Connor Hensel • • 14 min read

Digital Journalism: Post-Truth and The Crisis of Objectivity

“For many years I used to end my day at the Donut Mill where we would smoke cigarettes, drink coffee and discuss the issues of the day. Often we were not in agreement and that was just fine. That is no longer the case. Today we have gone to our ideological corners and quickly paint our opponents as xenophobes, snowflakes etc. The civility is gone. No longer can you have an honest discussion without being castigated. This is dangerous.” (Cain)

For many of us, in recent years it has felt like the ability to have a healthy debate has been all but lost. In 2018, UK minister of state Sam Gyimah warned that “debate among students is being stifled because white people are not allowed to talk about race,” and that people are finding themselves unable to voice views on transgender issues “unless they are trans themselves.” He stressed that these are symptoms of a student monoculture which assigns people an ‘identity’ and tells them they cannot comment on anything else.

Hearing statements like Gyimah’s, one can’t help but wonder: what is causing this erosion of civility and discussion? What are the implications of people being stifled, censored and convinced their opinions are not valid because of their identity? What is it about today’s society that leaves us residing in our so-called ‘ideological corners’?

What is the Purpose of Journalism?

The American Press Institutes guide to the basic principles of journalism states that the foremost value of news is as a utility to empower the informed:

“The purpose of journalism is to provide citizens with the information they need to make the best possible decisions about their lives, their communities, their societies, and their governments.” In The New York Times ‘Ethical Journalism’ handbook of values of practices, the organization recognizes the importance of respect for the readers and commitment to truth: “The Times treats its readers as fairly and openly as possible. In print and online, we tell our readers the complete, unvarnished truth as best we can learn it” (‘Ethical Journalism,“ 2018).

Journalism, one could say, is about respectfully providing the whole truth to citizens so they can make informed decisions. Despite these strong values and commitments at its core, journalism is always changing and evolving, and has experienced several revolutions in past decades.

Journalism specialists Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel covered such revolutions in their 2001 book, The Elements of Journalism. They tell the story of how 25 journalists and academics came to be sitting around a table at the Harvard University Faculty Club in 1997 with the notion that something was seriously wrong. They were concerned about journalists consumed with business pressure and the bottom line, realizing that “they didn’t recognise some of what passed for journalism in the media. Journalism wasn’t serving the public, and the public increasingly distrusted, even hated, journalists” (McGuire).

You might assume things have improved since then, but in fact things have only gotten worse. In 2016, nearly 20 years later, a survey conducted by CBS and Vanity Fair magazine found that Americans now saw the mainstream media as the most unethical business, even more so than pharmaceutical companies and the banking industry (Dice 20).

Columbia University professor James Carey, who was part of the discussion, suggested that “the problem is that you see journalism disappearing inside the larger world of communication. What you yearn to do is recover journalism from that larger world” (McGuire).

Understanding Objectivity

Media scholar Michael Schudson found that the commercialisation or ‘selling out’ of journalism observed by Kovach and Rosenstiel goes hand in hand with the evolution of the principle of objectivity. In his 1978 book Discovering The News, Schudson uncovers when, where and why the ‘objectivity principle’ came into use by commercial media organisations, eventually becoming an assumed characteristic of what is to this day often called “quality” or “serious” journalism.

Use of the term ‘objectivity’ by a journalist was intended to signify his or her maintenance of neutrality or ideological detachment. In other words, objectivity is a term that can be appropriated and employed by news organizations and journalists, consciously or unconsciously, to secure the consent of the reader to consider the text as knowledge, and thus maximise the chances of its reception as a truthful account of reality.

The overt application of the principles of objectivity by the journalist framed the content to which it was attached in such a way that it was less likely to be challenged or questioned, more likely to be believed. (McNair)

The performance of objectivity is said to minimise public contestation of “the news” by making invisible the values and choices that guide the selection, creation and distribution of news stories.

Serving such a function makes this practice of objectivity useful to those with an interest in influencing public opinion, which makes one question the motives or intent behind the initial institution of the concept, Schudson observed, though, that “objectivity had emerged… without planning or conscious direction by some conspiracy of the capitalist elite, but as an adaptive response to economic, political and cultural trends in the surrounding environment” (McNair).

Essentially, as Western society transitioned from feudal European class systems into its modern capitalist form, journalism shifted from an instrument of partisan propaganda to a source of factual information, and this paved the way for adoption and application of the objectivity principle.

