Jon Brooks • • 6 min read

Enlightenment: Seek and You Shall NOT Find

A Zen student goes to a temple and asks how long it will take him to gain enlightenment.

“10 years,” says the Zen master.

“Well how about if I work really hard and double my effort?” the student asks.

“20 years,” comes the reply.

This story beautifully points out the paradox of the spiritual path:

The more we chase enlightenment, the more it eludes us.

Or in more technical terms:

Craving is intrinsically linked to suffering, and one must practice overcoming craving without craving to overcome craving to attain the cessation of suffering.

Forced Enlightenment

Spirituality means different things to different people, but common among all forms of spirituality is the aim of weakening one’s attachment and unhealthy desires.

The Buddha said everything he taught could be reduced down into a single sentence:

“Attach nothing to me or mine.”

Many of the greatest sages throughout history have echoed this statement.

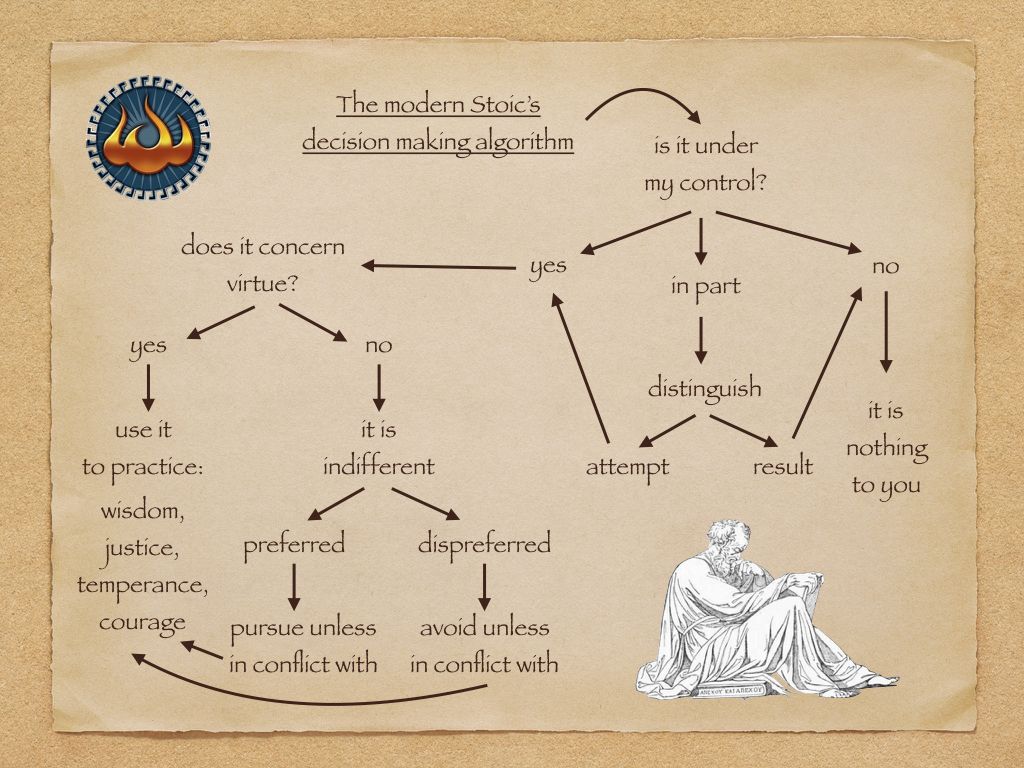

The Stoics, agreed with much of the Buddhist ideas on craving. Epictetus cut straight to the heart of the issue when he said:

“It is impossible that happiness, and yearning for what is not present, should ever be united.”

It is only when we are attached, or when we crave something that we can feel disappointed when things don’t go as we’d like.

To try and force enlightenment is to live a contradiction. If one craves not to crave then one will never be free from craving.

This is akin to an ascetic who is willing to let go of everything other than their own asceticism.

The ego is the ultimate trickster, and when you employ it to self-destruct, expect nothing but the illusion of progress.

When I spoke to Jules Evans for the HEx podcast he also explained how psychedelics—a popular ego-dissolution tool—can be used to inflate one’s ego if one is not careful:

“You may be having the most extraordinary psychedelic experiences. You may be communicating with DMT-entities. Mamma Ayahuasca might be visiting you nightly. But if it’s not making you a kinder person, then it’s just a holiday. It’s just a thrill. You might as well just be watching a movie. You might as well be watching Disney’s Fantasia because it’s not making you kinder person. It’s not making you a more loving person. It might even be making you a worse person because you’re becoming a self-regarding, vain dick.

— Jules Evans

Psychological Consumerism

“When a movement arises to oppose a current culture, it often inherits the telltale structure of its predecessor.”

— Derren Brown, Happy: Why More or Less Everything Is Absolutely Fine

The ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus classified things into “essential needs” and “inessential needs.” He argued that everything that we actually need—all that is essential—is quite easy to procure.

It is the things that we desire but don’t need that causes us trouble, namely because these things are inexhaustible.

Psychologists call this concept hedonic adaptation. When we acquire a new smartphone, for example, it doesn’t take long before the excited, mesmerized look we have while gazing at it is replaced by the expression of boredom.

