Matt Karamazov • • 16 min read

The Simulation Argument: Why We Might Already Be Living in Virtual Reality

The essay that you (or your avatar) are reading right now is about the Simulation Argument, formulated by Professor Nick Bostrom of Oxford University. But really, it’s a story about uncertainty.

It’s a cautionary tale against intellectual hubris and snobbery, as well as an admonition to enrich your own life and expand your range of possibilities.

Take the plunge with me, and we’ll see why Professor Bostrom thinks it’s possible we’re living in a computer simulation, run by advanced humans in some distant future.

THE SIMULATION ARGUMENT

In a famous paper entitled, Are We Living in a Computer Simulation?, Bostrom argues that at least ONE of the following propositions must be true:

(1) The human species is very likely to go extinct before reaching a “posthuman” stage.

(2) Any posthuman civilization is extremely unlikely to run a significant number of simulations of their evolutionary history (or variations thereof).

(3) We are almost certainly living in a computer simulation.

Think about it: If crazy high-tech future humans simulate billions of universes, there will be billions of fake universes and just one “base reality.” The chances of being born into the base reality (as opposed to one of the simulations) would be astronomically low. Thus, if such a thing has already happened, we’re probably in a simulation right now.

However, we may not be. If our species is sufficiently volatile and self-destructive, such that we’re unlikely to survive long enough to become posthuman, or if for some reason our posthuman descendants don’t care much for simulating universes, we’re probably not living in a computer simulation.

And that’s the Simulation Argument. It’s really pretty straightforward and easy enough to understand. But as you can see, it’s the sort of idea that could keep you awake at night, wondering how “real” our reality really is.

For his part, Bostrom doesn’t claim to actually believe that we’re living in a computer simulation; he just admits that it’s possible.

In fact, Bostrom states:

“We may hope that (3) is true since that would decrease the probability of (1), although if computational constraints make it likely that simulators would terminate a simulation before it reaches a posthuman level, then our best hope would be that (2) is true.”

In other words, hopefully we are in a simulation, Bostrom says, because that would mean we aren’t likely to destroy ourselves entirely. However, if we are in a simulation and the simulators might “turn off” our reality sometime soon because keeping it running requires too much computing power, we should hope that our descendants simply don’t tend to simulate their past for whatever reason.

Personally, if one of those three propositions must be true, I hope it’s (2) regardless. I’m not sure why we would hope first and foremost that we are living in a simulation, rather than hoping that our descendants don’t care much for running ancestor simulations.

I highly recommend reading the original Simulation Argument, and I think you’ll find that it’s not nearly as intellectually intimidating as it might first appear. Indeed, compared to Nick Bostrom, my skull is a bag of hammers, and I didn’t have TOO much difficulty understanding it (although I did have to read it twice before I felt like I finally “got” it).

Now, while attempting to avoid references to The Matrix, let’s dig deeper into the Simulation Argument and its relation to the world of dreams, in hopes of further illuminating its mind-bending implications.

SIMULATIONS, DREAMS, IGNORANCE

“We accept the reality of the world with which we’re presented. It’s as simple as that.”

— Christof, The Truman Show

Doesn’t it strike you that existence is really quite weird?

I said that I wouldn’t make too many Matrix references, but I didn’t say anything about Men in Black references, so here goes:

Think back to what we used to KNOW about life on earth:

We used to know for a fact that the earth was the center of the universe.

We used to know that leeches were the cure for freakin’ everything.

We used to know that our hands were always clean and that washing them before performing potentially life-saving surgeries was a waste of time.

In light of all this, reflect for a moment on the likelihood that what we “KNOW” today represents some kind of absolute truth.

There seems to be an unbreachable chasm between the subjective and objective world. So says Chuck Klosterman in one of the most thought-provoking books I read in 2017, But What If We’re Wrong?.

Speaking of weirdness, Klosterman says:

“Every night, we’re all having multiple metaphysical experiences, wholly constructed by our subconscious. Almost one-third of our lives happens inside surreal mental projections we create without trying. A handful of highly specific dreams, such as slowly losing one’s teeth, are experienced unilaterally by unrelated people in unconnected cultures. But these events are so personal and inscrutable that we’ve stopped trying to figure out what they mean.”

Every night, most of us enter a dream-state where the physical laws of the universe are completely suspended, and we have little to no idea what this means.

Many people don’t think dreams are worth looking into. But I think that in dreams, such as in life, it all matters, or none of it matters.

Would a simulation be much different from a dream, experientially?

There is nothing to suggest that a technologically advanced civilization with enough computing power couldn’t recreate everything that we think is real.

