Jordan Bates • • 17 min read

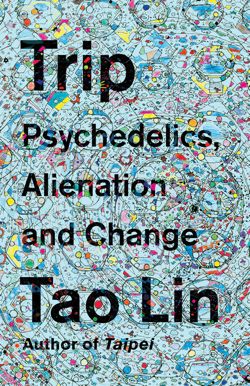

Beyond Existentialism: An Interview With Tao Lin

“From what I understand of existentialism, it says we should make our own meaning in an indifferent universe. [Terence] McKenna corrected Sartre by saying nature is not mute, as Sartre felt, but obviously it is humans who are deaf. Existentialism seems like an ends, but I’ve learned that it can be more like a phase.”

— Tao Lin

When I found out Tao Lin was writing a new book about psychedelics and Terence McKenna, I knew I needed to read it.

I’d been a fan of Tao’s writing for years, having deeply enjoyed his novels Eeeee Eee Eeee and Tai Pei. Tao’s writing style is non-ordinary, uncanny, highly original, and he has a knack for translating the absurd and alienating aspects of modern life into vivid prose.

So I read Trip: Psychedelics, Alienation, and Change as soon as I could get my paws on a copy, and I was not disappointed. It’s undoubtedly one of the best books I’ve ever read.

A genre-bending tale, Trip is simultaneously a biography of Terence McKenna, a zany psychedelic memoir, and a well-researched introduction to psychedelics and a number of other topics, such as mankind’s Paleolithic Goddess-worship and the remarkable findings on human nutrition by Weston A. Price.

At the beginning of Trip, we find Tao feeling “zombielike and depressed” on September 14, 2012, after recently completing his novel, Tai Pei. Tao notes that he had been “embodying a ‘whatever it takes’ attitude regarding amphetamines and other drugs and completing my novel” in the weeks prior.

Unbeknownst to Tao, he was about to discover—via an offhand comment from Joe Rogan, whom Tao was “vaguely aware of as the host of Fear Factor”—Terence McKenna, a man who would change his life.

In the following week or so, Tao listened to ~30+ hours of McKenna audio and found himself surprised by his own “unprecedented level of interest.” He writes:

“McKenna seemed excited and delighted by topics I’d just finished expressing in my novel as sources of bleakness and despair and confusion—technology, drugs, human existence, the future.”

This initial deep dive down the McKenna rabbit hole was the beginning of a kind of rebirth process. It sparked a psychedelic and intellectual journey that would lead Tao to recover from a dark period of addiction and discover the wondrous enchantments of nature in a way he previously never had.

Trip is the stranger-than-fiction record of this journey. Tao’s inimitable writing style renders the book unlike any other on psychedelics, and his keen powers of articulation result in some of the most lucid and striking descriptions of the psychedelic experience ever recorded.

I recently had an auspicious opportunity to converse with Tao via email and ask some questions about Trip. I enjoyed collaboratively spelunking his mind on the subjects of living psychedelically, leaving society, transcending existentialism, DMT entities, re-enchanting nature, and more.

I hope that you, dear reader, will appreciate this interview as much as I did, and find many gems of insight herein. Without further ado, here’s my conversation with Tao Lin:

An Interview With Tao Lin

First of all, congratulations on Trip. I read the book cover to cover with great interest, and it’s a phenomenal achievement. What, for you, was the most fascinating and/or meaningful aspect of the process of creating this book?

Thank you for reading it. The most fascinating aspect was maybe the research, in which I learned startling, world-elucidating information on the CIA, FDA, USDA, EPA, DNA, MKUltra, glyphosate, humankind’s Goddess-worshipping origins, and other topics. The most meaningful aspects were sharing how and what I learned, why it excited or changed me—how, for example, I discovered Riane Eisler through Terence McKenna, leading me to Merlin Stone and other Goddess scholars, causing me to reconceptualize human history as an achievable recovery from the dominator model that emerged ~7000 years ago, instead of as seemingly having always been war-and-male-dominated—and memorializing selected events from my life, like when I disposed my computer on psilocybin on August 5, 2013. By selecting certain events in my life to examine and publish, I’m creating and nurturing narrative threads for my life, increasing and stabilizing my meaning.

