Martijn Schirp • • 8 min read

This is Why You Should Go Watch The Psychedelic Movie “Embrace of the Serpent”

In this moment, it is not possible for me to know, dear reader, if the infinite jungle has started on me the process that has taken many others that have ventured into these lands, to complete and irremediable insanity.

If this is the case, I can only apologize and ask for your understanding, for the display I witnessed in those enchanted hours was such, that I find it impossible to describe in a language that allows others to understand its beauty and splendor; all I know is that, like all those who have shed the thick veil that blinded them, when I came back to my senses, I had become another man.

—THEODOR KOCH-GRÜNBERG, 1907

In his latest book, The Terrible Children of the Modern Age, one of my favorite philosophers Peter Sloterdijk asks us the questions, “aren’t we continually falling?”

Alarmed by the non-stop breaking of tradition, Sloterdijk asks us this question to address the fact that every consequent generation is more and more estranged from previous generations. With the increasing ubiquitousness of ever more powerful technology, he argues that larger and greater vectors pull life in different directions, with unforeseen consequences. Cyborgs, gene-modifications, artificial intelligence, to name a few.

We are moving further and further away from our roots and losing any grip we had on the quality of our traditions in the process.

We are no longer preserving the knowledge and wisdom of our tribes.

The result, Sloterdijk predicts, is the ruination of children. They have no way to navigate through chaos, yet, have no way to return to cosmos. They are lost.

This is perhaps the most important theme of this magnificent movie. People losing their way and bringing destruction to themselves and others in the process. Is the sacred plant combination a cure to our madness?

A few decennia before Sloterdijk, writing in the same critical tradition, philosopher Walter Benjamin urged his readers to listen to the voices of generations past. He asked us to consider the fact that our ancestors had very different wishes for us, but they lost a (cultural) battle, losing their history in the process. Now, their children’s children adopted their rulers’ rules, and forgot that their myths had been forgotten.

This is where we are today. This is the deep beauty of the movie Embrace of the Serpent.

Watching this story unfold, a deep longing awakens to return to what we have lost. A communion with plants, a silent dialogue with the other intelligences of our precious earth.

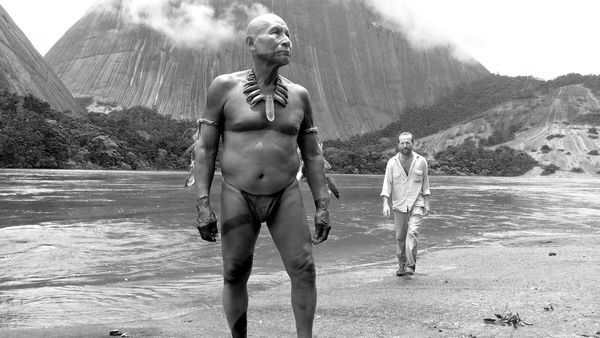

We see the world through the eyes of Karamakate, an Amazonian shaman-warrior who lives in cyclical time, and as the last survivor of his people, he carries the hidden knowledge of the psychedelic plant combination Banisteriopsis capi and Yakruna, which could potentially heal the spirit of the white and make them remember their place as the children of the earth.

The ravages of colonialism cast a dark and bloody shadow on the amazonian forest, exploiting, overpowering, and converting the indigenous people, destroying their communion with the plants in the process. There are few who are interested in the knowledge of the natives, but most notably, there are two scientists who, over the course of 40 years, built a deep friendship with Karamakate.

Embrace of the Serpent was inspired by the real-life journals of two explorers (Theodor Koch-Grünberg and Richard Evans Schultes). It is a story of friendship, loyalty, and betrayal and played by dozens of representatives from the different tribes that still dwell in the jungle. The filmmakers established a relationship of mutual knowledge and respect, being transparent in every negotiation and always remembering that this is their land.

“As we finished the first week of shooting, a deep concern came over me,” Guerra wrote in a journal, not unlike the ones of the explorers whose stories inspired the film. “The complications were too great, the schedule was too tight. It became clear, crystal clear, that finishing this movie was impossible. We had dreamt too big, we had aimed too far. We had been sinfully optimistic, and the gods and the jungle were about to punish us. With this clarity, like the sailor who is the first to notice that the vessel is sinking, I sat down and prepared for the inevitable. But then, what I witnessed was how a miracle came into being.

—CIRO GUERRA, writer & director of Embrace of the Serpent

It was pivotal this story was told from their perspective. The first of its kind.

And honestly, it shows. No exotic fetishism. No ‘wild savage’ hollywood obscenity. But a deep understanding and respect for the wisdom we so dearly lack.

Whenever I looked at a map of my country,

I was overwhelmed by great uncertainty.

Half of it was an unknown territory, a green sea, of which I knew nothing.