The precise values of gravity and the mass of electrons could have been set by a simulator which created the experience we’re all having right now.

Nobody is really sure about the existence of any possible “upper bound” on the amount of computing power that may be available in the future. And as Professor Bostrom explains, a hypothetical simulator would only need a sufficient amount of computing power to ensure that the simulated humans (us) don’t notice any “irregularities.” You know, cars starting themselves, or cats barking—that kind of stuff.

He goes on to say:

“The microscopic structure of the inside of the Earth can be safely omitted [from the simulation]. Distant astronomical objects can have highly compressed representations: verisimilitude need extend to the narrow band of properties that we can observe from our planet or solar system spacecraft. On the surface of Earth, macroscopic objects in inhabited areas may need to be continuously simulated, but microscopic phenomena could likely be filled in ad hoc. What you see through an electron microscope needs to look unsuspicious, but you usually have no way of confirming its coherence with unobserved parts of the microscopic world…Should any error occur, the director could easily edit the states of any brains that have become aware of an anomaly before it spoils the simulation. Alternatively, the director could skip back a few seconds and rerun the simulation in a way that avoids the problem.”

Who might this “director” be?

Could it be “us” in the future, curious enough about our evolutionary past to want to run a simulation in order to view history over again, or perhaps to play around with the variables?

Chuck Klosterman chimes in with a humbling proposition:

And in that case, there IS a simulator – maybe some kid in his garage in the year 4956 – who is determining and defining the values of the constants in this new universe that he built on a Sunday morning on a supercomputer. And within that universe, there are beings who will wonder, “Who set the values of these numbers that allow stars to exist?” And the answer is the kid. There WAS an intelligent being outside that universe who was responsible for setting the values for these essential numbers.”

Turning the microphone back to Professor Bostrom, he says:

“If we are living in a simulation, then the cosmos that we are observing is just a tiny piece of the totality of physical existence. The physics in the universe where the computer is situated that is running the simulation may or may not resemble the physics of the world that we observe. While the world we see is in some sense “real”, it is not located at the fundamental level of reality.”

And just like a dream… we would NEVER be able to know for sure.

Except, perhaps, when it ends.

“Once upon a time, I dreamt I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, to all intents and purposes a butterfly. I was conscious only of my happiness as a butterfly, unaware that I was myself. Soon I awaked, and there I was, veritably myself again. Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man.”

— Zhuangzi

Bostrom then considers an “objection” that I had been carrying around while reading the first part of his Simulation Argument paper: Why does it have to be an ancestor simulation?

Couldn’t it be some sort of training program or virtual reality experience solely for entertainment?

He cuts me off by saying that:

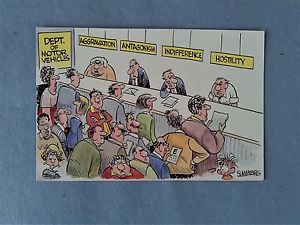

“In addition to ancestor-simulations, one may also consider the possibility of more selective simulations that include only a small group of humans or a single individual. The rest of humanity would then be zombies or “shadow-people” – humans simulated only at a level sufficient for the fully simulated people not to notice anything suspicious.”

(I KNEW those people at the Department of Motor Vehicles were just “shadow-people”!!!)

All right, time to hold onto something to keep the room from spinning. Let all that sink in, and keep forging ahead.

CRITICS AND SUPPORTERS OF THE SIMULATION ARGUMENT

There are people out there who *GASP* don’t think that the Simulation Argument is worth considering at all.

These are likely the same people who keep turning my music down at the gym, or tell me that being a writer isn’t “practical”.

But they also include physicist Lisa Randall, author of Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs, and several other hyper-intellectuals.

Commenting on claims made by some that a recent glitch at the Oscars meant that there were visible “cracks” in the simulation, she said:

“At this point, we cannot prove that we do or don’t live in a simulation. More to the point, there is no reason to believe that we do. However, we can pretty much be sure that people will do amazing things and they will also mess up in spectacular ways.”

In contrast, a hero of mine, Elon Musk, claimed publicly that “the odds that we’re in base reality is one in billions.”

Another really smart dude, David Chalmers, professor of philosophy at New York University, said that we’re not going to get proof that we’re not in a simulation, because any evidence that we get could be simulated. He’s also said:

“If it turns out we really are living in a version of “The Matrix” [his reference, not mine], though — so what? Maybe we’re in a simulation, maybe we’re not, but if we are, hey, it’s not so bad.”

Some have said that it’s also a lot of hubris to think that WE would be what ended up being simulated, but Max Tegmark (a professor at MIT) has some words of wisdom for us in this case:

“My advice is to go out and do really interesting things, so the simulators don’t shut you down.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s follow the evidence!