In Trip, you share the following quote from Terence McKenna:

“Living psychedelically is trying to live in an atmosphere of continuous unfolding of understanding. So that every day you know more, and see into things with greater depth, than you did before.”

Could you elaborate on your understanding of what it means to “live psychedelically”? What are some practical actions one can take to live psychedelically?

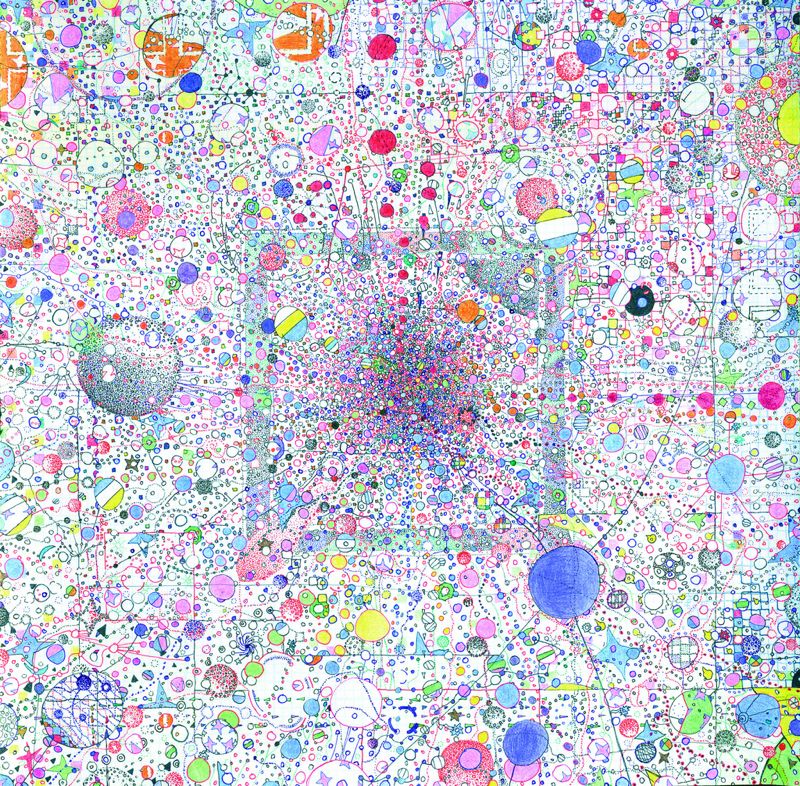

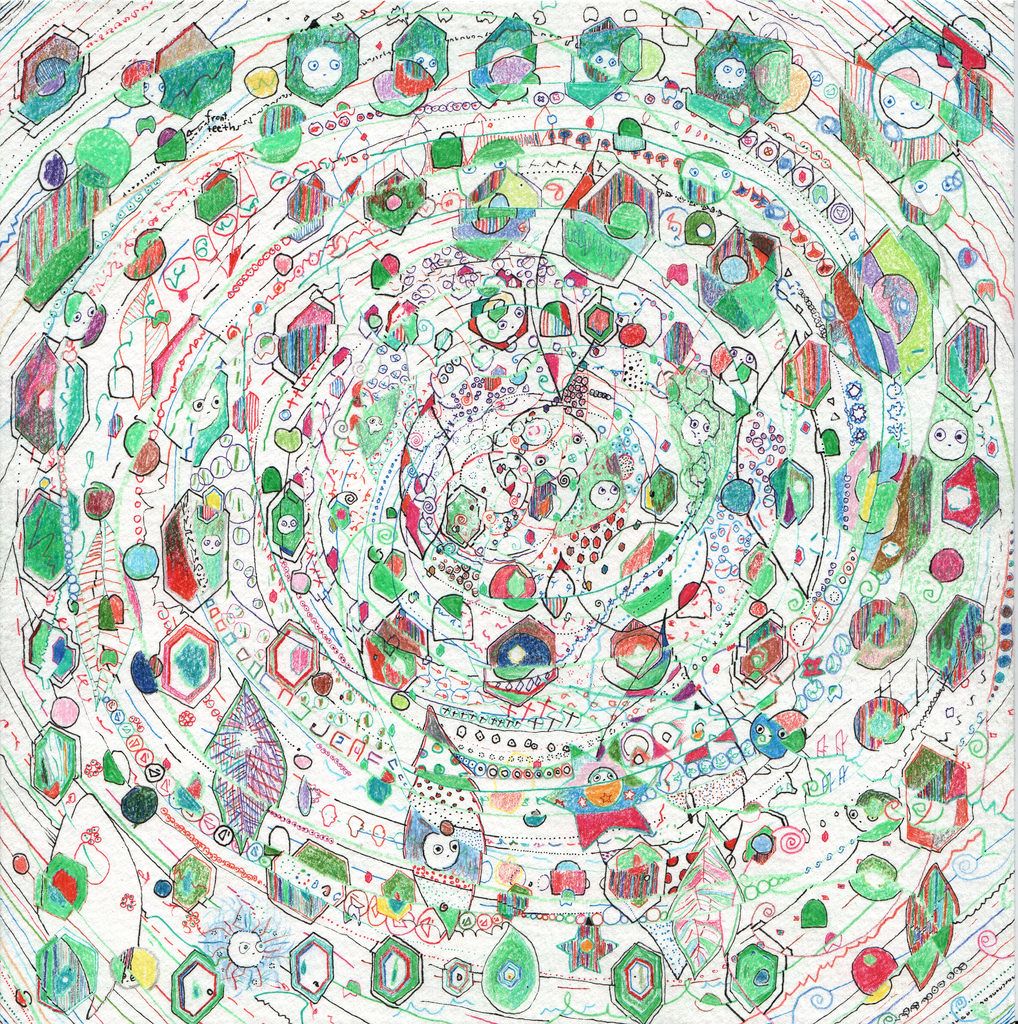

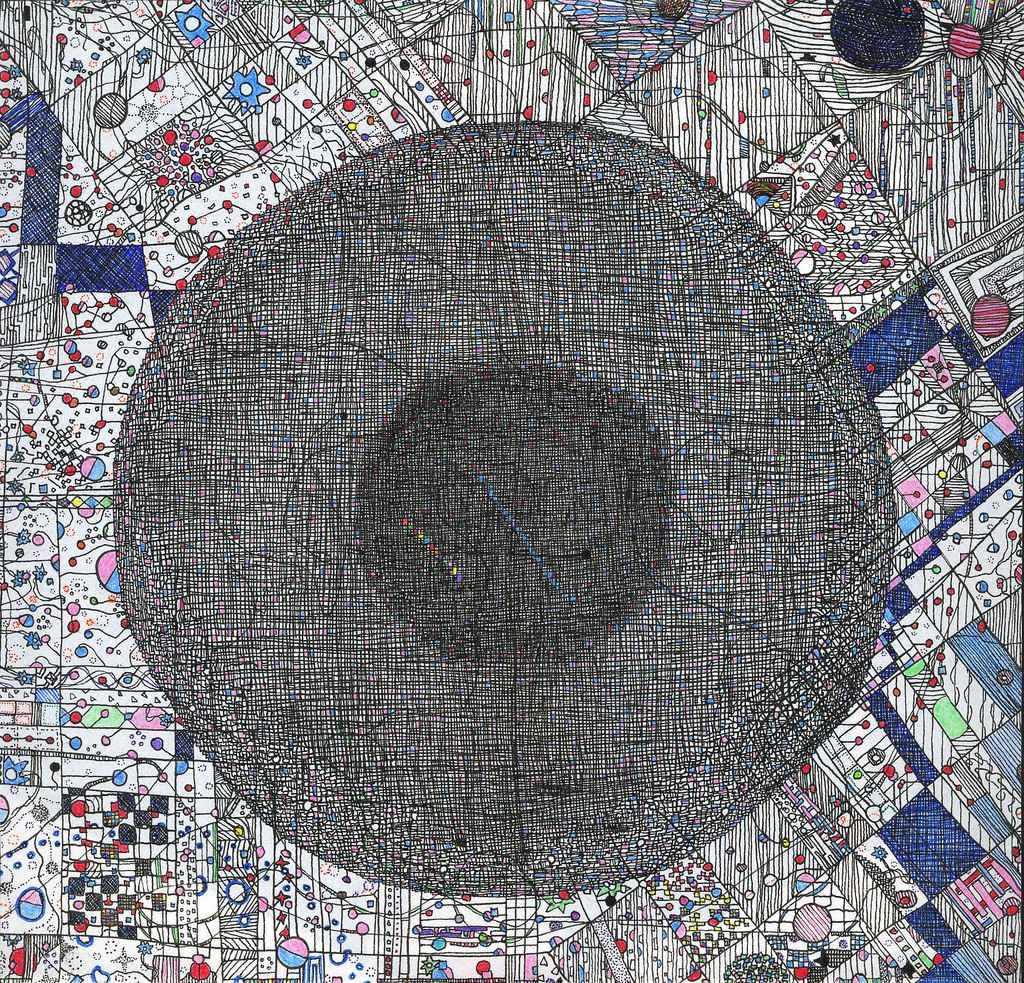

To me, living psychedelically means constant learning, which leads to constant change. I like to think of this in terms of the psychedelic aesthetic—all colors. Instead of McDonald’s or other corporations, which usually choose two or three colors to represent them, a conventionally psychedelic aesthetic needs all the colors, and can still seem psychedelic no matter how many colors you add. It also works with knowledge instead of colors, I think. Adding all sorts of knowledge, and building one’s worldview on that, and never settling into one ideology. I find this inspiring—”trying to live in an atmosphere of continuous unfolding of understanding”—and yet simple. A practical way to do that is to read more books, and read more books that mainstream (and even literary) culture ignores, like Surviving Evil by Karen Wetmore or When God Was a Woman by Merlin Stone; once I started reading nonfiction books that weren’t taught in college, my “continuous unfolding of understanding” happened automatically to some degree, and was exciting.

