Hans • • 22 min read

Enter Yoga: The Iyengar Techniques of Enlightenment

“As one Yoga teacher observed: Yoga has been reduced to fitness, more specifically stretching, and yet more specifically stretching of the hamstrings. This comment would be funny if it were not sadly true. While any approach to Yoga practice is a potential gateway to the real thing, there is clearly a continued need to emphasize that Yoga is a spiritual tradition, which seeks to bestow happiness and inner freedom rather than merely physical fitness and health.”

— Georg Feuerstein

“What has spread all over the world is not yoga. It is not even non-yoga; it is un-yoga.”

— Prashant S. Iyengar

Amsterdam, Sometime in 2018

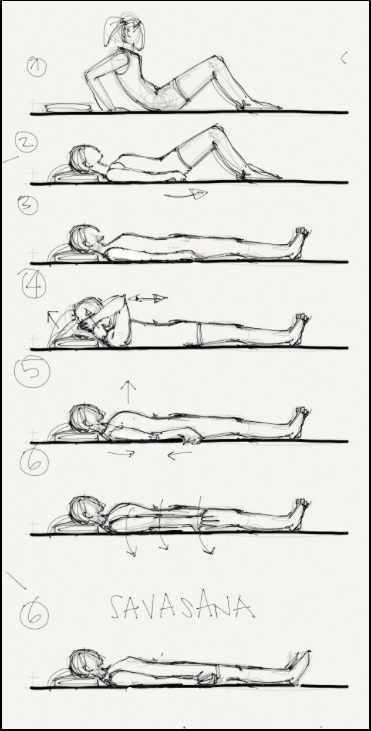

As I lay there on the floor I completely forgot where I was. I didn’t know that I was lying, or what a “floor” was, or who I was, exactly. There was a perfectly lucid sense of “I”-ness, but my sense of presence had no further qualifications beyond that it simply was.

I wasn’t having a stroke or anything like that.

I was doing yoga.

I’ve had this experience of “nothingness” several times now, in śavāsana, the final resting pose of a yoga session. I’ve experienced true silence—when the inner “self-talk” stops—in other yoga poses too.

I also sometimes have this upon waking up… a momentary lack of content in my mind (a slow boot of my cerebral hard disk?) where I don’t know who I am, but still feel like a “self”… just not like any particular self.

But the yoga-induced state of emptiness is an intentional result of this physio-mental discipline that’s been perfected, according to some sources, for over 5000 years.

And that time on the mat stuck with me, because a striking realization found me that afternoon:

“I dwell within”

I tell you, I am no Buddha. Far from it. But I find that as my yoga practice develops, I am beginning to experience what some of the ancient yoga teachers were talking about, and it is freaking liberating.

What yoga can offer is so profound, that not sharing it with you would be sinful. Arriving at yoga, however, was a winding road for me.

Coming from a university background of philosophy, I found that, within that all-too-academic realm of scholarly emancipation, phenomenology was the most “right” way to approach the world. The phenomenologists at least revered consciousness and lived experience. They would even call their writings “meditations”.

Even more interestingly, Husserl, one of phenomenology’s absolute behemoths, always was working towards unearthing what he called transcendental subjectivity—a concept of the higher (or deeper) Self that comes tantalizingly close to the Hindu concepts of buddhi (the intellect that is beyond the mind), and ātman (the self that is beyond the intellect). As we will see later, my philosophical interests were already leading me to a path of deeper self-understanding.

But for what I was seeking, philosophy was still too… bookish.

I yearned for experiencing something more direct, and so I delved into entheogens for a while. Working with ayahuasca still remains one of the most brutally unsettling Jungian deep-dives I’ve ever undertaken. Looking back on that phase, it was a period of profound upheaval.

Although I remain forever grateful to those encounters with my deep Self (and perhaps a few enigmatic plant spirits, a metaphysical question to which I’m disposed agnostically), I intuited it was time to ground down, and to learn to create stillness and stability through the daily spiritual practices of meditation and yoga.

