Martijn Schirp • • 3 min read

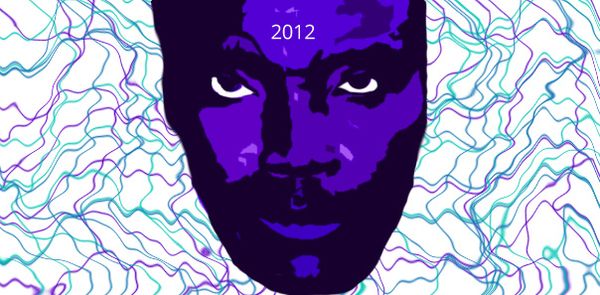

A Quick Note On Kony 2012 And Confirmation Bias

“It is a habit of mankind … to use sovereign reason to thrust aside what they do not fancy.” – Thucydides 431 BCE

Who would have thought that a video portraying the war crimes of a self-proclaimed messiah in Uganda would cause the biggest splash in social media as of yet? The emotional message made by the organization Invisible Children has spread like wildfire and has gained 16.7 million views on Vimeo and 76 million on YouTube, in just a little over a week time. When the suffering of the abducted children entered my home, my first reaction was void of any skepticism. I was ready to join their cause.

But like always, various critics raised their voices, questioning the means and goals of the organization behind the Kony 2012 movement. From spending more money on making videos than on helping children, to being funded by JP Morgan or hiding their true motive: to get a foothold in Uganda for American oil interests. Whether or not Kony 2012 is a good thing or whether or not it might be seen as a prototype for a new type of social movement remains in the dark, yet it points to a phenomenon that is very important.

More often than not we selectively pick information that already supports the view we have. We never take the time take in the viewpoint of the opposite side, we automatically assume the evidence we gathered is sufficient to support our conclusions. But this is a false assumption, one which can be quite dangerous.

For example. John sees a dozen white swans and then hypothesize that all swans are white. To test his hypothesis, he starts looking for more and more white swans, and after finding another couple dozen he indeed concludes that all swans are white. But this is a wrong approach. What John should have done is looking for swans that are not white. Because once he finds one, he knows his hypothesis is false, while no amount of white swans can ever tell him he is right. In fact, only focusing on validating a hypothesis might blind one from actually seeing or weighing in any counter evidence.

This is called the confirmation bias and everyone has it. Another clear example can be found in almost anyone’s first reaction to the Kony video. We assume the organization has good intentions and we assume that their means of fighting Kony are the right ones. But actually we don’t know, because we haven’t tried to find the black swan yet. And so we don’t know if there are better organizations to capture Kony or that there might even be better causes.

To be aware of this bias in ones own life we place an information filter around our brains. Once we start looking for arguments that refute our own we start having a force that eliminates the bad ideas so the only good ones remain. Falsifying arguments lies at the heart of the scientific method. It works like evolution: good and truthful ideas only get a chance when the bad and wrong ones die out.

The goal is not to join the movement or to give money to Invisible Children. The goal is to get war criminals in court and to help Africa become independent. To reach this goal, supporting the Kony movement might be the best way to go. But it also might be the worst one. This is why we need to let go of our confirmation bias and try to falsify their means. Is sharing a video on Facebook the best way to stop Kony? Or is it a way to get away with feeling good by supporting the cause? Do the Ugandan people really need our help or is it an excuse to invade a country with hidden motives? There is only one way to find out, and that is to learn about both sides of the argument. That of Invisible Children and that of its critics, the Ugandans, news reporter and other organizations. And once you found the right means, and only then, get into action.