Jordan Bates • • 13 min read

4 Things I’ve Learned While Living in a Cabin on a Commune in Canada

26 days ago, I arrived at Boldairpur, a commune in Quebec, Canada, about ~90 kilometers from Montreal, where I will be living in a cabin for a total of three months.

Your first question might be: How did you find that place? It was surprisingly simple. I searched for cabins for rent for under $500/month on AirBnb. I found zero such places in the entire United States, but a search of Canada revealed ~15 options or so. I quickly honed in on Boldairpur, which looked perfect, and booked the place within a couple days.

An Overview of Boldairpur, the Commune on Which I’m Living

Established in the 1980s, Boldairpur exists on a beautifully secluded 480-acre patch of forest which doubles as a maple syrup farm. There is a lake here, as well as a river running through the property. There are endless snow-draped trees and about 30 hermitages/cabins sprinkled across the land, one of which I’m occupying. There is also a large central building known as “Le pavillon D’accueil,” which I think translates to something like “The Hospitality Pavilion.” This building serves as the primary communal/congregation space for the ~10 permanent long-term residents of Boldairpur, as well as any guests (e.g. me) that happen to be staying here.

The Pavilion is kind of like an enormous home, complete with huge dining room tables that could comfortably seat 40-50 people; a living room with numerous comfy chairs and couches and a big TV; an office; a number of bedrooms; a large and gorgeous kitchen; a self-serve bar; fast WiFi (praise the Heavens!); a sizable bathroom area with multiple showers and sinks; and a vast upstairs sanctuary-ish room reserved for meditation and prayer. The Pavilion is also connected to a kind of workshop where the maple syrup production takes place. There are long black hoses snaking throughout the land which transport maple water to the workshop to be boiled down into delicious syrup. This year’s maple syrup production began a couple weeks ago, so I’ve now had the opportunity to sample the fresh maple syrup, and Holy Oceanic Cosmos, that stuff is good.

So, uh, yeah, if you read “commune” and envisioned a bunch of vagabonds living in shanties and subsisting on fire-roasted roadkill, you’d better revise that stereotype. The spectrum of intentional communities in the world is wide and diverse, and this particular commune is definitely on the more upscale end of things. Honestly, it’s pretty damn idyllic.

What Exactly is a Commune?

It might be a good idea to address this question, especially since my mom’s reaction to my mentioning the word “commune” was to ask, “It’s not a cult, is it?” *Sighs.*

When I think of a commune, I think of a group of people living together in some kind of intentional arrangement, sharing resources and living in such a way as to have a low ecological impact. And, after some preliminary research, it appears that my definition is basically correct, if slightly incomplete, depending on who’s defining the term.

According to Wikipedia, “commune” is a French word that first appeared in the 12th century. It was derived from the Medieval Latin term, “communia,” which referred to a large gathering of people sharing a common life. “Communia,” in turn, was derived from the Latin word “communis,” meaning “things held in common.” From Wikipedia:

“A commune… is an intentional community of people living together, sharing common interests, property, possessions, resources, and, in some communes, work and income and assets. In addition to the communal economy, consensus decision-making, non-hierarchical structures and ecological living have become important core principles for many communes. Andrew Jacobs of The New York Times wrote that, contrary to popular misconceptions, ‘most communes of the ’90s are not free-love refuges for flower children, but well-ordered, financially solvent cooperatives where pragmatics, not psychedelics, rule the day.’”

By that definition, Boldairpur qualifies as a commune. I’m not sure how the income and assets are divided here, but everyone who lives here seems to have similar interests and principles that bind them together, and residents share the whole of the property, possessions, and resources. The power structure seems to be totally non-hierarchical, and there is a strong environmental/ecological ideal present as well: Everything is recycled. All water comes from underground wells. Some of the cabins have compost toilets. And the group has plans to erect a greenhouse in the near future to begin growing a substantial portion of the food they consume. Again, from Wikipedia’s article on communes:

“Twenty five years later, Dr. Bill Metcalf, in his book ‘Shared Visions, Shared Lives’ defined communes as having the following core principles: the importance of the group as opposed to the nuclear family unit, a ‘common purse’, a collective household, group decision making in general and intimate affairs. Sharing everyday life and facilities, a commune is an idealised form of family, being a new sort of ‘primary group’…”

This emphasis on the importance of the larger group or community, as opposed to the nuclear family, certainly seems to be present at Boldairpur. There are no children here at present, and as far as I know none of the long-term residents have spouses living here. All of the long-term residents are in the latter years of middle age or older, and the group is very tight-knit and affectionate. It’s clear that these are old friends who have built something very special through decades of living and working together.

(Also, for the record, I am not a communist. Yes, one can be interested in communes/communal living without subscribing to any particular political ideology. I think the communist model of common ownership/non-hierarchy can work well in a microcosm such as Boldairpur, but I see a number of issues [which I won’t get into here] with imposing such a model onto an entire society with tens or hundreds of millions of people.)