We are capable of adapting to anything.

Marketers know this and are extremely good at releasing “updates” to their products which makes the previous versions, which you once loved, seem like obsolete pieces of junk.

I believe that this same kind of hedonic adaptation can happen purely in the realm of the mind.

Some people who are anti-materialism and anti-consumerism inherit the exact structure of the thing they’re against, but instead of searching for new shoes to fill the hole in their self-esteem they search for new documentaries or “insights” to make them feel more whole.

There is nothing inherently wrong about seeking out knowledge that fills you with excitement, but there is a danger when it comes to learning about spirituality or self-improvement.

The danger is that we may always be living in the future, chasing the next piece of the puzzle, never feeling good enough, mastering no fundamental principles, and living with the delusion that “old” knowledge is junk compared to the new things we’re learning.

If one seeks enlightenment with too much effort, one may get stuck in a cycle of craving new “enlightening information” which blocks one from a liberated life in the here and now free from suffering.

Accidental Enlightenment

The Buddha himself tried in vain to force enlightenment for over 6 years.

During this time he gave up all of his material possessions, fasted to the point of nearly dying, and lived among the dead.

All of this, and no enlightenment.

It was only after the Buddha relaxed his diet and stopped his extreme asceticism that he had his awakening under the Bodhi tree.

When the Buddha stopped craving enlightenment so much, he attained it.

The spiritual teacher Eckart Tolle also attained his enlightenment “by accident” the day after he seriously contemplated ending his life.

This is not unusual.

Transpersonal psychologist Steve Taylor, PhD., has conducted research on “awakening experiences” and found that extreme emotional turmoil was the biggest catalyst for enlightenment.

Alan Watts in The Way of Zen lists some other examples of Zen practitioners achieving accidental enlightenment through the following means:

- Hearing the caw of a crow

- Listening to the sound of softly falling of snow

- Cleaning up after breakfast

- Being knocked out unconscious

- Getting struck by lightening

What do all of these activities have in common? Very little, other than they are all places you would not seek enlightenment from.

How to Accidentally Become Enlightened

By this point, it is worth considering if enlightenment is even a worthwhile goal.

In some sense enlightenment is The Ultimate Goal.

Few would argue that our consciousness is the most precious thing we have.

And in some sense, the quality of our mind will in large part determine how often those closest to us will experience joy or suffering.

What would be better than to “perfect it”—that is to make it free from suffering and delusion, fully attentive, and overflowing with compassion?

The problem, as we’ve seen, is that we chasing after enlightenment is a lot like chasing after a rainbow.

So how do we solve the spiritual paradox, to repeat:

Craving is the seed of suffering. Therefore, if we crave the end our suffering we only prolong it.

Cicero hints at an answer with the following analogy:

“If a man were to make it his purpose to take a true aim with a spear or arrow at some mark, his ultimate end, corresponding to the ultimate good as we pronounce it, would be to do all he could to aim straight: the man in this illustration would have to do everything to aim straight, yet, although he did everything to attain his purpose, his ‘ultimate End,’ so to speak, would be what corresponded to what we call the Chief Good in the conduct of life, whereas the actual hitting of the mark would be in our phrase ‘to be chosen’ but not ‘to be desired.’”

Cicero was a truly great mind and well versed in Stoic philosophy. He is saying here that the wise archer would see aiming straight as his ultimate goal, and the hitting of the target, as he beautifully puts it, would “be chosen but not to be desired.”

Desire here is not linked to the healthy desire we have towards our partner or pleasurable food when we are hungry. Desire here is linked to the craving for the external world to match our wishes.

The idea here can be translated for our purposes as:

Aim for the greatest good but measure your progress only according to the things within your control.

And what is in your control?

Your intentions and actions.

Everything else, including mind states like enlightenment, is not within your complete control.

The game of enlightenment is not one you can guarantee you’ll win, and for as long as you chase after a goal that is susceptible to the changing temperament of fortune, you are seeking wisdom through unwise means.

A better approach is to focus only on the daily actions and habits within your control that you believe will increase the chances of attaining accidental enlightenment, all the while being completely content with that never happening.

You must give up any craving you have for external spiritual progress. All results come secondary to one’s intentions.

Enlightenment is extremely difficult to attain exactly because we view it as something difficult to attain.

The person who stops searching for enlightenment as something external or graspable altogether and instead only focuses on acting as an enlightened person might act to the best of their abilities is already being as enlightened as they will ever be, since this is exactly what an enlightened person does anyway.

It’s also worth questioning our fundamental assumptions about enlightenment. Many of us discuss if it’s possible or not and what it feels like, but let’s take a step back.

What if enlightenment is something that you can’t ever actually get?

What if enlightenment can never be found because the act of searching for it only makes it move further away?

What if enlightenment is only something you can give—a quality you can give to the world, to the people around you, to yourself?

How long do you want it to take for your enlightenment to happen?

Jon Brooks

Jon Brooks is a Stoicism teacher and, crucially, practitioner. His Stoic meditations have accumulated thousands of listens, and he has created his own Stoic training program for modern-day Stoics.