More recently, with the rise of postmodern ideas surrounding the notion of factuality and the nature of reality, a culture emerged where objectivity was seen as flawed, if not necessarily bad, or wrong:

Objectivity was recast in the light of a widespread belief in the impossibility of absolute truth, the importance of observer perspective, and the mediating role of subjectivity in the interpretive work done by both journalists and their consumers as they processed the “facts” of a given situation. (McNair)

This recasting of objectivity inspired journalists at news organizations such as the BBC to update their practices, and make explicit some of the choices made in the production of a story. It became acknowledged that truth was not something easily recovered from a given set of facts, and could never be definitively isolated from the plurality of available interpretations.

Despite this notable evolution, the overt displays of bad faith and wilful deceit seen in the work of some journalists, employed by so many highly regarded journalistic outlets, brought on a true “crisis of objectivity” in the late 1990s and into the 2000s. Claas Relotius comes to mind, a reporter and editor who was fired from his job at top European news outlet Der Spiegel for fabricating at least 14 news stories. Relotius had received two awards from CNN International in 2014, which he would later be stripped of when his falsified stories came to light (Pham).

Opinion polls in the 2000s showed that faith in journalism’s accuracy was falling in the UK and the US. Sales of newspapers and broadcast ratings slumped in the wake of the internet as a new medium for news delivery, which occurred alongside increasing general public dissatisfaction with the product news outlets were offering. Ensuing commercial pressures encouraged erosion of the fact/commentary distinction, and led to a vicious circle of decline and erosion.

The Post-Truth Era

Public service media survive, as does support for the notion of objectivity in journalism, but even before the unprecedented rise of what has been called “post-factuality” or “post-truth” culture in the era of fake news, they were being challenged as never before in the history of liberal democratic news culture. (McNair)

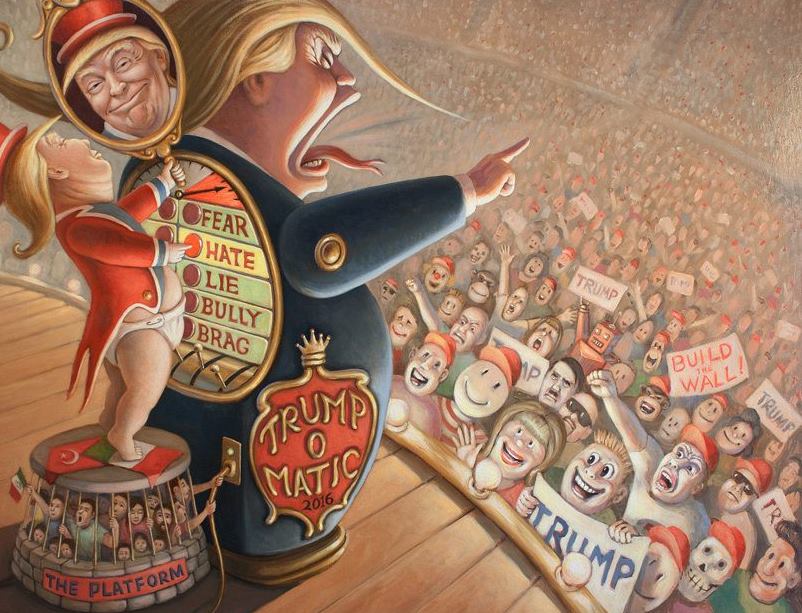

The Oxford Dictionary declared “post-truth” as the word of the year in 2016 after it’s usage increased roughly 2000 per cent in the wake of the media debacles surrounding the “Brexit” referendum and Donald Trump’s political campaign.

Defined in the dictionary as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”, post-truth aptly describes the conditions of a cultural climate characterized by information overload, light-speed communication, and distrust of “official” sources and mainstream media.

Post-truth does not mean that an era of widespread lying has replaced one where truth triumphed; rather it is about “blurred bearings and establishing an indifference to truth.” One of the biggest challenges for journalists in the US has been how to report objectively the conduct and policies of a Trump administration which appeared simply not to care about the known facts of a given issue or situation, and preferred to define its own truth according to its short-term needs.

Trump’s adviser Kellyanne Conway provided a memorable example of post-truth in January 2017, when she excused exaggeration of the numbers attending Trump’s inauguration as “alternative facts.” While it’s true that the corroboration and verification of facts upon which journalism relies remains valid, the question that remains is ‘what do news media do when the so-called “primary definers” of complex reality, such as the president, base their policy statements on false or unreliable information?’

