Alexander Blum • • 7 min read

Carl Jung and Culture War: How Our Shadow Creates a World of Enemies

“Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves.”

— Carl Jung

Evil is not a force to be destroyed in the external world. Each waking moment, evil is closer to us than our own beating hearts.

No honest human being could deny the voice within that is an unseemly double, the whispering “no” to oppose our every conscious affirmation of life. In Christian mysticism, two is an unseemly number – it reflects how truly split our consciousness really is. Our adversary, our antichrist, is just a mythologization of that split psyche.

The problem with Christianity, for Carl Jung, was its attempt to hide the reality of the shadow. In Aion, Jung describes the shadow as “the face of absolute evil”, the projections and emotions which constitute all the “dark aspects of the personality”. Early Christianity, in an attempt to banish evil from its cosmology, defined evil as the mere absence of good. Augustine and the Early Church fathers believed that evil, unlike God, has no real substance. Jung found this definition to be a comforting illusion. Evil asserts itself endlessly across the landscape of human thought and history. It is wishful thinking to suppose that evil has a lesser place in the cosmos in relation to the good.

In 1951, an elderly Jung published Aion, a flawed and difficult book that nevertheless contains insights that remain luminous seventy years after they were written:

“Today humanity, as never before, is split into two apparently irreconcilable halves. The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate. That is to say, when the individual remains undivided and does not become conscious of his inner opposite, the world must perforce act out the conflict and be torn into opposing halves.”

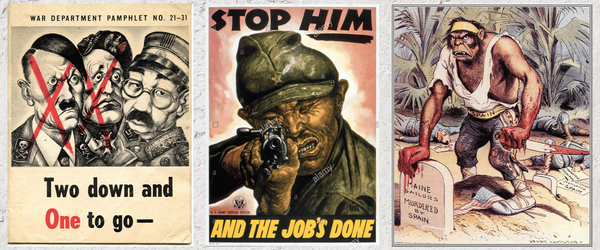

In projecting our psychic double, our impossible shadow, onto others, we both partake in the illusion of moral perfection and justify righteous warfare by any means against others. Jung writes that “most people are content to be self-righteous and prefer mutual vilification (if nothing worse!) to the recognition of their projections”. Thus, we have a world split apart on fundamental empirical and ethical questions, such as the nature of men and women, and the potential justification of abortion and borders, topics on which you are certain to never reach universal consensus.

The lack of mercy within oneself can be projected onto political opponents. In international affairs, it becomes scapegoating – my own country can do no wrong, it is rather the Russians pulling strings, or the threat of nations like North Korea and Iran. The person who denies their shadow, it seems, surrounds themselves with enemies, real or imagined.

Jung writes that a person who denies their shadow will “change the world into a replica of one’s own unknown face.” The evil that you are capable of, denied, becomes the responsibility exclusively of others. Public thinking becomes little more than a command on others to ally themselves with you, as both George W. Bush and radical intersectionality must believe, “You are either with us or against us.”

There are striking overlaps between neoconservative ideology and contemporary social justice. Writer Chris Hedges considers neoconservatism to be a “utopian” belief that force alone can shape the world in the image of the good. Instead, righteous war shaped the Middle East into America’s “unknown face”. The barbarism we believed ourselves to be innocent of manifested in ISIS, our doppelganger, the faceless villain who beheads journalists and rapes women, the darkest possible shadow emerging in the wake of our decisive action. This is not to say that we are equivalent to ISIS, but that our righteous actions reaped moral evils that were even worse than our initial enemy.

Blowback, or the idea that harming others ultimately harms the self, shows up all over American public life. When shame was used as a weapon to defeat ugly ideas and bigotry, the ultimate incarnation of bigotry, Donald Trump, transmuted condemnation into publicity and became the most powerful man in the world. Attempts to isolate him as the opposite of American values failed to prevent him from becoming the international avatar of those values. Shame, likewise, deployed continuously against his supporters since 2016, has failed to cause self-reflection. President Trump’s approval numbers are wholly consistent with an ordinary President’s. America, split into two irreconcilable halves, is unable to distinguish its national identity or deep-rooted problems from the personality of a single volatile man. As such, the whole of politics is reduced to a single personal moral statement: “I find that man deplorable.”

Even as Trump enforces and expands child separation policies that have been in law for years, or exercises inflated military and surveillance powers that were handed down by George W. Bush, and normalized by Barack Obama, there is little impulse for self-reflection. Rather than offering a better alternative to Trump, we idolize the recent past and demonize a man, a cheap trick.