I understand that Trip was originally titled Beyond Existentialism. Could you say a few words about the meaning of this original title? How might the psychedelic experience help us move beyond existentialism and its assumptions about the nature of reality?

From what I understand of existentialism, it says we should make our own meaning in an indifferent universe. McKenna corrected Sartre by saying nature is not mute, as Sartre felt, but obviously it is humans who are deaf. Existentialism seems like an ends, but I’ve learned that it can be more like a phase. Growing up in Florida, I reacted against Christianity, which said to find meaning in the Bible. It seemed much more reasonable and attractive to me to find my own meaning, so in a way existentialism led me to nature by taking me away from Christianity, which also ignores nature. We’re immersed in meaning, it now seems to me. Nature is pure meaning, it never becomes meaningless, it’s all connected and moving toward greater complexity, but all that can be obscured by governments, corporations, media, school, advertisements, etc., as it was for me my first three decades or so of life.

In Trip, you share a story about a particularly impactful psilocybin mushroom experience. This passage struck me:

“I thought about my life and sobbed, realizing I was finally going to end years of decreasingly enjoyable drug use. I’d ‘realized’ this before but never this confidently, this lucidly. It felt actualized already. I cried thinking about how I was going to distance myself from the writing world and Twitter and Facebook and all culture except books and maybe movies and live alone in a rural area and publish a