Well, some news outlets are choosing to defy long-held conventions of journalistic practice. In 2017, Buzzfeed published a 35-page dossier on Donald Trump’s relations with Russia, alleging his participation in fetishistic sexual practices, conspiracy with Russian security services to target Hillary Clinton and other potentially damaging transgressions.

After Trump and his supporters dismissed the document as “fake news” because it was anonymously sourced and thus unverified, Buzzfeed declared that the American people should judge its contents for themselves. No news outlet published the dossier, not because it was fake, necessarily, but because it had not been objectively processed by journalistic professionals:

”…only BuzzFeed, a relative newcomer amongst the mainstream US media with an incentive to get its brand publicised, decided that the unprecedented circumstances of the Trump presidency justified a violation of this basic ethical principle.” (McNair)

Many believe the dossier was just part of a disinformation campaign designed to smear Donald Trump, and Buzzfeed would later be sued for defamation for publishing the story (Dice 6).

Populism & Anti-Intellectualism

In their essay Populism, Journalism, and the Limits of Reflexivity: The case of Donald J. Trump, journalism and communications specialists Michael McDevitt and Patrick Ferrucci make the case for a subsistent ‘anti-intellectualism’ or ‘anti-elitism’ that structures observable content. McDevitt and Ferrucci work from a modified version of Douglas Hofstadter’s definition of anti-intellectualism, described as follows:

The common strain that binds together the attitudes and ideas which I call anti-intellectual is a resentment and a suspicion of the life of the mind and of those who are considered to represent it; and a disposition constantly to minimize the value of that life. (McDevitt and Ferrucci 513)

Commercialisation of media, emergence of postmodern ideas, digital technology, erosion of objectivity, and declining integrity of journalistic outlets have all contributed to the inflation of anti-elitist sentiment, i.e. mistrust of an upper social class viewed as haughty and highbrow. Examples of anti-intellectualism though are difficult to identify, as it entails opportunities not taken, context not provided, and ideas otherwise not engaged, so despite its apparent influence it is rarely recognized or subject to measurement.

One potential consequence noted by McDevitt and Ferrucci is increasing public support for more severe criminal justice policies regardless of their ability to reduce crime, otherwise known as ‘punitive populism’, pointing out that punitive populism encompasses elements of anti-rationalism and anti-elitism.

“Populism considers society “to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’”… Journalism’s indulgence in the imaginary of the volonté générale (general will) is consequently both defensive and opportunistic as the news sustains a mesmerizing message in the countdown to Election Day.” (McDevitt and Ferrucci 514)

The Imagined Audience

While news journalism is a product of the minds of those who create it, its production and presentation are heavily influenced by the audiences that journalists perceive or imagine. Communications professor and former journalist Barbie Zelizer traces back the notion of an imagined audience to the late 1940’s, as enmity between the United States and the UK was being replaced with the notion of an Anglo-American ‘Special Relationship’ that was expected to meld the best of new and old worlds.

Extensive scholarship tracks how this imaginary played out in news. Work by Lee (1976), Tunstall (1977), Schudson (1978), Chalaby (1998) and Deuze (2002) chronicles the emergence of news across the 19th and 20th centuries as primarily an Anglo-American invention, one that saw itself as a model for journalism everywhere. Patching two separate claims to exceptionalism into one curious alliance, this imaginary circumvented all kinds of incongruities (Zelizer 142)

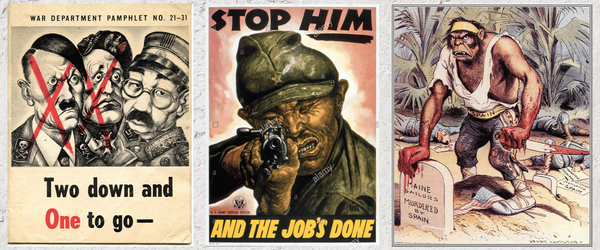

Originally, the notion of the public remained high-minded, and journalists expected to engage with a reasoned, articulate, and mostly stable public invested in public events, able to discern and eager to understand. As American power consolidated and strengthened following WWII, American journalists accommodated a growing insider status, often acting as spokespeople for US policy and talking to the public rather than listening to what the public had to say to them. Such changing roles and a growing disconnect between the media and the public fueled a shift in journalists perception of their audience from high-minded to a public disinterested, censored, silenced and repudiated. As journalism came to view itself as tribune of the people, populist anti-elitism was rationalized (so to speak) as journalists imagined an agitated public.

