Steve Taylor • • 7 min read

Original Influences: How the Ideals of America Were Shaped by Native Americans

In the summer of 1938, the young psychologist Abraham Maslow spent several weeks doing anthropological research on a Blackfoot reservation near Alberta, Canada. His experiences on the reservation had a powerful impact on him, and completely overturned his socially conditioned views of Indians. He was struck by the generosity and egalitarianism of the Indians, as well as their fundamental decency and respect for others.

As Maslow’s biographer Edward Hoffman writes, Maslow discovered that “to most Blackfoot members, wealth was not important in terms of accumulating property and possessions: giving it away was what brought one the true status of prestige and security in the tribe.” At the same time, Maslow was shocked by the meanness and racism of the European-Americans who lived nearby. As he wrote, “The more I got to know the whites in the village, who were the worst bunch of creeps and bastards I’d ever run across in my life, the more it got paradoxical.”

This experience influenced Maslow’s “humanistic” psychology, which conceived of an innate positivity in human beings and pointed towards a more benevolent form of society. Maslow was also struck by the empathic connection he himself felt with the Blackfoot and his sense that as individuals they were essentially (despite their cultural differences) no different to any other Americans he knew. This inspired him to think in terms of a new kind of psychology that dealt with fundamental aspects of human nature. Almost as soon as Maslow returned home to Brooklyn after his summer with the Blackfoot, he was, as Hoffman writes, “already conceptualizing a new biologically rooted but humanistic approach to personality transcending the narrowness of cultural relativism.” (1)

There is even the possibility—put forward by some indigenous academics such as Professor Cindy Blackstock and Leroy Little Bear—that Maslow’s exposure to Blackfoot culture was instrumental in his formation of the “hierarchy of needs” model, which he first presented in 1943. The Blackfoot conceive of reality in the form of a tipi, made up of different levels that converge into each other, so it is easy to see the similarity with Maslow’s model.

This story suggests that Native American culture may be more influential in the history of psychology than is generally realized. But the story also relates to a much wider issue, which I’m going to explore in this article: how much American culture, in general, has been influenced by the ideas and principles of Native American groups, and how little this influence has been acknowledged. As I discuss in my book The Fall, this was particularly the case with the American ideals of democracy, equality, and individualism.

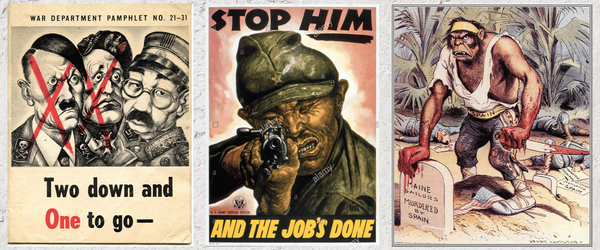

The Editing of History

I grew up in the U.K., and studied history at school up to the age of 18. We covered a lot of different countries (mainly in Europe), but there was one country which we didn’t touch on at all: Ireland. When I visited Ireland as an adult and did some reading about the country’s history, I was shocked to find out about episodes like Oliver Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland, the potato famines, and Bloody Sunday. All of that seemed to have been edited out of the official history of England. As the saying goes, history is written by the winners, who can choose to edit out anything they choose. And to some extent, this appears to have happened in American history. The Native American influence has been largely edited out.

For example, many people believe that the concept of democracy comes from ancient Greece. But aside from the fact that the Greeks had a very “special” idea of democracy—including slavery and the oppression of women—there’s a much stronger case for the view that Western democracy comes from Native American groups. The American constitution’s concept of a non-hierarchical society in which everybody had equal rights—which was, after all, completely alien to Europe at that time—was to a large extent inspired by Native American societies.

Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin both wrote in their memoirs that they were influenced by the Iroquois model of democratic government, with its system of checks and balances and elected representatives (2). Similarly, the idea of a union of different states was adapted from the Native Nations League of the Iroquois. In fact, the idea was actually recommended to the Europeans by a leader of the Six Nations at a treaty signing in 1744, at which Benjamin Franklin was present. (3) The League of Iroquois had its own carefully worked out constitution and laws, which leaders learned by heart and passed on orally from generation to generation, which the founding fathers borrowed from.

