciences, we know we need:

- Suitability to an environment.

- Adaptability to changes in the environment.

- Diversity to handle fluctuations.

- Cooperation to optimise resources and reduce the harm that comes from conflict.

- Competition to spur effort and progress.

- Limits to competition to give losers a chance to cooperate on the next iteration.

- Progress in learning, to understand and predict actions in the universe.

- Progress in technology, to give options for directing outcomes where we want them to go.

We objectively know we need these and other abilities to survive.

Even though we may disagree with others about the best means to an end, we finally have an end we can all agree with. It doesn’t require religion to want the survival of life over the long term, and the objectivity of this goal gives us criteria by which we can judge relativistic ideals as actually right or wrong.

This universal desire gives us a connection to each other and to all the forms of life we will ever find. The difficulty and never-ending task of reaching this goal means we should have compassion and understanding for others as we humbly work to achieve it. That kind of connection and compassion is exactly what we need to cross the divides that cause our biggest problems, so we really ought to consider changing the basis of our morality to this want that I’ve described. It seems to finally be the right one.

Footnote- To read my paper Bridging the Is-Ought Divide in full, see the original journal from the Association for the Study of Ethical Behavior and Evolutionary Biology in Literature at: http://www.sfc.edu/uploaded/documents/publications/ASEBLv11n1Jan15.pdf

![Seneca’s Groundless Fears: 11 Stoic Principles for Overcoming Panic [Video]](/content/images/size/w600/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/seneca.png)