My Ongoing Experiment in High-Autonomy Living

Hopefully that was an enjoyable introduction to Boldairpur and a useful ‘Communal Living 101’ crash course. This subject is of great interest to me, as I’ve dreamt for years of escaping the normative models of life and work passed down to me by my society. It’s always seemed to me that there must be alternatives to the dominant paradigm of resigning oneself to 4-5 decades of ~40-hour weeks at a dull or vexatious job.

And, to my delight, there are. For one, of course, there are actually plenty of jobs within the existing system that aren’t dull or vexatious. At some point, I might return to the world of normal work to try to become a professor, or to work for an Effective Altruism organization, or something like that.¹

Since graduating university with an English Lit degree in 2013, however, I have concerned myself primarily with finding ways of escaping the existing system or working at its fringes. I’ve made it my priority to have a high-autonomy lifestyle because I value freedom more than most anything else.

I taught English in South Korea for one year almost immediately after graduating university, and that experience opened my mind to the galaxy of possibilities for working abroad. After 16 months in Asia, though, I felt ready to return to my home country, so I moved to San Francisco and took a job as a transcriber of online, video-based course content at an art university. It was a pretty good job, as far as day jobs go, but it was also quite tedious and not particularly challenging.

Luckily, around the time I took the job at the art university, I got an email from Martijn, the co-founder of HighExistence, offering me a job at this website. I took the job, working it part-time while also working at the art university, and in September of 2015 I quit the job at the art university to work full-time for HighExistence. I’ve been living the digital nomad lifestyle since then.

In recent months, I’ve also been fortunate to experience life in multiple intentional communities. I lived for about 3.5 months in a kind of adult-playground/co-working house² in San Francisco that had anywhere from 5-10 people living or crashing within it at any given time. That was one hell of an experience that I’ll probably elaborate upon in future writings. And, about six weeks ago, I had the privilege of staying with an online friend in Los Angeles who lives in a communal situation involving two adjacent houses and a large shed with ~7 other young people, several of whom are members of the band GoodKids and most of whom met one another in the USC music department. That too was a wild and memorable experience.

Both of the aforementioned situations had a major impact on my thinking regarding communal living. I felt firsthand the amazing and intimate vibes and bonds that can arise between a good-sized group of people who share/create an environment, and I’m quite keen to visit/experience/create more intentional communities in the future.

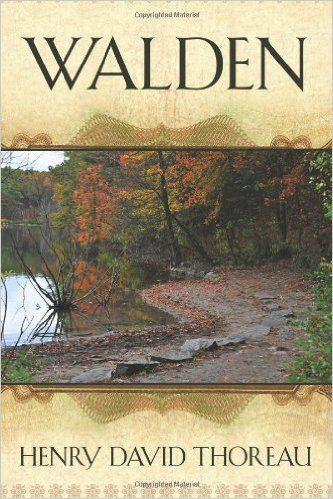

I’ve also dreamt for some time of “pulling a Thoreau” and vacating society to live in a cabin for a period of time. I love the serenity of the natural world and have often felt that a simple existence in a small house in the woods would suit the introspective, solitary, creative side of my personality.

Boldairpur is a decidedly good fit for me, then, as it fulfills both my desire for communal living and my desire for cabin-based, solitary living. I have a cabin all to myself and can retreat there at any time to be alone, or I can spend as much time as I want in the Pavilion, socializing with my newfound friends and fellow commune inhabitants. So far, this arrangement seems mighty fine.

I hesitated a bit before writing this article because I’ve only been here for 26 days, and like, “Bro, what could you possibly have learned in just four weeks in a cabin on a commune?” It’s true: I haven’t been here all that long at all, and I’m sure this place has much more to teach me. Nonetheless, I do feel that a few lessons are already beginning to take shape. I also wanted to write an introduction to my experience to gauge interest.

So, without further ado, let’s get on with the stated intention of this article, which is to share 4 things I’ve learned so far while living in a cabin on a commune in Canada.

4 Things I’ve Learned So Far

1. You don’t need dogma to be deeply spiritual

One of the most refreshing things I’ve learned so far about Boldairpur is that although there is a strong spiritual ideal present here, the residents don’t believe in adhering to a single ideology or dogmatic belief system.

One resident, my friend Carold, explained to me that from his point of view, all of the world religions have valuable wisdom to offer us. He observed that as soon as one decides that one religion or ideology is “correct,” one has also decided that every other point of view is “wrong,” sewing the seeds of antagonism and potential conflict.

We also discussed the way in which organized religion can prevent individuals from experiencing the sacred for themselves and developing their own unique relationship to the cosmos. “God is for everyone,” Carold told me. While I’m not certain what Carold means when he says “God,” I generally agree with his sentiment.

It’s refreshing to discover that a non-dogmatic, freethinking approach to spirituality is in favor at Boldairpur. My approach is very much the same, and it’s always encouraging and educational to encounter others on a similar path.

2. Total isolation without Internet or phone plan = creativity paradise

As I mentioned, the Pavilion has Wifi, so that’s where I go to accomplish my work for HighExistence. In my cabin, however, I have no Internet. I also cancelled my phone plan, so I can’t receive any texts or messages or Snapchats or *anything* when I’m posted up in my modest dwelling.