Find even more heart-stopping books and food for thought over at the Stairway to Wisdom, a new offering from HighExistence. It comes with a premium weekly newsletter featuring deep dives into the best of books and literature, new book breakdowns each and every week, and much, MUCH more!

THE EVIDENCE OF SIMULATION

As David Chalmers observed, we’re never going to get “evidence” that we’re living in a simulation, because any evidence that we could possibly obtain might just have been simulated.

But we can look for clues. Glitches in the program, if you will.

Also, we can try and figure out if the structure of our perceived reality could even allow for such a state of affairs to exist.

The first step in all of this, of course, is to suspend your certainty about what’s really going on here.

I have no first-hand, empirical claim to absolute truth, and neither do you.

So where can we look for evidence that we may be living in a computer simulation?

Well, my first choice when it comes to evidence of living in a simulation would be the mathematical nature of our universe itself. It’s broken up into pieces (subatomic particles) like pixels in a video game. The laws of physics are computable and they have definite parameters. That means that they can be simulated.

The Simulation Argument also accounts for a lot of strange stuff related to quantum mechanics, such as the measurement problem, which deals with the fact that things only become defined when they are being observed.

Maybe you DO need a conscious observer, like a conscious player of a video game, in order to resolve this measurement problem. This strikes me as the second-greatest “evidence” that we may be living in a computer simulation.

The possibility still exists, too, for near-incontrovertible evidence to emerge that we are living in a simulated world. That is, if we were to go on to create our OWN simulations, we could be fairly certain that we were not in the base reality.

Nick Bostrom states in his paper that:

“If we do go on to create our own ancestor-simulations, this would be strong evidence against (1) and (2), and we would therefore have to conclude that we live in a simulation. Moreover, we would have to suspect that the posthumans running our simulation are themselves simulated beings; and their creators, in turn, may also be simulated beings. Creating simulations would be evidence that we might live in one.”

Beyond all this, there may be one final piece of evidence which could tell us conclusively whether or not we are living in a computer simulation: The moment of our own eventual death.

The moment of death may be the moment of truth. Do we see ones and zeroes? The face of a loving and expectant god? Impenetrable darkness?

Or do we apprehend nothing at all, questions left unanswered, because we have ceased to exist and to be conscious of anything? Maybe Epicurus accurately described the nature of death in this classic statement:

“Why should I fear death?

If I am, then death is not.

If Death is, then I am not.

Why should I fear that which can only exist when I do not?”

Perhaps death will be the moment when the veil is pulled back and all is revealed, or perhaps it will be nothing at all.

CAN WE SIMULATE GOD?

One of the things I find fascinating to contemplate is the relationship between the Simulation Argument and ideas of God.

As a radical skeptic in the same tradition as Diogenes and Montaigne, I hold no personal illusions about a kind and loving God who is waiting for my return to His kingdom.

But I have to admit that I like that idea. Part of me wants it to be true.

And it could be true, even if we’re living in a simulation. The base reality would have to have emerged inexplicably from nothingness at some point, leaving open the possibility that it was created by some kind of omnipotent being.

Furthermore, it’s interesting to consider the similarities between a hypothetical “director” of a simulated universe and a deity.

In fact, most all of the classical questions we ask about a hypothetical God can be asked about a hypothetical simulation-director:

“Why did the director of our world decide to include evil and suffering? (Can they change these settings in the preferences?)”

“What does the director want from us? Is there a specific way that he or she wants us to be living our simulated lives? Or is it purely for his or her own entertainment?”

“Where did the original, non-simulated world come from?”

Could we, somehow, maybe by virtue of our acts here on earth “graduate” to a higher level of the simulation? Someplace “better”?

Or, conversely, could we be punished for our cruelty and waste here on this level of the simulation and be sent to a much worse place for our next “generation”?

How should we live in order to prevent that from happening?

In our universe, we create simulated worlds all the time. Neil deGrasse Tyson has said, “We don’t think of ourselves as deities when we program Mario, even though we have the power over how high Mario jumps.” There’s no reason for Mario to believe that we’re perfectly omnipotent, even though we control everything that he does.

Basically, anyone who created the simulation we may or may not be living in would be akin to a god, at least to us. Maybe it’s some kid in the next universe up, as Chuck Klosterman postulated, but it really could be anyone.

How should we live in light of these considerations, especially given that we can never KNOW if we are living in a computer simulation? It’s to this question that we now turn.

HOW SHOULD WE LIVE IN A SIMULATION?

Ah, now we get to the good stuff. If we really are digital beings living inside a simulation, or if there’s even a remote possibility of that being true, how should we live?