(Ironically, as well as being the originators of modern capitalist democracy, the Iroquois were also partly responsible for the creation of Communist states. In 1851, Lewis Henry Morgan’s book League of the Iroquois was published. Both Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels read the book and were also inspired by what they saw as an example of a Utopian socialist society. As Engels wrote to Marx, “This gentle constitution is wonderful! There can be no poor and needy…All are free and equal—including the women.”[4])

Egalitarianism

Whether they lived as hunter-gatherers or had a settled lifestyle, the great majority of Native American societies were strikingly egalitarian. Early European colonists were often shocked by this since it was so different from what they were familiar with at home. As one British officer wrote disapprovingly of the Cherokee Indians in the eighteenth century, “There is no law nor subjection amongst them…The very lowest of them thinks himself as great and as high as any of the rest…Everyone is his own master.”(5). Land and property were usually communally held and used. There were generally no strongmen authoritarian rulers who impose their desires on the rest of the population against their will. Instead, there was an even distribution of power, with all individuals participating in decision making. As the historian Alvin Josephy wrote of the Hopi Indians, for example, “In none of the towns were there social classes or differences in wealth; everyone, even members of the theocracies, worked and shared as equals.”(6)

At the same time as emphasizing egalitarianism, Native American societies were also extremely conscious of what we would call the “rights of the individual.” As Colin Taylor writes, one of the central principles of the Iroquois and the Algonquian Indians “emphasized and defined the rights of the individual such that all actions of individuals were based on their own decisions and all group actions on the consensus of the participants.” (7)

The combination of egalitarianism and individualism is one of the defining characteristics of American society, as envisaged by the founding fathers. And it is highly likely that their vision of America was greatly influenced by their observations of and encounters with Native Americans.

Generosity

The generosity that Maslow encountered amongst the Blackfoot Indians was by no means unusual. In most Native American groups, generosity was a moral imperative, and any expression of greed or selfishness was seen as a crime. Indian chiefs were often expected to work as “social security”organizers, and to provide for the sick and needy from their own resources, or else to arrange contributions from others. Because of this, chiefs were usually no more wealthy than anybody else—and even expected to be poorer. The Assiniboin Indians, for example, judged how able their chiefs were by their generosity, and any who displayed meanness were likely to be deposed. (8)

Benjamin Franklin made some illuminating comments on the customs of generosity and hospitality of Native Americans. In a piece called ‘Remarks concerning the Savages of North America’ written in 1782, Franklin wrote admiringly of the way that Indian villages would have a ‘stranger’s house’ that travellers were welcome to stay, and how they would offer food and services to strangers without charge. He quoted one Indian’s dismay at the white man’s uncivility:

“You know our Practice. If a white Man in traveling thro’our Country, enters one of our Cabins, we all treat him as I treat you; we dry him if he is wet, we warm him if he is cold, we give him Meat & Drinks that he may allay his Thirst and Hunger, and spread soft Furs for him to rest & sleep on: We demand nothing in return. But if I go into a white Man’s House at Albany, and ask for Victuals & Drink, they say, where is your Money? and if I have none; they say, Get out you Indian Dog.” (9)

Sexual Equality

As the anthropologist M.A. Jaimes Guerrero pointed out, when the founding fathers adopted the Native American principles of democracy, the one important aspect they missed out was the authority and leadership of the clan mothers (10). In fact, the great majority of Native American societies appear to have been non-patriarchal. Matrilinear and matrilocal societies were common, and women often had a large degree of authority. In fact, in many cases, they had more control over political matters than men. Women often had the job of nominating new chiefs, and when agreements were made between Native Americans and Europeans documents often had to be signed by women, since the marks of men didn’t carry any authority. Women were not seen as inferior to men, and as a result were not dominated or abused. As the anthropologist Elman Service wrote of the Yahgan of Tierra del Fuego, for example: “Women enjoy particularly high status…In their wider social relationships, women are not expected to keep quiet or to be more demure than men.” (11) The Copper Eskimos of northern Canada accept the equal status of women to such an extent that men’s and women’s roles are interchangeable so that men sometimes do women’s work and vice-versa. (12) And in contrast to many male-dominated societies—where men were often entitled to throw out their wives and leave them to starve if they so desired, while women had no divorce rights at all—Native American women were usually free to end their marriages at any time. A woman of the Pueblo culture, for example, could divorce her husband simply by placing his possessions outside her door, at which point he would return to his mother.

All of this makes it clear that Native American groups were culturally much more advanced than history generally credits them. In fact, with regard to women’s rights (and generosity!), we arguably still haven’t caught up with them. It is also clear that modern America would not exist without the influence of Native Americans. Their massive influence should be gratefully acknowledged, rather than edited it of history.

References

(1) Hoffman. E. (1996). ‘Abraham Maslow: A Biographical Sketch.’ In ‘Future Visions: The Unpublished Papers of Abraham Maslow.’ London: Sage.

(2) Wright, R. (1992). Stolen Continents. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

(3) ibid.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Josephy Jr., A.M. (1975). The Indian Heritage of America. London: Pelican.

(7) Taylor, C.F. (Ed.) (1991). The Native Americans. London: Salamander Books.

(8) Ibid.

(9) http://www.wampumchronicles.com/benfranklin.html

(10) Jaimes Guerrero, M.A. (2000). “Native Womanism: Exemplars of Indigenism in Sacred Traditions of Kinship.”In Graham Harvey (Ed.), Indigenous Religions. London and New York: Cassell.

(11) Service, E.R. (1978). Profiles in Ethnology. New York: Harper and Row.

(12) Ibid.