The path is always cleared when you look back, even though it often takes gut-level choices in the opaque jungle of confusion when you’re in it. But looking back on this road so far, it makes sense that I did what I did then, and do what I do now.

Mindful of these (perhaps necessary) meanderings, and aware of the caveat that everything is not always for everyone at any given moment, my experience has nonetheless convinced me that the practice of yoga is one of the most potent paths to enlightenment there is.

Yoga… it’s real.

There’s a lot of misconceptions about what yoga is, though.

So for those that are confused, misled, curious or even already into yoga, I want to take away some of the haze surrounding this profound human art.

To do that, I want to show you how exactly yoga delivers on its spiritual pretentions. But mostly, I want to give it a fairer exposition than it’s often granted by those who misunderstand it, misrepresent it, or unnecessarily mystify it.

Hi, my name is Hans, Iyengar yoga teacher-in-training, and this is my meme-ified Apology for the Awesome Art of Asana.

Definition of Terms

[ “Enlightenment” – noun / ɪnˈlɑɪ·tən·mənt – the state of understanding something ]

“Awakening”. “Enlightenment”. These are some shady-ass terms when left undefined. So let’s do away with some of the vagueness right away: for present purposes, I suggest what we mean by “enlightenment” simply is the degree to which one has an unclouded perception of reality. To be enlightened is to clearly perceive life as it is and to not confuse it by what we imagine it to be.

[ “Yoga” – noun / ˈjəʊ.ɡə – a school of Hindu life-philosophy prescribing a regiment of physical and mental disciplines for attaining liberation from the material world, and union of the individual self with (the) Supreme Being ]

The word “yoga” is often reduced to meaning asana (the practice of yogic postures), which is only one part of the “eightfold path” of yoga. This “Ashta-tanga” (“eight-limbs”) of yoga is a complete, systematic and disciplined approach to spiritual liberation, that also prescribes “branches” (or “petals”) of ethical observations, pranayama (breath- and energy control), and different levels of meditation.

Here, however, I will focus on asana, when I’m talking about yoga, and I’ll use the 2 words interchangeably. But as the late Dr. Feuerstein indicated, asana should not be approached merely mechanically. The yogasanas are intentional postures, not gymnastics.

(small note: there are many more valid types and classifications of yoga [jnana, bhakti, karma, etc.] that I will not get into here for purposes of brevity. In this article, we deal with Patanjali’s “classical” yoga).The First Step on an Eight-Fold Path

So how does the path of yoga enlighten us?

Surely, enlightenment has to connect us to our innermost essence, from the first step on the way to that final liberation. And to reach it—even if that means some buddhistic realization of the lack of such an essence—we therefore must start from where, and what we are now: if we have an essence at all, then surely it must always be present with us.

What are you, right now?

What is true about all of us?

Are we fundamentally defined by our political disposition, or cultural heritage? By our sexual orientation? Or is it our philosophical ideas… our choices?

Of course these things define us on the surface, but not in depth. These identifications are still too sophisticated.

What defines us, basically, is the fact that we are living, breathing, embodied organisms. You can take away my convictions and I’d still have a body. You can take away my heritage, and I’d still be breathing.

I’m not saying we “are” our bodies. I’m saying we’re embodied.

And we have been such beings for eons.

That is the way in.

Meaning, spiritual enlightenment, i.e. profound psychological maturation, can only be achieved by us: living, breathing human beings. As the late yoga master B.K.S. Iyengar put it:

“As we explore the soul, it is important to remember that this exploration will take place within nature (the body), for that is where and what we are.”

Consider the stage set, then.

Combining examples from my own yoga experience with ancient Hindu texts and contemporary neuroscience, I will next elaborate on some of the yogic “techniques” that showcase its potency in bringing the light of awareness unto the dark veils of spiritual ignorance.