Such indulgence in the imaginary had journalists feeding and reflecting this situation of public vs. elite, and operating on the notion that problematic practice is not so much justified to the public as the public is imagined in ways that justify problematic practice. Looking at the way media coverage unfolded over the duration of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign helps to illustrate the effect of this:

In 2016, the eventual Republican nominee for president received “free” and mostly favorable coverage from Fox News but also institutions in the elite press, including The New York Times and The Washington Post (Patterson 2016). Neither Trump’s poll numbers nor fundraising ability explains the level of attention. “Journalists seemed unmindful that they and not the electorate were Trump’s first audience”. With no credentials and no constituency, Trump understood instinctively that respectable media would cooperate. (McNair 514)

The problem with anticipation of a punitive public is the way such a mindset can influence the management of public attention, and the amount of coverage that Trump received from the media can be seen as a symptom of this anti-elitist imaginary in journalism. The coordination of public attention is a powerful resource in the diffusive and networked media environment we live in, and daily headlines with relentless criticism of Trump ultimately did more to help his popularity than hurt it.

Similar to the case of Trump in the US, journalism in the UK has been heavily criticized for failing to reflect the public, described in this account of the “Brexit” referendum:

Print media coverage… displayed multiple shortcomings: not providing enough hard information, not constructing enough thoughtful context, not sparking public trust, peddling too many false alarms. Falling short on the mandate to inform, print journalism offered little more than what Cushion and Lewis (2017) characterized as a ‘statistical tit for tat between rival camps’. This inability to accommodate complex reasoning helped orient coverage to a gaming or horse race narrative (Levy et al., 2016). Although here too exceptions existed, such as The Guardian or Channel 4 News, the coverage of Brexit, in many ways like that of Trump, underscored colossal changes in institutional culture that should have promoted adjustments on the adjacent news landscape. The implications, then, of focusing on method and failing to ask what journalism is for were enormous. (Zelizer 149)

The Cold War Redux

It thereby stands to reason that the Anglo-American imaginary has not necessarily produced journalism in line with its assumptions. Yet it remains. Although its workability has been repeatedly challenged – coverage of the so-called War on Terror is one example – an earlier challenge that unfolded during the late 1940s and early 1950s offers a clear historical parallel to the circumstances of today. That parallel is rooted in the Cold War. (Zelizer 143)

As Mark Twain once said, “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” a quote which may come to mind while considering the cold war media environment that was remarkably similar to todays. The 1950’s are described as a time of conformity, homogeneity and restraint, where fear and doubt were everywhere. “It was a time in which individuals showed caution when taking risks or causing offence,” Zelizer writes, pointing out that journalism was “not immune to such impulses” (144). Journalists and others were subjected to increasingly punitive measures in a witch hunt for communists, which is reminiscent of events happening today as our society experiences what some refer to as a ‘manufactured political correctness crisis.’

A similar mind-set has continued unabated more or less since the Cold War, and it affects both journalists and their audiences:

Journalists acted like exterminators going after the wrong insects, trying to get rid of any evidence of their own perspective, bias or opinion so as to do what they claimed was their job. This would have disastrous effect…. And most important, that critical question of what journalism is for received no attention at all. Instead, journalists sidelined the meanings of the events being covered and failed to give the public what it needed to know – when people still cared and it still might have made a difference. (Zelizer 145)

The Way Forward

Between 1945 and 1979, the overt partisanship that was characteristic of print journalism became more muted, however, it would prevail alongside multiple kinds of power attachments — to government and the market — that complicated claims to neutrality. Commodification, power attachments and partisanship are unavoidable realities in the current world of news journalism, but extreme anti-intellectualism and post-truth conditions are problems that can and must be remedied if the media is to honor its mandate to educate and inform.

French psychologist Revault d’Allonnes concluded that “in the long term, education, public debate and the arrival of new generations offer the greatest hope of emerging from the trap of post-truth” (Marlowe). As the worldwide transition into digital media continues, media theorists are looking at how the concept of objectivity can be refreshed for a digital era. When we are unbalanced and overly driven by emotion it can be easy to forget that the capacity to be objective, and to perform the functions of critical scrutiny of power, is not a function of ideological affiliation.

Willingness to question authority, acknowledgement of the imaginary, and transparency of methods and affiliations will be key in a shift towards true objectivity:

Objectivity will continue to be a key pathway to the mobilisation of trust in journalism, but in the post-factual world where powerful sources brazenly assert the Truth of their demonstrably untruthful versions of events, objectivity must include a determination to challenge “authoritative” sources as never before… At the same time, journalists claiming objectivity must make even more visible and transparent the limitations inherent in their own processes of truth and meaning-making. (McNair)

There is optimism for the future of objectivity in journalism. Journalists are increasingly willing to criticize their work in digital media, signifying a shift to greater transparency. Increasing professional reflexivity is an important part of the way forward, described as “journalists capacity for self-awareness; their ability to recognize influences and changes in their environment, alter the course of their actions, and renegotiate their professional self-images as a result” (Ahva 791).