It turns out that this is the absolute best way to increase my creative output by an insane amount. On one recent night I wrote ~3500 words in the wee hours of the morning — something I never do because I’m always deep in Reddit or Twitter or Facebook or whatever it is. I also literally worked ~50-60 hours in a single week on my music, which is by far and away the most time I’ve ever spent on music in a 7-day period. Usually my weekends are devoted to social activities, but since I’m isolated from literally everyone I’ve ever known in this world, they’re now free days for nature hikes or marathons of creative output.

And every weeknight, after work, I return to my cabin to find myself in a realm of zero digital distractions, which seems to put me in an entirely different thought-space. I start wondering what I can create, instead of thirstily scrolling through endless newsfeeds. So I’ve literally been writing or working on music late into the night every single night. I’ve also been reading tangible books again (currently reading The Places That Scare You, 1Q84, and Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, and they’re all great).

Some nights I’ve taken breaks here and there to watch a pre-downloaded episode or two of Rick and Morty, but for the most part, my cabin has been a creativity oasis. I’m now thinking that if I ever need to complete a big creative project or learn an entirely new subject or skill, I will ideally retreat to a cabin or at least to some place with no Wifi and no phone plan that is far away from everyone I know on Earth.

3. No grocery stores, convenience stores, or restaurants = weight loss

There are no fast food restaurants or 711s for miles around here, and I don’t have a car, so I’m not even tempted to buy convenient, unhealthy food, which is something I do too often when I’m living in any decent-sized town or city.

I didn’t have a fridge for the first ~24 days here either, so I stocked up on rice, oatmeal, cereal, peanut butter, honey, raisins, prunes, nuts, and tortilla shells before coming out here and have been eating mostly that stuff. There are also delicious meals cooked up everyday at the Pavilion that I can buy, but I’m on a budget so I’m only eating dinner there 2-3 times per week or so.

I can already tell that this situation is downsizing my belly. Pants and t-shirts are noticeably looser. I expect I’ll probably cut 10-15 lbs while living here.

4. True silence is a rare and valuable commodity in 2016

One of the first things I noticed upon arriving at Boldairpur is how silent it is out here. Apart from the whispering wind and an occasional plane overhead, there are very few sounds. It’s kind of surreal, especially after living in cities for the last couple years.

When living in the city, one becomes accustomed to ignoring an ever-present hum of background noise. Although it’s fairly easy to put this noise out of your conscious mind, its presence still has subtle effects on perception. The endless buzz keeps the mind forever aware on some level of the city’s only mode: endless activity. This awareness, I think, results in a subtle, base level of anxiety — a sense that one needs to be moving, doing something, taking care of business.

Read this: 11 Takeaways From 8 Months of Unemployed Nomadism

It’s fascinating to strip away that background noise, if only for the refreshing experience of a truly quiet environment. So far, this novel silence seems to be helping me to relax, move slowly, notice other aspects of the natural world around me, and get in touch with my fundamental drives and desires.

In Sum

So that was a fairly in-depth summary of the basics of communal living, my ongoing experiment in high-autonomy living, and my experience thus far living in a cabin on a commune in Canada.

Hopefully you found some useful/fascinating food for thought and/or inspiration in this post. If you appreciated it, drop a note in the comments to let me know or to share any thoughts. If many people dig this post, I can surely write more about my experiences. Peace out, everyone.

Recommended Reading — Walden by Henry David Thoreau

If you appreciated this post and want more insight into simple living, you’ll love Walden, Henry David Thoreau’s classic account of the two years he spent living in seclusion in a small house near Walden Pond. I read this book in college, and it had a major impact on my thinking.

“In 1845, Henry David Thoreau moved into a cabin by Walden Pond. With the intention of immersing himself in nature and distancing himself from the distractions of social life, Thoreau sustained his retreat for just over two years. More popular than ever, Walden is a paean to the virtues of simplicity and self-sufficiency.”

Footnotes:

- This is written as if I will definitely, for the rest of my life, have the liberty to choose whether or not to return to the world of normal work, which isn’t necessarily true. It’s possible that my entrepreneurial quest will crash and burn and I will be forced to take a job I don’t really care for to pay the bills. It’s also possible that large, unforeseen expenses could arise that my current income wouldn’t be able to cover. Ideally, these things won’t happen, but I don’t know that.

- Several of us doing computer-based work would often work in the common area of this house, and it was also a kind of think tank in which I had many of the best and most stimulating conversations of my life. It was definitely a “work hard, play hard” type of environment, though. The house had an indoor swing, retractable roof, multiple guitars, a drum kit, a keyboard, multiple sets of large speakers, Nerf guns, bean bags, a projector, many video games, a chihuahua, and an unbeatable view of San Francisco and the surrounding Bay Area. It was common practice to ingest nice beer, among other things. I will forever remember that house as a utopia.

Jordan Bates

Jordan Bates is a lover of God, father, leadership coach, heart healer, writer, artist, and long-time co-creator of HighExistence. — www.jordanbates.life