Meditation, With a Twist

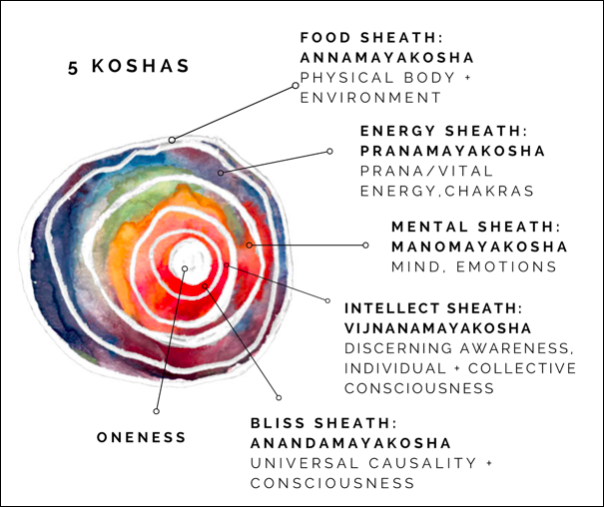

“Through the medium of attention, or present-mindedness, we can in fact integrate body and mind in any given moment. This is the process underlying meditation. It also is fundamental to the performance of yogic postures. This is why B. K. S. Iyengar was able to write that in the practice of āsana, the five “sheaths” (kosha) “come together in each and every one of our trillions of cells.” […] When these […] levels of our being are integrated through the medium of attention or mindfulness, āsana becomes what Iyengar calls a “contemplative pose.” Thus āsana, correctly performed, is meditation”

— Georg Feuerstein, The Deeper Dimension of Yoga: Theory and Practice

If yoga were a living being, meditation would be its body. Yoga is meditation. And meditation is yoga.

Or rather, yoga, at heart, is a meditative endeavour, and meditation is a fundamentally yogic exercise.

The operative principle of meditation-in-yoga is this: when you attentively execute an asana that arouses uncomfortable emotions, feelings or sensations, you will encounter all the strategies that your mind has towards not having to face them.

And it could be anything that triggers this mental mirror—even being “good” at a certain pose can bring forth your egoic patterns. But most acutely, what yoga reflects back at us, and makes us want to look (and go) away from during practice, are discomfort and pain.

Some examples.

Salamba Śīrṣāsana (“supported headstand”) often makes me afraid to fall. I can only do it correctly when I focus my attention on the correct movements and adjustments that the pose requires from my body. If I let the fear overcome me, I will definitely lose my balance. I have to keep it at bay.

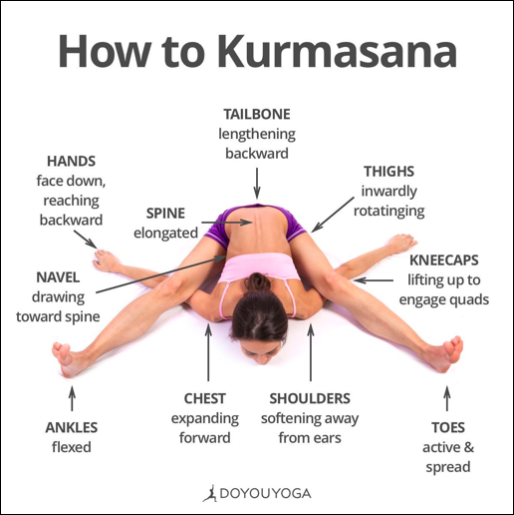

Kūrmāsana (“tortoise pose”) will make me self-aware of the fact that my peers can often go way deeper into the pose than I. I can only go deeper into the pose if I stop comparing myself to others (which by the way presumes overly objectifying both myself and those others) and keep my awareness grounded in myself.

Conversely, when I’m very comfortable with an asana, like Utthita Trikoṇāsana (“extended triangle pose”), I get hit with the fact that I can behave very arrogantly. You can imagine what vanity does to my awareness in the pose. Here, too, I need to be more centered in myself (which is, of course, the exact opposite of being “self-centered” in the way people usually use the term).

Such are the mental obstacles that I face: say hello to my ego.

Discomfort, and its bigger brother pain, are different species of hell.

We naturally fear pain. Its pull away from the present moment is much stronger than the other obstacles, although it could be argued that in essence, all the obstacles listed above boil down to different flavors of fear.