book about it or never publish another book but just disappear and maybe much later reemerge messianically with a book or just never reemerge. I felt surprisingly able to decide what to do in terms of years and decades instead of hours and days, as if the decisions were literary.”

You go on to say that the main message of this particular psilocybin experience seemed to be to “leave society,” and you’ve written that your next novel will be titled Leave Society. What is it about leaving society that appeals to you? Is there something about leaving society that feels especially urgent or necessary in 2018?

Leaving society appeals to me because of how broad, inclusive, and novel it is, as a directive, for me. I moved to NYC in 2001 for college, and in 2006, when I began publishing books, I got sucked into the now-small-seeming world of newspapers and magazines (where most of literary culture, like reviews, interviews, etc., seems to exist), filling my mind, unconsciously and consciously, with society’s goals and ideas—that there’s good/bad in art, that the New York Times publishes “all the news that’s fit to print,” etc. So I can do almost anything, at this point in my life, decades deep into society, and it can be viewed as “leaving society” to some degree. I think of “leave society” as a synonym for “get less depressed,” “do something new,” and hundreds of other ideas. For me, leaving society—changing what I consume, how I spend my time, what is around me, where I get information—feels urgent and necessary, but in a way that’s exciting and meaningful, so ultimately calming and non-urgent and practice-like.