When you attack another person, there is a real sense in which you are attacking an aspect of yourself. The fundamentalist Christian holds many traditional ideas in common with the fundamentalist Muslim – yet, no two people despise each other more. Jung might suppose that we hate those who reveal unpleasant truths about ourselves. In the case of Donald Trump, he has revealed that marketing and politics are the same game – if one can attain unrivaled fame and a social media platform, a person can take over the world. And what, in all honesty, is the intention of our class of social media elites and intellectuals, other than to occupy that identical position of prestige and authority?

The illusion of individual moral perfection, the belief that we alone deserve to sculpt the world in our image, leads to a world of crusaders assembled behind half-truths, whose ideas, egos and personal brands are hopelessly intermixed into the same substance, and each are striving for the loudest voice. But each voice is tethered to the same split heart.

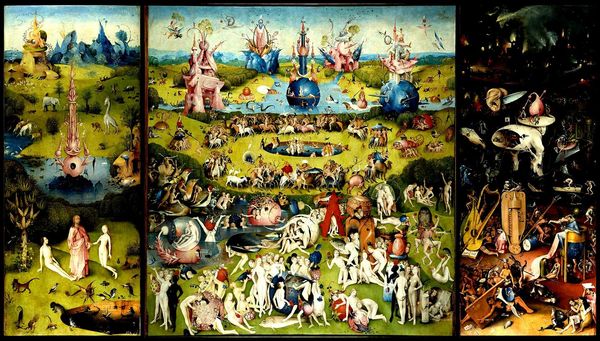

Throughout Aion, Carl Jung uses Christian symbolism as a psychological map of good and evil inside every individual’s heart. Jung argues that Christ, as a symbol of the self, is not divorceable from the shadow of the Antichrist. The existence of Christ necessitates his opposite. Both are referred to as the Morning Star, both are compared to a lion, and in early Christian writings, Satan is the elder brother of Christ. It is not possible to view Christ – and thus the self – as purely good.

Jung conceptualizes the Apocalypse of Saint John, the entire Book of Revelation, as the fevered dream of an imbalanced individual who has conceived only of good his entire life – only to indulge in psychopathic fantasies of the obliteration of a corrupt world run by the Antichrist. The cost of focusing only on good is that the shadow accumulates outside of your vision, in the form of murderous fantasies and hostile dreams.

Our repressed fantasies of domination and destruction shape history. The God of the Old Testament, for Jung, was unconscious of his darker aspects. Yahweh is cruel and unjust in The Bible because he is not conscious of how brutal he is to figures like Job. When mystical ideas border on fascism, it is because they linger in that unconscious domain where good cannot be separated from evil. When we refuse to examine ourselves and integrate our evil into the conscious mind, we risk projecting it into self-righteous fantasies. We make the world into Sodom and Gomorrah.

A culture war is little more than millions of personalities split against themselves, incapable of facing their own shadows, and accordingly hanging the evils of the world on others. Thus, it becomes possible to rant publicly about misogyny while cheating on your own wife or harassing women in your private life. It becomes possible to blame women for your loneliness while basking in what makes you reprehensible, and using the excesses of ideological foes as an excuse to remain complacent and stagnant. The beauty of the shadow is that it spares no one, and even those who face it cannot dissipate it – for Jung, and in all great literary characters, the existence of evil in the self is a brute psychological fact. Integrating the shadow into the conscious self only grants awareness of when one is treading into self-righteous delusion, and consequently, presents the choice of self-control. It never eliminates the shadow and allows one to become perfect.

Manichean dualism is presented in Aion as the opposite philosophy of the Jungian shadow. In Manichaeism, the world is eternally torn between external forces of good and evil. The only moral choice is to align oneself with the good, and moral perfection, and wage zero-sum war against evil.

If one believes that evil is an external phenomenon, and can be destroyed in the bodies of others, then anything is permitted. In its most malicious form, it is the belief that if the people I perceive to be bad no longer exist, then the world will become a utopia.

In fact, the two diametrically opposed sides of contemporary culture match eerily onto the Jungian notions of animus and anima.

The anima is feminine, the source of mercy and grace, the force attempting to upset masculine-dominated history and produce a new world order. The animus, the rational, Apollonian, logical mentality, accused of being male-dominated and phallocentric, defends the pre-existing order and argues to save both the baby and the bathwater. One must tear down the world or ram in one’s heels – no synthesis between these forces is possible. It is as if yin would fight yang for eternity, and the two would never reconcile within the whole of the individual self. Lucifer, the poetic force of freedom against brutal and oppressive Yahweh, in eternal war.

The feminine and the masculine can destroy one another, or cooperate. The self can deny the shadow, or integrate it into a stronger and more honest tomorrow. Striking out against others produces only backlash and doubling-down upon the hatches, and even rational argument, clearly, has never converted opposing armies to one’s preferring side.

We have all built up armies within ourselves to guard our paradoxical secrets from discovery. What would happen if many of us resolved to approach those secrets with open hands?