But fear can only grow in the absence of awareness in the present moment, i.e. it is a mental disposition. From my own experience, I would even argue that fear equals the lack of will to be present.

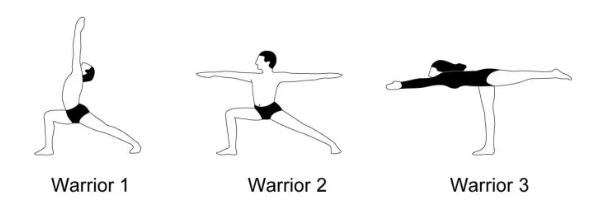

I’m reminded of something my teacher said when she assessed me for fitness to participate in the Iyengar Teacher Training. We were doing a difficult balancing pose (Virabhadrasana 3, in case you were wondering), and she saw me struggle.

What she then said, was exactly what I needed to hear.

“Don’t let the fear express itself”

We must accept fear, because it will be present in our minds from time to time. We just have to keep it from commandeering our actions.

I still often struggle to remain in a pose when my muscles, joints, and tendons are screaming at me to stop the pain. The blissful promise of ending the discomfort is tempting in those moments.

But the point is to keep engaging and practice surrender, for growth, by definition, can only take place beyond our comfort zone.

Working with forces like fear through asana reveals them to be powerful teachers on the yoga mat. And sometimes I do succeed in seeing these demons for the transitory entities they are, and I can stay with the pain or discomfort, and execute the pose with poise.

Fear, pain, discomfort, uncomfortable emotions, worried thoughts—when we witness their arising and falling with steady awareness, and when we are able to act correctly despite their presence, they lose their reign over us. We become equanimous.

In this way, the asana straightforwardly summons the mental obstacle into being. Performing the posture with unwavering attention, we breathe through—and subsequently overcome the obstacle by “breathily” maintaining the pose, as my teacher would say.

In this way, yoga can teach us to transcend our self-imposed inhibitions.

And just like that, the obstacle becomes the path.

When we meditate, the exact same thing happens: we learn to be mindful of whatever arises, and by mindfully breathing through it, whatever obstacle was there turns from a wall into a bridge, simply by maintaining awareness and accepting what is.

In asana, though, we do not wait for the devil to come get us; we manifest the beast ourselves, so we can conquer it through attentive surrender.

Yoga, then, is meditation for spiritual warriors.

Moreover, much like good music and silence go together, meditation and asana tremendously infuse and inform each other. Yoga prepares the body for prolonged meditation without (as much) physical complaints—one of the more obvious benefits of a steady yoga practice is the ability to remain still in difficult postures.

Conversely, meditation teaches us to be-with-what-arises in yoga. One of the more “fun” exercises we get to do in teacher training is that we sit, straight up, with a wooden block between our sitting bones. I tell you, there are more pleasant feelings on this planet than this square hell—like having your leg amputated without anesthetics.

But during one such block-sitting-extravaganza’s, I remembered the pain I’d felt during a Vipassana meditation retreat (a tradition which coicidentally shares some of its roots with Iyengar yoga), and that I’d sat through that without flinching (well, like 98% flinchless, anyway).

“If I can do that”, I realized, “I can do this”.

And so I did.

Ever since I made that meditation connection, buttock-bones-block-sitting no longer fazes me.

In meditation, we are mindfully passive; in yoga, mindfully active. Their essence is the same, and like yin and yang, they revolve around the common spiritual center of true Self-knowledge.

Freedom

Even more awesome than transforming mental roadblocks into spiritual gurus, the true fruit of the practice of yoga is that it can free us from ourselves.

In yoga, we address the dichotomy between body and mind by training with focussed awareness to make distinctions between what is mental and what is physical.

For instance, you think you can do a certain asana, but you cannot; you think your body can’t do a different asana, but you merrily find out that it can.

Awareness in the body thus corrects the mind.

The goal of asana practice is however not to go away from the mind and towards the body—even though for many of us, this is an important first step—but rather to balance the two.

There is this sort of calibrating-dialectic in asana, between our physical and mental aspects, by which we gradually start to see through the illusory limitations that the mind superimposes on the body.