What would you say to someone who questioned the purpose and value of the psychedelic experience? What is “the point” of ingesting psychedelics, in your estimation?

I would probably ignore them. I don’t like trying to convince individual people of things that I think, because those conversations usually frustrate and depress me. I like carefully building my arguments in prose and in books—deciding exactly what language to use, and what information to give the reader, in what order, with what references, in order to impart information in a persuasive manner. But if someone questioned the purpose of psychededics at a Q&A at a reading, maybe I would try to stress that, from what I can tell, other types of drugs I’ve researched, like statins and proton-pump inhibitors and antidepressants and pesticides, are by comparison absurdly more destructive, so one point of using psychedelics could be to finally try a drug that isn’t sold by a corporation and wasn’t invented in the past hundred years, but has been used by humans for tens to hundreds of millennia.

Sheila Heti described Trip as “a superbly researched, moving, and formally inventive quest for re-enchantment.” Does that description resonate with your own understanding of your project, and if so, what does “re-enchantment” mean to you?

It does, thank you for mentioning her blurb. I view “quest for re-enchantment” as another synonym for “leave society.” I associate enchantment with awe, wonder, magic, having low inflammation, and not being in physical pain—things I rarely or never felt before I began using mushrooms and LSD, and especially before I began using cannabis daily, and also before I encountered Terence McKenna’s ideas and before I focused my attention on nonfiction books and scientific papers instead of the newspapers and magazines. An example of this is something I learned about glyphosate, which is in all of us. Glyphosate inhibits CYP Enzymes, which the body uses, among other functions, to convert endocannabinoids called DHEA and EPEA (which the body makes from DHA and EPA, which are in animal fats) into even more potent endocannabinoids called EEQ-EA and EET-EA. So, just by avoiding glyphosate, and having less of it in us, we can become more stoned—and less inflamed—gradually over time, causing life to seem more enchanting. EEQ-EA and EET-EA were discovered in 2017, the paper announcing it is here.

And, a follow-up to the previous question: Do you think re-enchanting Nature and the Earth is an important project in the modern world? If so, why, and how might psychedelics help in this undertaking?

Psilocybin, DMT, and cannabis—just by being on them—gave me definitions for magic, awe, and enchantment. Magic can be used to describe the rarest experiences. It feels magical when something unexpected and unanticipated happens, and that’s how I felt when I first used psychedelics, and each time I use them. For the first thirty years of my life, everything seemed the same, basically. I was obliviously immersed in culture, where everything was expected and predictable to the point of life seeming often troublingly tedious, and also I was deeply immersed in my own consciousness, which despite its early skepticism against culture via listening to punk music and reading Kurt Vonnegut, had absorbed culture’s views. Coffee, Xanax, and Adderall didn’t take me out of my metaphysical residence and put me elsewhere for a certain amount of time, like psychedelics did and do.

What concise advice would you give your 20-year-old self, if you could send him a message?

My instinct is to not give advice. I’m, on average, happy now, and I’m on a path that excites me, so I feel that everything was necessary to lead me here. I read this quote in The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa when I was around 20; maybe I’d just send it back to myself:

To give someone good advice is to show a complete lack of respect for that person’s God-given ability to make mistakes. Furthermore, other people’s actions should retain the advantage of not being ours. The only possible reason for asking other people’s advice is to know, when we subsequently do exactly the contrary of what they told us to do, that we really are ourselves, acting in complete disaccord with all that is other.

What blogs and/or websites have you found most valuable in recent years?

Weston A. Price Foundation’s website (I recommend their quarterly journal Wise Traditions, which is archived online), Stephanie Seneff’s website and Facebook (for her work on glyphosate, vaccines, autism), GreenMedInfo, Dr. Mercola.