The Amazon, that unfathomable land, which we foolishly reduce to simple concepts. Coke, drugs, Indians, rivers, war.

Is there really nothing more out there?

Is there not a culture, a history?

Is there not a soul that transcends?

The explorers taught me otherwise.

Those men who left everything, who risked everything, to tell us about a world

we could not imagine.

Those who made first contact,

During one of the most vicious

holocausts man has ever seen.

Can man, through science and art, transcend brutality? Some men did.

The explorers have told their story.

The natives haven’t.

This is it.

A land the size of a whole continent, yet untold. Unseen by our own cinema.

That Amazon is lost now.

In the cinema, it can live again.

—CIRO GUERRA, writer & director of Embrace of the Serpent

This movie is a journey in itself. Through time, through live and death, through pain, joy and sorrow. Think Samsara meets Indiana Jones, but based on real life with a true message. As one reviewer beautifully put it: “It is a lament for all the lost plants and peoples of the world.”

Yes seriously, go watch this movie.

Interview with Ciro Guerra:

HighExistence: Where does this story come from?

It came from a personal interest in learning about the world of the Colombian Amazon, which is half the country, and yet it remains hidden and unknown, even though I’ve lived in Colombia all my life.

I feel that we’ve turned our backs on this knowledge and this way of understanding the world. It’s so underestimated, and yet so fundamental. But when you start to study and research it, you do it through the eyes of the explorers, who are always European or North American. They were the ones who came and gave us news about our own country.

I wanted to tell a story about these encounters, but from a new perspective, in which the protagonist wasn’t the white man as usual, but the native. This changes the entire perspective and renews it. We wanted to be able to tell this story in a way that was true to their experience, yet was relatable to any other person on the planet.

The story is told in two different times, based on the diaries of two explorers who never met. How was the process of writing and how did you find the narrative thread to tell this story?

There’s an idea in many of the texts that explore the indigenous world that speaks of a different concept of time. Time to them is not a line, as we see it in the West, but a series of multiple universes happening simultaneously. It is a concept that has been referred to as “time without time” or “space without space.”

I thought it connected with the stories of the explorers, who wrote about how one of them came to the Amazon following the footsteps of another explorer before him, and when he would encounter the same indigenous tribe, he would find that the previous explorer had been turned into myth. To the natives, it was always the same man, the same spirit, visiting them over and over again. This idea of a single life, a single experience, lived through the bodies of several men, was fascinating to me, and I thought it would make a great starting point for the script. It gave us a perspective of the indigenous way of thinking, but also connected with the viewer who could understand these men who come from our world, and through them, we could slowly begin to see the vision of the world of Karamakate.

With all that’s happened, how do you feel about the relationship with the native communities and how did they react to the production?

The native communities were very open and immensely helpful. Amazonian people are very warm, funny, with a lot of heart. They are obviously careful at the beginning, while they figure out what your true intentions are, because for a long time people who have come do so in order to pillage and hurt. But once they realize that you’re not a threat, they are very enthusiastic and we were very happy to work together with them.

What we are doing is rescuing the memory of an Amazon that no longer exists—that is not what it was before. Hopefully this film will create this image in the collective memory, because characters like Karamakate—this breed of wise, warrior-shamans—are now extinct. The modern native is something else, there is much knowledge that still remains, but most of it is now lost, many cultures, languages. This knowledge has been passed on through oral tradition, it’s never been written, and from my personal experience, trying to approach it was kind of humiliating, because it is not something you can aspire to understand in a short time like you do in school or college. It is related to life, generations, natural cycles; it really is a gigantic wall of knowledge that you can only admire and maybe try to scratch its surface.

The only way to learn it is by living it, and living it for many, many years. We can only hope that this film sparks some curiosity in the viewers: a desire to learn, respect, and protect this knowledge which I think is invaluable for the modern world.

It is not a matter of folklore or ancient cultures but of a wisdom that has answers to many of the questions that people today have: from how to achieve balance with nature, making the best use of its resources without ravaging them, and looking for harmony not only between man and nature, but between all the different ways of being human that exist. Reaching this equilibrium is a way to achieve happiness—a type of happiness that the current political and social systems are not capable of offering.

Has this process of research and knowledge of these cultures changed your perception of the world in any way?

In every way. I am a different person now than when this process started. I think all of us who made this movie feel the same way. You learn to swim in this gigantic flow and everyday it brings new things, new visions. We saw how everything has knowledge, from the rock to the tree, the insect or the wind, and we learned to find happiness in that. It’s a change in perspective.

It’s difficult for us, having been born and raised in the capitalist system, to change our lives. But we approached another form of existing, and it’s comforting to know that there’s not just one way to be human. Discovering the beauty in the other, and learning and respecting that, is still important.