We find that we have a mental image of our body, in other words, that does not correspond to the felt experience of the body.

Through this “primacy of perception”, asana generates awareness in the body, while at the same time connecting our minds more strongly to phenomenal reality.

What I realized is that this awareness-training through the body leads to a freedom from the body.

Let me unpack that.

I see two kinds of freedom that yoga brings: firstly, becoming more flexible & able through asana practice literally frees you up in the sense that you will have a greater range of motion, flexibility and stamina, arguably constituting the most directly meaningful sense of freedom imaginable: unhindered physical ability.

But secondly, and more interestingly, you will become free of identification with the body itself.

The benevolent wisdom of Eckhart Tolle helped me to realize this truth. In one of his talks he guided a question-asker into understanding that every pattern of behavior you do not recognize as a pattern, becomes (part of) your identity.

That statement might need some elaboration.

Shades and Flicks

When we identify with consciousness itself, it then follows that what we are aware of, is not us (“not-self”).

If you’re wearing sunglasses, say, you obviously can’t actually see them until you take them off.

Similarly, what you cannot (yet) separate from and observe psychologically (like behavioral patterns), functions as a part of you, in much the same way that you see through the shades that you’re wearing, without noticing them.

When this lack of separation from—i.e. attachment to—sunglasses becomes unconsciously-habitual, you no longer see the shaded world as something that could be less opaque.

This means that that-which-mediates between (a) pure consciousness (the glasses) and (b) that-which-is-perceived by it (i.e. something in the world), they get mixed up, and we are unwittingly operating from within an existential situation of attachment.

This might seem relatively innocuous, but it is in fact the very root of unhappiness.

Wearing shades unknowingly, you now have a less pure view of the world. Like a “world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth”, to quote a contemporary guru (it is perhaps ironic that Morpheus wears sunglasses).

It then follows that we have to take away our blindfolds (or glasses) in order to break free from attachment.

More generally, Tolle’s repeated message is for us to break free from identification with forms: outward, “external”, seemingly steady-through-time objects.

He urges us to see through this illusion of lasting forms and to realize that every single such form has a transient existence, ever morphing—however slowly—into some different expression of being.

In this sense, there are no fixed objects or forms in the world at all, when you look at the world without attachments to it.

There are only processes.

And so, everything that comes in to and out of being in this way, is not the unchanging—what the Buddha called the “undying”—dimension of the true Self. It is this true self that is the only “self” that is unattached to anything.

Tolle sometimes calls this type of awareness “space consciousness”, to emphasize the no-thing-ness of that mode of being. Mystical though it may sound, this simply means to have an awareness of the difference between consciousness and the things that occur within consciousness, like the movie screen and the movie, to invoke another metaphor.

The movie screen itself is unaffected by the movie, but the film displayed grasps our attention completely. We forget the unmovable screen behind it, because we’re enthralled by the cinematic illusion.

In the same way, the unending kaleidoscopic machinations of the mind keep us attached in the field of karma, i.e. of ups and downs, happiness and sadness, good and evil. To detach from that illusion is to be free of the throws of life.

Eckhart Tolle teaches us to identify with the screen and let the movie be. To abide equanimously as consciousness itself, and to let the flow of forms come and go as they will.

This is all to say, that when I realized “I dwell within”, I applied Tolle’s lesson to the body.

When you recognize your body as your body, by being aware of its sensations, you can stop identifying with it as yourself, and start seeing it as something you are aware of.

Yoga, as you by now have guessed, illuminates such recognition.

As awareness dissolves attachment, the body becomes a vessel. Embodiment slowly shifts, for the yogi, from being a body to having a body.

How can this happen?

What asana does is it creates a dialogue between the mental dimension and the physical, making us more aware of both realms. In doing so, it thematizes their mode of being before our conscious awareness, and presents us in this way with their essential differences.