In Trip, you spend a lot of time highlighting the work and story of the ethnobotanist Kathleen Harrison, Terence McKenna’s long-time wife. What was the thought process behind this decision? Do you have any general thoughts about amplifying the voices and influence of women at this moment in history, both in the psychedelic space and the world at large?

This wasn’t planned at first, but it came naturally, as I outlined the book and worked on five drafts with my editor. We decided at some point that we wanted to turn the focus throughout the book from Terence to Kathleen, masculine to feminine. This came naturally in part because there’s a passage in chapter seven on how humans seemed to have worshipped exclusively female deities for at least 28,000 years, from 40,000 to 12,000 years ago, with male deities being a late development, and in part because I’ve learned that women—like nature, psychedelics, and aboriginals—have been egregiously attacked, slandered, oppressed, and ignored over the past 7,000 years. Doing anything to counter that feels meaningful, satisfying, beneficial (to my mind and to humankind’s survival) and exciting to me. Like other suppressed perspectives, feminine perspectives—or, to take it beyond gender, “partnership” perspectives—are, for me, I’ve found, reliable sources of startling, little-known, worldview-complexifying information.

McKenna often pointed out that society has become way too masculine, and that psychedelics and focusing on women, and nurturing partnership qualities in ourselves, can balance that. Because his worldview, gotten from Riane Eisler, and which I now subscribe to, is that both men and women can be to varying degrees both partnership and dominator in their style of being in the world, this isn’t an anti-male stance, it’s subtler and more sustainable than that—it says everyone, at this point, can be more feminine.

A friend suggested to me recently that the term “psychedelic” carries a fair bit of baggage—a few undesirable connotations—given its associations with the excesses of the countercultural movements of the mid-20th century and the anti-psychedelic propaganda that followed. Do you have any thoughts on this? Is it a good idea to begin using “plant medicine,” “entheogen,” “ecodelic,” or other such terms alongside or in lieu of “psychedelic,” as we attempt to propel the global movement to study and utilize these compounds for therapeutic, mind-enlarging, and/or spiritual purposes?

Using those other terms alongside psychedelic seems good to me, but not in lieu, because it seems helpful to remember how the word “psychedelic” has changed, and fun to reclaim the word, reattach all the positives it has had, while disassociating it with its accrued negatives. Plus, the government’s preferred term is “hallucinogenic,” which isn’t accurate; they don’t use “psychedelic.” “Addiction” also seems negative now to most people, but I like to use it literally—I can be addicted to coconuts, blueberries, sunlight, Xanax, cannabis, LSD, anything—because I can still, and more clearly I think, talk about the “addiction” that most people talk about by saying “addiction problem.”

In Trip, you write at length about the deficiencies of our pesticide-ridden global food supply chain, and you frequently share photographs on the Internet of the food you’re eating—often whole, organic produce. Could you share a few of the dietary principles you endeavor to follow, and perhaps share 2-3 books you would recommend to people wanting to optimize their health and well-being via wise dietary choices?

Gradually, over ten years, I’ve eaten increasingly more organic food, and avoided more synthetic compounds. I learned of organic food in college when I Googled how to be less depressed naturally, and learned there were pesticides in food. Buying food grown without synthetic pesticides seems like one of the easiest, most effective ways to help save the world, at this point, or just to reduce suffering, for yourself and others, because the less money spent on food grown with pesticides, the less pesticides will exist, the less farmers will breathe in and live with pesticides, the less pesticides will be in oceans and tap water and plants and animals, the less contaminated future babies will be, etc. Stephanie Seneff has pointed out that people can drastically change the world without needing to influence politicians just by buying organic food. I recommend Nourishing Traditions, Nutrition & Physical Degeneration, and A Mind of Your Own for health.

In Trip, you write the following of an experience you had after smoking DMT in July of 2013:

“Then something happened that scrambled time and erased my memory, interrupting my continuous experience, since birth, of life, even though I remained conscious. I was suddenly so distant from my prior situation inside a body that I could only sense my life—and the world it was embedded in—as a vague myth, shockingly. The blipped passage of my life—a dot of thirty years in a landscape of billions—seemed like a microscopic span of capillary inside the furred ear of an animal on a planet I was rocketing away from in a vessel that had entered a wormhole and departed the universe.