I’ll give the first word to Chuck Klosterman:

“In fact, I’d say the first principle to adopt in this scenario would be the same as the one we use in regular life – don’t get terminated. Stay alive. But beyond that?”

Point well taken.

What Bostrom says, and what looks like the right idea at first glance, is that because we have no reason to believe that either of these possibilities is more likely than the other, the Simulation Argument provides no real reason to change the way we live our lives.

But I disagree, and here’s why…

First, the technical objection from Robin Hanson, a research associate at the Future of Humanity Institute:

“In general, your decisions should be based on a weighted average over the different possible worlds you might live in. If you assign a non-zero subjective probability to the possibility that your descendants will create sophisticated simulations which include people (real or simulated) like us, ignorant of their status, then you should assign a non-zero subjective probability to the possibility that you now live in such a simulation. So to the extent that there are consequences of your actions which are different in a simulated world, and you care about these consequences, a non-zero probability of simulation should influence your decisions.”

To put it more simply, Hanson is saying that if you think there is any chance we are living in a simulation, and if you would behave differently in a simulated world for whatever reason, you should probably behave somewhat differently than you otherwise would, given your belief that we may be living in a simulation.

Here are what I would consider the “rules” for living in a simulation:

1) Don’t get terminated. Unless you’re aiming to experience the evidence firsthand regarding whether or not you live in a simulated universe (though, again, death could easily be inconclusive, as we may just cease to be aware of anything). I, for one, want to see where this hypothetical simulation leads.

2) Spend the rest of your life testing the limits, and, in effect, trying to figure out what you “can’t” do. For this to work, assume there is no “can’t”. What is your body capable of? Can you make one person’s life demonstrably better? Can you save an endangered species? Can you become CEO? Can you become world champion? Can you get her to like you? What are the thoughts you can’t have? Are there aspects of this simulation that its creator never considered? What’s beyond the stars?

3) Look for ways to “break” the simulation. A simulated world is a theoretically “solvable” world, and maybe you can crack the code. Maybe, to save computing power, the stars only light up when you’re looking at them. Or buildings turn into ones and zeros once you leave a particular city.

4) Assuming you don’t want the simulation to be turned off, you should do everything in your power to keep the director interested in maintaining the simulation. Go out and do wild things; make a name for yourself; create something epic; become larger than life. Be part of history, or better yet, MAKE history. Cause dramatic shit to happen. At least, that’s what you would do if you assumed the director had a human-like interest in the entertainment or intrigue value of their simulations.

5) Find out what kind of behavior is rewarded in this simulation, and then live your life that way. If you find Erich Fromm’s idea appealing that love is the only rational answer to the problem of human existence, then maybe you should find a way to bring more of that into the world.

In the end, learning that you’re not real doesn’t feel any different from the way you felt before. Even if you’re not “alive”, life goes on, says Klosterman.

Let’s tie this all together and bring it back to “base reality”…

CONCLUSION

“Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

— Dylan Thomas

An overarching theme of this essay is that when you get right down to it, we humans can’t be sure about even the most fundamental “facts” of existence that we take for granted.

Yet, when you survey the history of human thought (and especially listen to how people talk today), you are struck by the fact that everybody seems so SURE of themselves.

The fact is that it’s impossible to have satisfactory knowledge of anything without knowing all things — and that’s just not going to happen.

I’ve laid out the case for why we might be living in a simulation, and I’ve given some possible avenues of exploration with respect to how we might lead our lives in the face of this possibility.

But we each need to step out in front of the unknown for ourselves. There may be a darkness coming for you that you can’t escape, but there may also be a benevolent “director” waiting to welcome you home.

Nobody knows.

Existential courage then becomes the highest virtue.

We then have a reason to hear each other out, and to doubt our own certainties. We also have innumerable reasons to stop hiding, and to aim to live our best lives. Not fearing disaster, nor taking refuge in sentimentality, but rather engaging meaningfully with the world, for as long as this privilege is to be ours.

The Simulation Argument, then, serves as an empowering thought experiment and a call for radical humility, healthy skepticism, and above all, infectious joy.

Because if ours is a simulated universe, there is a good chance that it will someday end. How will this knowledge change your life?

All the best,

Matt Karamazov

Are You Driven to Pursue Your Curiosity?

Find even more heart-stopping books and food for thought over at the Stairway to Wisdom, a new offering from HighExistence. It comes with a premium weekly newsletter featuring deep dives into the best of books and literature, new book breakdowns each and every week, and much, MUCH more!

![Seneca’s Groundless Fears: 11 Stoic Principles for Overcoming Panic [Video]](/content/images/size/w600/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/seneca.png)