I.e., when I’m doing a downward facing dog, for instance, I am simultaneously aware of:

- what my body is doing;

- what I’m supposed to be doing with my body (heels down, knees up, thighs back, hands press down, abdomen in and up, upper arms roll in—and the list goes on);

- what I am thinking about all this

I am able, thus, to separate what is a thought, from what is experienced reality and further, from my will (or aim).

It’s precisely this distinguishing act between the “modalities” of consciousness (i.e. physical vs. mental awareness) that produces the removal of self-identification.

This is then to say that, when we are thusly sensitized through yoga, we learn to identify with the very conscious awareness itself, that dwells inside the body, that is itself neither mind, nor body.

The body-mind dialogue that is asana, in other words, presents us with its medium. And what mediates between body and mind—their unifying principle—is consciousness itself.

…Meta-consciousness, if you will.

This higher-most Self in Hindu wisdom traditions is called “ātman”, the individualized drop of awareness, that is connected to the oceanic “Brahman” as its ultimate, universal source.

This holy relationship between the individual and the Universal of existence is what Rumi alluded to when he said “you are not a drop in the ocean. You are the entire ocean in a drop.”

Here we arrive at yoga’s central process: by becoming more aware of the mind and more aware of the body in this way, we become meta-aware of this awareness itself.

Thus emerges a “spiritual” dimension of awareness that supersedes both mind and body in its freedom from identification with either: I am not my body and I am not my mind—the body structure and the mind structure are more like the spaces in which my consciousness resides, and between which it can move.

In yoga, the mind and the body are recognized as layers of shadows, or “sheaths” [kośas] that cover the innermost ātman. And like those “reverse” sunglasses, they cover our inner light.

The more sunglasses you can recognize as sunglasses and can subsequently take off (yoga recognizes 5 kośas), the less opaque—the more transparent—your perception of reality becomes.

This is the path of yoga. This is also why Mr. Iyengar, a.k.a. “guruji”, called his greatest works “Light on life”, “Light on Yoga”, “Light on Pranayama” and so on.

This enlightened kind of awareness is what buddhists call emptiness: it is empty of self-identification.

Keeping to our intention to demystify enlightenment, we should then ask: what does it mean to be “empty of self-identification”?

“A finger can never point to itself, just as the eye can never see itself”, Alan Watts would say.

Self-reference, in other words, is ultimately realized as an impossible illusion, and so our image of ourselves—the ego—dissolves.

Seeing through the structures that consciousness inhabits enlightens us to the reality that consciousness is essentially formless, structure-less, and without fixed properties.

The Self, unhinged from any attachment to form or identity, roams free.

To realize such a free state is called samadhi, the full unifying immersion into the cosmic frequency, the final limb of the Ashtanga of yoga, where ātman merges with Brahman, and self-seeking collapses into self-realization.

in a non-dualistic understanding of what is described above, we can finally say that, in yogic samadhi, we realize not just that consciousness resides in the body/mind, but that it is what the body/mind is made of.

(psst… do check out Rupert Spira’s nondualistic teachings for some glorious Advaita Vedanta mindfucks!)Who’s Behind the Wheel?

I realize all this talk of “sheaths” and “Brahman” might sound somewhat metaphysical. But I’m not theorizing about what could be; I’m attempting to show you how my very own experience of yoga is congruent with the ancient yogic texts.

Moreover, those texts are meant to be read phenomenologically–as experiences of the self–and not entirely mythologically. They are primarily descriptive, rather than explanatory.

As Stanislav Grof, one of the founding fathers of transpersonal-psychology and a Hinduism connoisseur sees it, the Hindu texts should be regarded as maps of the subconscious. These maps, because of the “psychological” depth of what they point to, have to take poetic form, as mythology buff Joseph Campbell explains:

“Mythology is not a lie, mythology is poetry, it is metaphorical. It has been well said that mythology is the penultimate truth–penultimate because the ultimate cannot be put into words. It is beyond words. Beyond images, beyond that bounding rim of the Buddhist Wheel of Becoming. Mythology pitches the mind beyond that rim, to what can be known but not told.”