If the concept of objectivity in journalism arose and was established in the nineteenth century’s growing demand for authoritative, reliable information in an increasingly complex, globalised world, that logic applies even more to a digital media environment of millions of providers and billions of users. The traditional sense-making role of journalism in relation to complex reality can be argued to increase in social importance as reality grows still more complex and difficult for the individual to navigate in the twenty first century. (McNair)

Works Cited

- Adams, Brian. “History Doesn’t Repeat, But It Often Rhymes.” HuffPost Australia, 18 Jan. 2017, www.huffingtonpost.com.au/brian-adams/history-doesnt-repeat-but-it-often-rhymes_a_21657884/.

- Ahva, Laura. “Public Journalism and Professional Reflexivity.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, vol. 14, no. 6, 2012, pp. 790–806., doi:10.1177/1464884912455895.

- Cain, Bruce. “The Enlightenment Is Dead. Welcome to the ‘New Age’ of Globalist Anti-Intellectualism.” Facebook, 19 Mar. 2019, www.facebook.com/notes/bruce-cain/the-enlightenment-is-dead-welcome-to-the-new-age-of-globalist-anti-intellectuali/3051128898246411/?fref=mentions.

- Dice, Mark. The True Story of Fake News: How Mainstream Media Manipulates Millions. The Resistance Manifesto, 2017.

- Harding, Eleanor. “White Students ‘Feel Unable to Talk about Race and It’s Stifling Debate’.” Daily Mail Online, Associated Newspapers, 6 Nov. 2018, www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6360995/White-students-feel-unable-talk-race-stifling-debate.html.

- Marlowe, Lara. “A Philosopher’s Take on the Dangers of Our Post-Truth World.” The Irish Times, The Irish Times, 9 Apr. 2019, www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/a-philosopher-s-take-on-the-dangers-of-our-post-truth-world-1.3853554?fbclid=IwAR1s9SKjHiZ8ytn4Pt-FTqHOSiBjOhhEHIhrtzRsdUWQ2LtrmkHK9Q5T6xA.

- McDevitt, Michael, and Patrick Ferrucci. “Populism, Journalism, and the Limits of Reflexivity: The Case of Donald J. Trump.” Taylor & Francis, 20 Oct. 2017, www.researchgate.net/publication/320533962_Populism_Journalism_and_the_Limits_of_Reflexivity_The_case_of_Donald_J_Trump.

- McGuire, Stryker. “Review: The Elements of Journalism by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 29 Nov. 2003, www.theguardian.com/books/2003/nov/29/society.

- McNair, Brian. “After Objectivity? Schudson’s Sociology of Journalism in the Era of Post-Factuality.” Taylor & Francis, 1 Aug. 2017, www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1347893.

- Peron, James. “Political Correctness: A Manufactured Crisis.” Medium, The Radical Center, 25 Jan. 2019, medium.com/the-radical-center/political-correctness-a-manufactured-crisis-3d7dfb38619f.

- Pham, Sherisse. “Germany’s Der Spiegel Says Star Reporter Claas Relotius Wrote Fake Stories ‘on a Grand Scale’.” CNN, Cable News Network, 21 Dec. 2018, www.cnn.com/2018/12/20/media/claas-relotius-spiegel/index.html.

- Wang, Amy B. “’Post-Truth’ Named 2016 Word of the Year by Oxford Dictionaries.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 16 Nov. 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/11/16/post-truth-named-2016-word-of-the-year-by-oxford-dictionaries/?utm_term=.1ff21c2dd9ab.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, Karin. “Media Coverage of Shifting Emotional Regimes: Donald Trump’s Angry Populism.” Media, Culture & Society, vol. 40, no. 5, 2018, pp. 766–778., doi:10.1177/0163443718772190.

- Zelizer, B. (2018). “Resetting journalism in the aftermath of Brexit and Trump.” European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 140–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760318

- “Ethical Journalism.” The New York Times, 5 Jan. 2018, www.nytimes.com/editorial-standards/ethical-journalism.html#.

- “What Is the Purpose of Journalism?” American Press Institute, www.americanpressinstitute.org/journalism-essentials/what-is-journalism/purpose-journalism/.