I arrived, with amazement, in a silvery-gray, bulgingly dimensional, complicatedly pulsating, profoundly unfamiliar-feeling, nonphysical place that seemed ancient, public, and, because I couldn’t change perspective, strangely screen-like. It seemed like a dungeon room from The Legend of Zelda (1986) experienced from inside the game; things seemed able to enter from left or right, but nothing did. I felt 50,000 years away from where I was before—not in the past or future but in one of the other directions away from the planet of time. At one point I realized with panic that I needed to experience 50,000 years to return to my prior existence, which I couldn’t remember; I don’t remember how that resolved. Then I was in a sky-like whiteness, densely and glaringly bright. There was something there, and as I tried to comprehend it, it flew away. To chase it, I applied mental pressure behind my eyes. I was trying to use language on it, which I sensed would kill it, which I felt wouldn’t happen because of how swift and elusive it seemed in its own environment, outside language.”

First of all, thank you for this description. It’s one of the most vivid descriptions of a DMT experience I’ve heard or read, and for me it sheds new light on the “timeless” realms to which many subjects report traveling after ingesting certain psychedelics.

What I want to ask about relates to the flying entity you encountered during this experience. Since you noted that you sensed language would kill it, that would seem to indicate that you intuited it as some kind of living being—is that accurate? McKenna famously described communications with “the Logos” during mushroom experiences and encounters with “self-transforming machine elves” via DMT, and countless others have anecdotally reported encounters with various sorts of beings or entities after ingesting DMT, ayahuasca, or other psychedelics. I myself have encountered various sorts of entities during entheogenic experiences. I’m wondering: What ontological status do you grant to these beings and entities encountered during psychedelic experiences? And, if you’re agnostic about this, what do you suspect or intuit with regard to the question of whether these beings and entities are “real”—i.e. have an existence independent of the individual human minds that detect/experience them?

Thank you. I’m glad you liked my description.