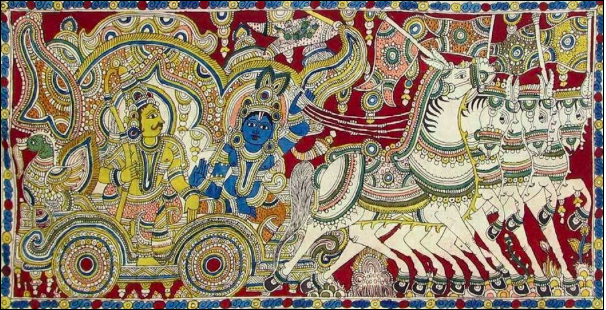

One such Hindu text of particular interest is a certain passage of the Upanishads involving the major Hindu deity Kṛṣṇa (Krishna) and the human Arjuna.

Here we see Arjuna (left) and lord Krishna depicted in the chariot. In the Katha Upanishad (verses 1.3.3–11), the chariot is used allegorically to depict the composite concept of the individual: the horses are his senses, and “the roads they travel are the mazes of desire” (ever ate that extra burrito you really didn’t need but couldn’t resist that mouth pleasure? That’d be them needy steeds).

The mind, specifically that part of the mind that is engaged with those senses, is represented as the reins, and the intellect (the “buddhi”) is shown as the charioteer. The chariot itself is the body, and the Self (ātman) is the rider inside of it.

(I dwell within)The Bhagavad Gita, another canonical yogic text, brings a clear hierarchy to all these layers:

“The senses are said to be higher than the sense-objects. The mind is higher than the senses. The intelligent will is higher than the mind. What is higher than the intelligent will? The ātman Itself” — (Bhagavad Gita 3:42)

This metaphor can thus be understood as a phenomenological schema of the different strata of awareness and its layers of attachment to the world. The upanishadic chariot allegory, not to be confused with Plato’s chariot allegory that also metaphorizes the soul, circumscribes the way our consciousness gets entangled with its various carriers/media/vessels/koshas/layers of embodiment.

This is why, when one forgets that the Self is the master of the chariot, the intellect becomes entrenched in the karmic world of action-reaction. The path of yoga, being a contemplation on the Self, reveals the true Self to the yogi, by revealing its existence beneath the structured layers that cover it.

Such is the wisdom of the ancient civilization of the Indus valley.

YEAH, SCIENCE @#%*&!

But for those that demand scientific evidence, there’s that too.

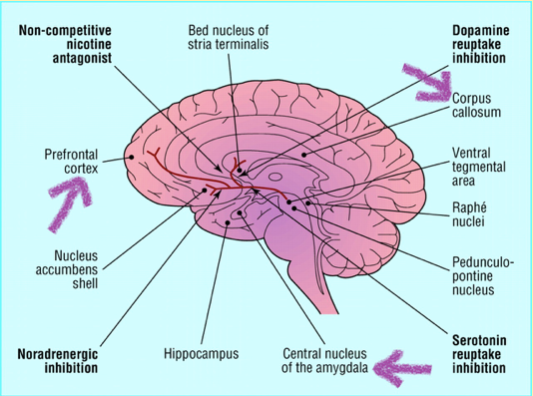

It has been shown that prolonged immersion in meditative states produce increases in the connections between the left and right hemispheres (in the corpus callosum), arguably leading to a better integration of our creative and logical personality aspects.

In December 2018, BrainWorld magazine stated: “We used to believe the two parts of the brain work in harmony, but according to London psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, there’s a definite shift in our modern culture which favors left-brain dominance—and it’s something we ought to watch out for and correct.”

McGilchrist had a particularly profound discussion on this topic with Jordan Peterson, but suffice it so say for current purposes, that integrating these left and right “personalities” inside our head, by making the corpus callosum more interconnected through yoga, might just be the physiological manifestation of the Buddha’s Middle Way—or Taoism’s deepest truth, as Peterson seems to argue.

The amygdala, associated with fear and emotion, shrinks, resulting in a more balanced and less stressed emotional life. And perhaps even more interestingly, the prefrontal cortex increases in its number of connections.