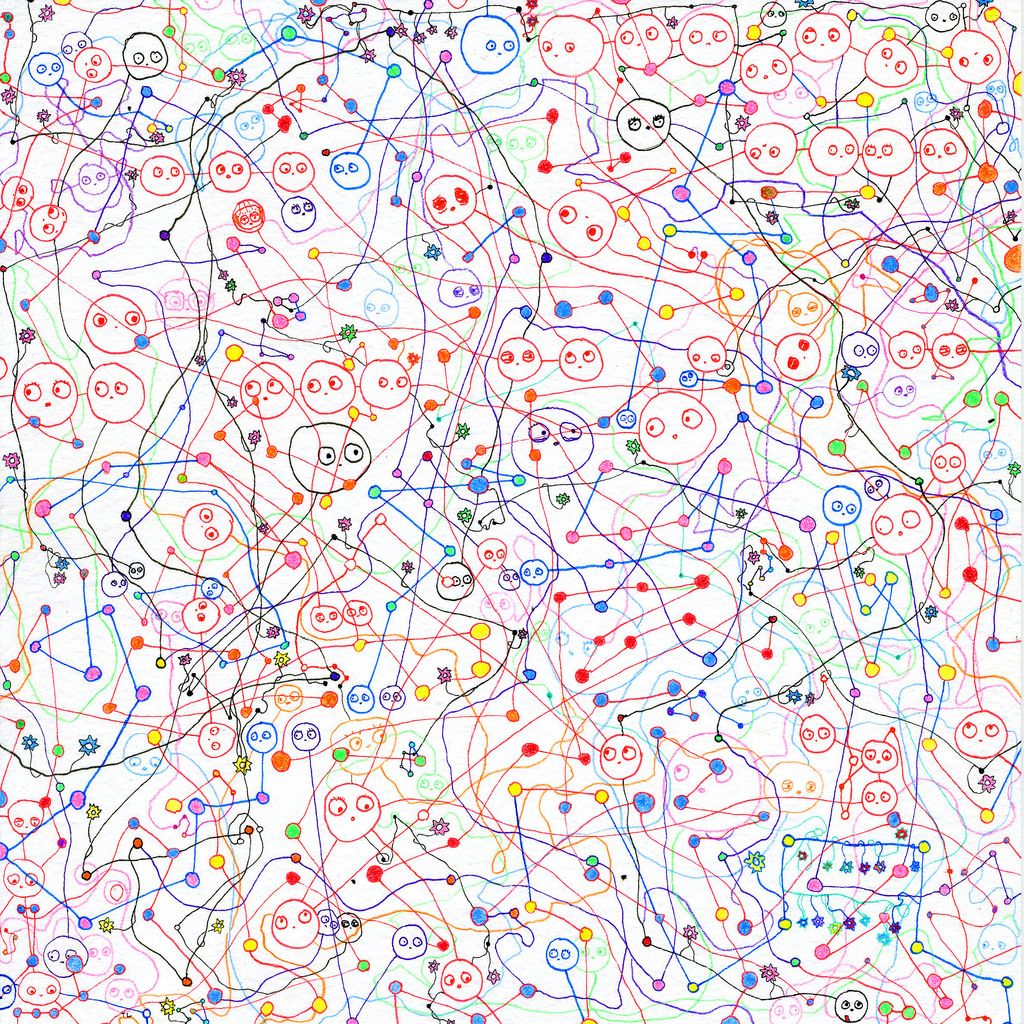

While on psychedelics, on psilocybin and DMT, I’ve encountered abstractions that felt like independent entities, but I haven’t interacted with them in any way I can remember besides on the level of what you quoted. But I also often grant inanimate objects, like pillows, the status of “independent entity,” and interact with them. I find the question of whether something encountered outside the universe is “real” or not frustrating and distracting. The word “real” to me just means “exists in the universe.” If something doesn’t exist in the universe, it’s not real. But, increasingly since 2012, I don’t think the universe is the only place. In other places—like the imagination—there are other things, with other properties, existing in other substrates other than matter and time, so the word “life,” like the word “real,” would be meaningless there, I feel. It’s known that the universe contains something which can be called “life.” Other places should contain other, different things, it seems.

But I do think that what we know of as “life” has probably made it unimaginably far outside and away from the universe—to possibly thousands of other worlds that are orders of magnitude more mysterious than the imagination, which seems to be the only other place that humans can normally access—because, among other reasons, Earth formed in an ~8 billion-year-old universe. I hope this answers your question in some way.

Many experts believe that 21st-century humanity is at significant risk of extinction, self-termination, or of catastrophically decimating itself and the biosphere. Do you have any thoughts on this, or on the topic of psychedelics and “saving the world”? Do psychedelics have a role to play in rendering us less likely to self-destruct at this critical juncture?

I like McKenna’s view on history, that it’s a brief, ~15,000-year transformation that becomes possible after billions of years of biological evolution, leading to a technology-using species, and that ends with the species transcending the universe—leaving the body behind—to enter the imagination. This could happen as an “emergent property”—it could happen suddenly at any moment, or start happening, with weird phenomena at first, in say 2023 or 2030, as humans achieve denser and more interconnected levels of global complexity; or it could be a technological breakthrough; or it could be that humans will leave matter via cosmic intervention from lifeforms that evolved billions of years before the Earth even formed and who sort of steward certain species into a higher dimension, as imagined in Childhood’s End(1953) by Arthur C. Clarke. Or, probably most likely, it will be something as-yet unimagined.

History is a process that is difficult and that can fail, though. McKenna stressed that we can’t return to grassland nomadism, or even before the 20th century, but we can make a “forward escape” into the imagination, leaving behind the planet as either a placenta (used up for a purpose) or a mother (a base for return and nourishment, as microbes served as a necessary substrate for plants, and both microbes and plants serve as a foundation for animals. In this view of life, psychedelics—but also many other things, like changing our food habits—can help in saving the world, with “saving the world” meaning making it deep enough into history to reach the end of time, because, among other reasons, when people use them, they get outside their culture, which at this point is most likely terrible and by default unhelpful.

If you appreciated this interview, I highly recommend reading Trip.

Jordan Bates

Jordan Bates is a lover of God, father, leadership coach, heart healer, writer, artist, and long-time co-creator of HighExistence. — www.jordanbates.life