The prefrontal cortex is, among other things, associated with morality, executive function, decision making, impulse-control and meta-cognition. There are other brainy things happening through yoga, but you get the idea.

Furthermore, certain “inverted” poses like supported headstand, according to the Iyengar method, are even said to balance out the hormonal system by acting on the endocrine system that regulates hormones, providing even more balancing goodness to the yogi’s mental state.

These brain-changes represent, to my estimation, nothing other than the scientific correlate of what’s being described in the chariot metaphor.

Yoga can increase our meta-awareness and give the yogini a stronger reign over her mental- and behavioral patterns (prefrontal cortex action), it can help increase emotional balance (amygdala action), as well as stimulate a more integrated personality (corpus callosum action).

And so, as her actions become more and more infused with consciousness, and her motivating drives more transparent to her, the yogini will sense a greater degree of freedom from reactive patterns that used to control her.

More and more, she becomes the unmoving master in the chariot, seeing through the causal relations between the (re)actions of the horses, the reins, and the charioteer. Her inner “buddhi” awakens to its true Buddha nature.

These changes are real, but often incremental.

As an example from my own life, I have sort of a coffee dependency. I love the taste and especially the kick, but some addictive tendencies in me make it very hard to limit my intake.

But I notice very clearly, in periods where I do a lot of yoga and/or meditation, that all of a sudden there is this ever-so-subtle “space” that emerges, a space between that addictive drive and the subsequent semi-automated motor patterns that direct me toward the coffee machine.

It is in this space that I am able to realize—to see—the pattern, and choose a different action.

This possibility, modest though it may seem, is nothing less than the experience of freedom.

I don’t know about you, but freedom is the closest approximation of the essence of divinity that I am able to imagine.

This divine space, then, in which I realize my “highermost self”, as something beyond any pattern of behavior, or any structure of embodiment, is the blissful fruit of my yoga practice.

But don’t just take my word for it, nor, for that matter, even that of all this science. Nothing verbal could ever say what it is like to do yoga. As that wise old pill-carrying sun of a gun once said, “you have to see it for yourself”.

Yoga, for all its philosophy, is emphatically not academic. As Dr. Geeta S. Iyengar said, “It is your practice that brings the secrets to you”.

And should you decide to give it a go, or even when you already practice yoga, I cannot recommend strongly enough that you specifically try Iyengar yoga. It really is that good.

Iyengar Yoga

Of course, other schools of yoga can be awesome too. They might be just as potent as the Iyengar way, or they might simply work better for you.

As the great late teacher Geeta Iyengar observed:

“Gaining maturity in yoga practice involves learning to respect the paths that other people are on and acknowledging their merits, maybe even acknowledging that your own path is lacking in some area where another one excels.”

Heeding these wise words indeed, I couldn’t possibly judge all yoga styles, nor would I want to.

But I sure can vouch for this one, and comparisons can be made.

Developed and introduced to the world at large by B.K.S. Iyengar, this breath- and asana-focused yoga form has influenced damn near every other style that exists today, while still being one of the main branches of yoga practice itself.

Iyengar yoga is brutal. It’s spartan. And it’s anatomically exact.

It is exactly that attention to physical, physiological, and mental detail, combined with a never-ending attention for the breath, that makes Iyengar yoga such a great remover of spiritual flakiness. Because it allows for no escapes.

When every little part of your body has a task to perform in every single moment, awareness is affluent.

Discomfort, self-confrontation; they are pretty much guaranteed on the Iyengar path. It will present your obstacles to you, and the means to breathily dissolve them into emptiness.

And it will introduce you to your body so completely, that you just might come to see it as a vessel you inhabit.

So as a dear friend once asked me:

…What is your body to you?

~ Additional note, August 2019 ~For those interested in an accessible way of learning more about yoga, its history, its many forms, and above all, its true depth and purpose, I highly recommend Feuerstein’s book The Deeper Dimension of Yoga: Theory and Practice.

We get no money or any other compensation for endorsing this book. It is simply my own personal opinion that is is an absolute must-read for any yoga lover or anyone interested in the subject. Namasté!